In a refreshing break from all the health care mishegoss, I keep running into people who want to talk about this idea that faster inflation would help the economy pull out of its growth slog. Since I view faster growth as an extremely laudable and overlooked goal, allow me to say a bit more about this debate.

Here's my summary of the critiques I'm picking up:

-- faster inflation will just lower real wages and incomes -- how could that possibly be a good thing?

-- the things that faster inflation does right now won't help as much as you think they will.

-- even if it would help, it's a lot harder for the Fed to generate faster price growth than people think.

But first, why go there -- toward higher inflation -- at all? Two reasons, both having to do with the unfortunate ZLB (zero-lower bound): the fact that the main tool of the Federal Reserve, the Fed funds rate (FFR), is stuck at zero. First, since the real rate is the nominal rate minus the inflation rate, at the ZLB, the real rate is the rate of inflation times -1.

Second, and this is less important now, a higher inflation rate in general is insurance against running into that ZLB, as explained by Larry Ball here.

Now, this next part is important. If you use a Taylor rule of thumb to figure out where the FFR should be right now given inflation and unemployment, you get a number around -2 percent. With PCE inflation running at 1.2 percent in the most recent data, that means the effective FFR is still too high.

But if you tweak that calculation is a way that I think you should, i.e., by increasing the measured unemployment rate to reflect its downward bias due to people leaving the labor force because of weak labor demand, then you find that the FFR should be more like -4 percent. No wonder we're stuck in such a slog. (Later, I'll post something showing these calculations.)

So, if any of that is close to correct, shouldn't the Fed be trying to crank up the inflation rate? Well, let's consider those bullets above.

I spoke to the first one the other day -- I do share concerns about slower real wage growth and I'm not so quick to accept the assumption that faster inflation passes through one-for-one to nominal wages, especially for lower wage workers and especially at times of weak labor demand. However, I think the pass-through does at least partially occur and that the benefits of faster growth, more jobs, longer average work week, would outweigh the costs.

On the second point, as Mark Zandi noted to me the other day, while higher inflation helps by reducing the debt burden on those who owe nominal dollars to their creditors, it's a little late for that -- the deleveraging cycle is largely behind us. Zandi also noted, insightfully, I thought, that even if you did lower real labor costs through higher prices, he doubted that would juice much hiring. Labor costs are already awfully low.

But it's the third point that I find most interesting and challenging. There are smart people on opposing sides of this issue of whether the Fed could generate faster inflation, and for reasons both economic and institutional, I think the nay-sayers -- the ones who say the Fed could not drive inflation up very much -- may be right, though I'd probably change "could" to "would."

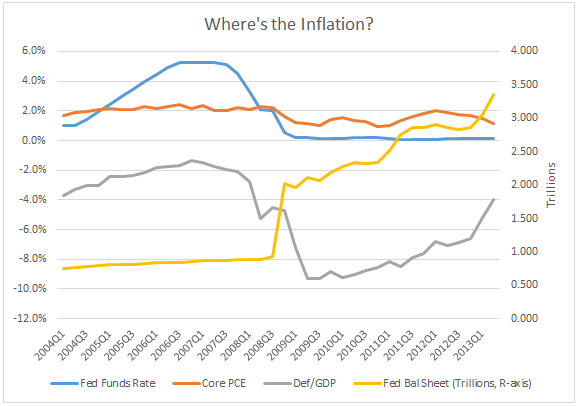

The first thing you want to ask yourself is why haven't their actions thus far done much in this regard? The figure below shows a bunch (too many, I know) of lines relevant to this debate. Ignoring the deficit/GDP ratio for a minute, note that as the FFR went to zero and the balance sheet grew from $1 trillion to $3.5 trillion, inflation (measured by the PCE core deflator) puttered about, and if anything, decelerated most recently as the balance sheet took off.

Sources: Federal Reserve, BEA

There's always the counterfactual and I wouldn't for a moment discount the view that we could easily be looking at deflation absent the Fed's interventions. But at first blush, it's certainly not obvious from this picture that the Fed could drive inflation up much (more careful statistical research comes to a similar conclusion re the impact of the Fed's "unconventional methods" on inflation).

Moreover, there's a strong, hawkish, institution bias against trying to boost the inflation rate in ways suggested by those calling for significantly faster price growth. Bernanke and Yellen have proven themselves to be stalwart warriors in the fight against weak job growth and high unemployment. But they've been equally clear that the reason they're comfortable with aggressive monetary stimulus is that they believe inflationary expectations are "well-anchored."

Larry Ball sensibly points out that if such expectations are well anchored around 2 percent, as they are, then there's no reason they couldn't be just as well moored at 4 percent. But I don't think Ben and Janet et al buy that argument. It's obviously theoretically possible that the Fed could print enough money to gin up more inflation. But it's hard to for me to imagine they would.

Finally, there's the darn Congress. I have argued long and hard that even aggressive monetary policy is rendered far less effective when faced with fiscal headwinds, as you see in the chart (note the rise in the deficit to GDP ratio; that's fiscal drag). I'm sure Bernanke agrees, which is why he used to always be importuning the Congress to help him out with some fiscal tailwinds for which they rewarded him with the opposite.

The point is that this too makes it hard for the Fed to generate more inflation, or for that matter, much more growth. They can set the table with lower rates at both the short and long end of the yield curve, and they've done so. But absent more good, old-fashioned demand from households and companies, there's too few customers sitting down at that table to buy a meal.

All of which leads me to the conclusion of this fascinating (; > {)) discourse: our economy is seriously demand-constrained and while the Fed is doing a lot to help, we're still stuck slogging along (e.g., look at the recent deceleration in the ADP jobs numbers).

Much more needs to be done. Maybe this new budget conference will loosen the knot of sequestration a bit, but that's not what I'm talking about. I actually have what I humbly submit is a strong, pro-job-growth agenda in mind, which I'll be rolling it out shortly, so stay tuned. And no, it won't get anywhere soon (even though it's surprisingly inexpensive), but I'm playing the long game here. It's the only one in town.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.