I've pretty much stopped writing posts exhorting policy makers to engage in deficit-financed fiscal stimulus, not because we no longer need it -- we do -- but because it feels like a waste of time. With the fading of the Recovery Act along with state and local budget cuts, U.S. fiscal policy has turned contractionary (see fiscal drag figure here).

Yes, the economy is getting better, and pretty consistently at that. But it's still a slog, gas prices are pushing the other way, housing remains in the tank (more on that in a later post), joblessness is still highly elevated, with 40% of the unemployed stuck in joblessness for at least six months (before the Great Recession, the average share of the long-term unemployed was about 15%).

But I'm going to briefly drag this critique out of hiding for two reasons. First, there's been a spate of research on the bang from fiscal stimulus when monetary policy is "at the zero lower bound" (ZLB), as it is now (meaning the Federal Reserve is holding the main interest rate they control at about zero in order to stimulate more borrowing and investment). And second, because Europe is providing such a sad, natural experiment of this thesis.

On the first point, the ZLB is important because once the nominal interest rate that the Fed sets -- the Federal Funds rate -- is at zero, they can't take it down further, even if weak growth and high unemployment suggest they should. Brad DeLong and Larry Summers have a new paper that takes 52 pages and lots of Greek letters to prove that fiscal stimulus is particularly helpful in this situation and not particularly costly either (see low interest rates noted above; by the way, if the Greeks could claim royalties on the use of their letters, that could help relieve another big economic problem we currently face).

These dynamics have been known since Keynes but have been forgotten, so good for Brad and Larry, but if Paul Krugman's relentless flogging of the point hasn't broken through, I fear nothing will.

There's been a lot of debate about the magnitude of fiscal multipliers -- how much bang you get for each buck of stimulus -- when interest rates are at the ZLB (a multiplier of 1.5 means $1 of fiscal stimulus returns $1.50 of growth). In normal times, the Feds can raise rates to offset the extra spending, or government borrowing can crowd out private borrowing, but at the zero bound, that's not the case, and that means the fiscal multiplier is larger.

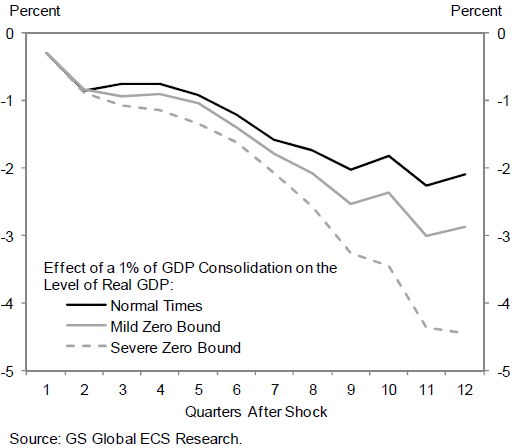

Researchers at Goldman Sachs have some careful new work which derives the magnitude of the multiplier under different degrees of the lower bound. The "mild" case is a ZLB that doesn't last for too long and while the short-term rate is stuck at zero, longer term rates can still come down (which helps to offset the demand contraction). The "severe" case is generally what we've been dealing with in this downturn -- the Fed has the rate at zero and intends to hold it there though 2014! -- and it assumes longer term rates won't fall either (here's where QE comes in -- that's how the Fed targets the longer term rates, so perhaps we're actually somewhere closer to the mild ZLB than we'd be without QE).

The figure, which simulates a 1% of GDP fiscal contraction (so reverse the signs for a stimulus) shows large multipliers after a few years of between 2-4.

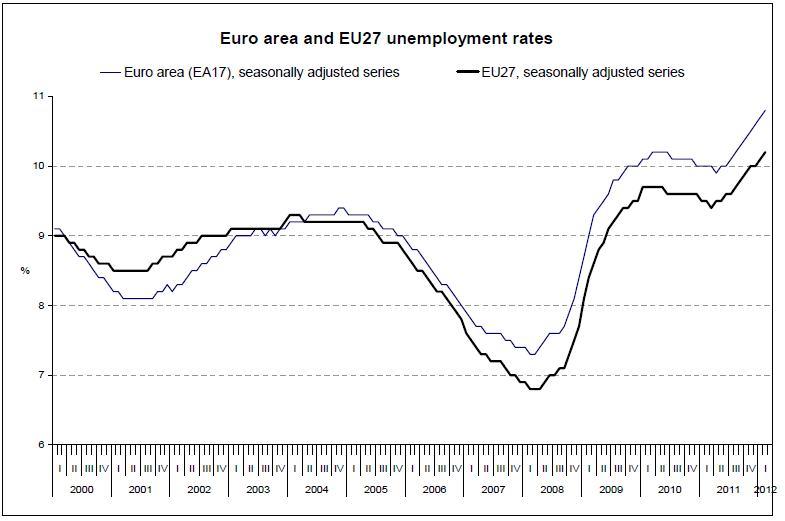

Still not convinced? Then let's turn to the second point... Europe. If the Goldman's findings are ballpark correct, then the UK and EU's fiscal consolidations should be contractionary, recessionary, and inducing of higher unemployment. Voila:

Source: Eurostat

Like I said, on this side of the pond we're busy debating the most austere budget in recent memory -- the one adopted by House Republicans -- and trying to figure out how to stop a planned fiscal train wreck -- consolidation of 3.5% of GDP -- in January of 2013. So all of this is for naught in the current context. The reason I raise it at all is because there's another recession out there somewhere and who knows? Maybe by then we'll be ready to relearn old lessons and get this right next time.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.