By: The Alpha Pages

James Pethkoukis was late to the party.

Last month, The Week author modernized a question dating back to economist David Ricardo in 1814 and the Luddites' chief worry about the automatic loom during the Industrial Revolution.

In the article, "Is the internet killing middle class jobs?" Pethkoukis reignites an age-old debate on the role (or non-role) of technology in fueling unemployment.

The author explores a recent Harvard Business Review article by former Intel executive Bill Davidow called: "The Internet Has Been a Colossal Economic Disappointment." Davidow argues the Internet fueled widespread job displacement and spurred underwhelming job creation.

But before Pethokoukis concludes indecisively on the employment impact of disruptive technology or compares the payroll levels of Facebook today versus General Motors in the 1970s, he paints a grisly future where average Americans and the 1% live under extremely divergent conditions.

"The robopocalypse for workers may be inevitable," he opens. "In this vision of the future, super-smart machines will best humans in pretty much every task. A few of us will own the machines, a few will work a bit -- perhaps providing "made by man" artisanal goods -- while the rest will live off a government-provided income." [1]

Today's conversation won't aim to answer Pethkoukis' title question, which recalls a two-century debate and is exhaustingly prone to theoretical over-examination. Because so little mainstream conversation on the capital-labor dynamic of technological waves and global trade exists, few have taken the first step to solving any problem:

Admitting one exists.

Instead, let's move beyond Pethkoukis' hypothetical dystopia, which reads like a bad Matt Damon film, explore solutions in today's broader debate, and make some money in the process.

This Debate is Long in the Tooth

"Does technology kill jobs?"

This question remains locked in a theoretical time warp, with limited discussions about technology's role (or non-role depending on one's stance) in displacing workers.

If the "robot owners" vs. "non-robot owners" or capital/labor chatter sounds Marxist in nature, it's because it falls in the narrative. The "M word" makes both free-market movers foam and liberal academics nervous by association. That doesn't mean the conversation should be ignored.

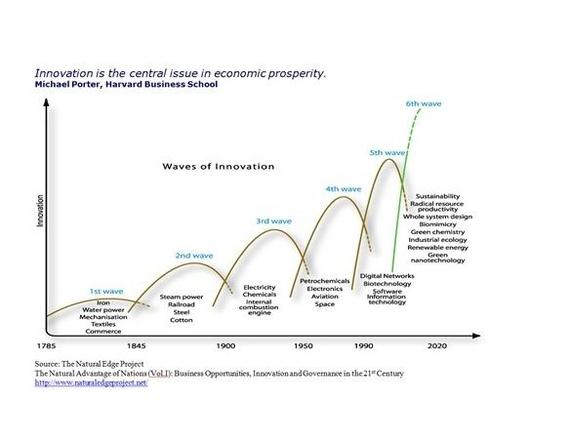

The most recent wave of technological innovation to hit America (the 5th Wave in the graphic below) has dramatically fueled globalization, again realigned the American workforce, and established the base for the next wave of industries and associated jobs.

That hasn't stopped pundits from bickering over consequences without advancing new ideas that address income-level divergence in the new technological era. Economists have offered solutions, some good, some bad, and some that would require turning society on its side.

Like Harry Reid's Senate, It's Still Stalled in Debate

The primary concern for liberal economists appears to suggest that technology adoption increases productivity and societal wealth, but it also produces a widening income gap for those with the greater stake in the implemented technology. That inequality seems to trump innovation.

Have at it, Paul Krugman: "Smart machines may make higher GDP possible, but also reduce the demand for people -- including smart people. So we could be looking at a society that grows ever richer, but in which all the gains in wealth accrue to whoever owns the robots."

As society grows richer thanks to innovation, the pie expands, but the wealthiest tech owners take the largest share. Therefore, it appears that the median income, that middle 50th percentile, will make less money than the average of all Americans due to the skew of the economic distribution favoring the owners of the technology.

Opponents might mock this stance by reciting a childish version of that argument: "Mean technology capitalists will mean falling means for Americans in a nation where mean incomes still rise while median incomes fall."

Some have called for higher taxes on tech companies, investors, and the benefactors of that wealth, which can be redistributed to lower income Americans...who can would again buy the products created by the next generation of technology. Then, those profits will be taxed at a high level, and the circle of theory continues, except they ignore tax havens and capital flight (the latter two being matters that Larry Summers has addressed in his solution to the Robopocalypse).

Then, there's the alternate take: Technological innovation raises society's standard of living, but it comes at the cost of rising income inequality. If a new wave of innovation leads to greater efficiency, a workforce can shift to new skills, career paths, and entrepreneurial endeavors, and jockey for position in the next generation of dynamic wealth caused by technological advancement.

Here's the Bill Maher-ish way of mocking this argument: "Everything will be fine, trust us... we're job creators. What do you mean you don't know how to start a multinational company that has utilized public supply chain infrastructure paid for by taxpayers?"

This crowd loves to point out that America started as a nation of sustenance farmers, but due to substantial innovation, America is now agriculturally self-sustainable while only relying on 1% of its population to feed its people. There was a standard of living boost for all...

Thanks to ag-tech innovation, Americans were able to move into new careers. Cities formed as Americans moved to urban environments. New trades emerged under that 1st Wave of Innovation list above. We saw a boom in commerce, iron production, and mechanization.

The 19th century Luddites' worry about the economization of labor in the textile industry ultimately eased when workers shifted to non-automated sectors. Afterward, the hypothesis of "technological unemployment" was dismissed and dubbed the Luddite fallacy.

Future waves of innovation, and a resulting unequal distribution of the wealth, followed.

With each wave, a conversation about "technological unemployment" continued to evolve.

Two centuries later, the argument over how to handle consequences of each wave, from income distribution to new skills training for the next generation of jobs, is still taking shape, except, of course, on Capitol Hill.

But widespread tech advancement during the past 20 years has been dramatic. Many industries at once have automated or digitized that some 21st century critics' arguments on technological unemployment make today's current joblessness levels ever more difficult to ignore.

New technologies have radically altered many industries. Due to population size, economic factors like housing that anchor workers to local economies, and the incredible consolidation of industry due to computers and the internet to remove double work or to streamline processes, displaced jobs have not been replaced by the "jobs of the future" at an acceptable pace. These are central views by authors and IT engineers Marshall Brain and Martin Ford in their 2009 book The Lights in the Tunnel: Automation, Accelerating Technology and the Economy of the Future.

Some economists have predicted that robots and automation in the future could displace 80% of today's current jobs. That's a horrifying number at first sight, but keep in mind a high percentage of farming jobs were displaced during that first technological wave.

But let's assume that the Robotapocolype is upon us, and current American jobs are going to vanish - hopefully with new industries able to emerge within the decade.

Let's suppose that the truck driver, which is the most popular job in many states, is replaced by self-driving cars thanks to Google's latest experiments.

Let's open up a few ideas on what can be done by companies, policy makers, and investors, and move the debate toward the next step in addressing the fact that nearly 38% of Americans are out of full-time work and middle-class income levels have been stagnant for decades.

Let's have a real discussion about how the hell to approach this situation from a different angle than past policy prescriptions that are rooted in New Deal economics.

What Ideas Won't Work?

Assuming that Davidow is correct about the Internet's lack of job creation, recent proposals to close the wage gap aren't going to stop the Robotcalypse from swallowing the jobs of today.

Ideas to address the negative effects of automation fail to complement initiatives to reduce the growing income gap between the rich and the poor.

For example, to fix the growing wage gap, Berkeley economist Robert Reich has suggested a number of redistributive proposals that President Obama has re-coined as "Middle Class Economics." If anything, these ideas might accelerate the erosion of the middle class as technology replaces human workers due to financial incentives.

Reich proposes plans to raise minimum wages and allow low-wage workers to unionize. This might be a short-term fix in theory, but Reich's solutions only provide incentives for greater technological displacement among low-wage employees.

Vice reported in November that in the U.K. "jobs paying less than £30,000 are nearly five times more likely to be lost to automation than jobs paying over £100,000." The low-wage jobs that are now booming in the service sector, including servers and retail employees, and other positions like administrative support, transportation, and manufacturing are the most susceptible to automation, according to research from Oxford University's Carl Frey and Michael Osborne.

Raising the cost of labor through wage mandates will accelerate the financial argument to replace humans over the long-term (unless you raise the costs of technology, which we'll address soon.)

Reich also proposes a huge public investment in infrastructure. That includes fixing our roads and bridges, boosting Internet infrastructure to improve user access in remote or disadvantaged areas, and improving our power and water systems.

And while that would be a significant one-time Keynesian investment--a throwback to New Deal policy prescriptions--it sets up conditions for an acceleration of job-replacement in the future.

The reason: Public taxpayers would be investing in the very infrastructure on which the corporate robots will operate. (Remember, those trucking jobs are still going away thanks to self-automated supply chains). A broad short-term fix might be politically favorable, but they fail to address the broader labor-capital dynamic of today's technological revolution. It's also a massive economic transfer, again to owners of technology...in this case the shareholders of Caterpillar.

Finally, Reich goes full progressive with an old favorite: raise taxes on the wealthy to pay for all of his plans. That includes making the payroll taxes more progressive and that is the most labor-intensive tax that businesses face (although healthcare costs are catching up). Again, anytime taxes make human capital more expensive, it justifies technological adoption or doing more with fewer workers.

Higher wages through government fiat favor technologies, which are more cost effective, never take days off from work, don't require government-mandated healthcare, and are statistically less prone to error than a human counterpart is.

Why Technology Is Fueling Incredible Wealth...

In today's society, a massive misconception exists about the divide between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of Americans. Most people assume that rich Americans were born into wealth, or that they are simply Wall Street tycoons or the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies.

However, research released last year by Joshua Rauh, a Stanford Graduate School of Business finance professor, and Steven Kaplan, professor of entrepreneurship and finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, note that just a small number of America's wealthiest fall into either of these two categories.

According to their research, the recent wealth surge for the top 1% of the 1% evolved from an ability to invest in or own technology that globally expanded the scale of companies or individuals like movie stars or athletes.

Not only does this suggest technological infrastructure, but also the global expansion of content, services, and product branding. Rauh and Kaplan state that this is a relatively new phenomenon.

In their research, they note that in 1982, the Forbes 400 list of the wealthiest people on earth was dominated by what was deemed "Old Money," which consisted of family names transcending generations of wealth from Old Europe and the Robber Barons or emerging America.

For example: The Vanderbilts, the Rothschilds, and the DuPonts.

But within just 30 years, the top 1% of the 1% have risen from a more recent wave of technological innovations on the global markets. They have expanded businesses to the four corners of the earth through best-in-class distribution of high-quality and often commoditized products.

Rauh and Kaplan explain that on a weighted basis nearly 25% of companies owned by the wealthiest 1% have a sizable technology component enabling them to reach global consumers on an unmatched scale.

Retail companies with strong technology components and expanded scale have made billions for entrepreneurs like Jeffrey Bezos of Amazon and the heirs of Sam Walton of Wal-Mart. In addition, tech giants like Microsoft, Apple, and Cisco have generated billions of dollars for their investors. Their founders sit atop the list of wealthiest human beings.

But there's one thing to note. The Vanderbilts, the Rothschilds, and the Duponts were also families built on Waves of Technological Innovation from previous generations in expanding global sectors like shipping, railroads, chemicals, and international finance. All of these industries can be found in the first, second, and third waves of innovation that swept the globe.

But over time, as new industries expanded scale and implemented new technologies, the Vanderbilts' were rivaled by the Waltons, the Gates, and the Ellisons.

And while each wave created immense wealth for tycoons, it increased the standard of living for billions of people.

This duel phenomenon has created an interesting challenge for the left-of-center who are interested in redistributing wealth or using 20th century policy to address today's joblessness.

That's because when the next wave of innovation emerges, creating remarkable wealth, it also will dramatically improve lives around the world (Imagine how many jobs would be displaced if green energy were able to provide a constant, near zero-cost replacement for oil - and still do so while reducing geopolitical concerns in hotspots around the globe).

This is such an obvious conundrum that Krugman, upon reviewing Rauh and Kaplan's work in December 2012, said that ownership of technology is a far greater driver of economic inequality than thought, and worried about proposed solutions to the associated wealth gap.

Krugman stated: "If this is the wave of the future, it makes nonsense of just about all the conventional wisdom on reducing inequality. Better education won't do much to reduce inequality if the big rewards simply go to those with the most assets. Creating an "opportunity society," or whatever it is the likes of Paul Ryan are selling this week, won't do much if the most important asset you can have in life is, well, a lot of assets inherited from your parents."

So, conventional wisdom must be turned on its side.

Academics, companies, and investors need to recall Abraham Lincoln's second address to Congress. Said Lincoln: "As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew."

There are a wealth of ideas we will explore tomorrow - including an investment philosophy one can use to hedge against the Robopocolypse.

Here Are Potential Solutions to Improving Income Distribution as Disruptive Technology Emerges

In a 1949 article called Why Socialism, Albert Einstein addressed his concerns about impact of technology on employment.

"Technological progress frequently results in more unemployment rather than in an easing of the burden of work for all," he wrote.

Einstein idealistically proposed the establishment of a socialist economy as a solution to dealing with technological unemployment.

Of course, he wouldn't live long enough to see the glorious consequences of socialism in Russia, Cuba, or even Venezuela today. Putting both capital and technology in the hands of government has proved to be a remarkable disaster historically. (The U.S. government spent more than $2 billion on a healthcare website and unrolling of the Affordable Healthcare Act with the grace of a gaggle of drunk clowns falling out a car door.)

Ruling out theory, and aiming toward more market-based approaches, let us explore a number of possibilities that politicians, investors, and entrepreneurs have proposed or might consider in today's world.

1) Expand Opportunities for Crowdfunding and Incentivize Small Business Owners to Provide Employees with Equity

Some modern solutions are underway, and they begin with the way capital is allowed to flow across the economy.

As we examined last week, deregulation of the crowdfunding industry could be a major boon to Americans looking for ways to hedge against job instability. It's not clear that crowdfunding is going to be an immediate solution to the jobs crisis, this will allow new companies to emerge.

For years, only accredited investors - those who earn more than $200,000 each year or maintain a net worth of more than $1,000,000 (excluding their primary residence), or they are entities with more than $5 million in assets - could put their money into venture capital outlets. With the surge in new technologies and digital properties over the last two decades, the richest Americans were able to build incredible wealth due to their ability to tap into the private markets.

Crowdfunding equity might need to go further - offering tax incentives for investors or ensuring the investment of tax credits into existing global technology companies that are ahead of the curve. The primary concern, however, is that private equity companies and angel investors will remain in-demand from startup companies for their leadership, knowledge, and deeper pockets.

It's not earth-changing, and there are downsides, but it's an important first step.

2) Encourage Stock Market Ownership or Broader Capital Onwership

In his 1976 book titled Peoples' Capitalism: The Economics of the Robot Revolution, James Albus argued that the world would be able to expand capital ownership across various classes in a way that would enable everyone to become a capitalist and gain income from their ownership of capital assets.

The idea that more people are able to have shared equity is probably past its time given the immense percentage of wealth owned by a small percentage of Americans.

If the government's goal is to provide Americans with a healthy retirement, the logical stance would be for them to own Google Stock, and not T-bills earning 3% on an annual basis.

For the better part of five years, the top 1% has enjoyed the wondrous Keynesian experimentation of pumping trillions into the stock market. While benefits have been extended to the wealthiest owners of global stocks, the number of Americans who are actually participating in the stock market these days continues to erode.

Boosting confidence in the markets is a critical step toward addressing inequality, and investor education on technological investment is central to expanding the ownership society.

3) Make Human Capital More Affordable:

Income taxes and social security taxes are levies on one thing: Human capital production.

So, Robert Reich's proposals to raise taxes, even on six-figure incomes, will invite more robots.

If anything, taxes on human capital should be reduced to maximize cost value against the cost of implementing automation into a company. For those in favor of replacing that pool of government revenue, they'll likely need to focus on production taxes elsewhere. Capital gains are a likely target, but there may be more incentives to robotize our government agencies.

Progressives might consider alterations to the tax code. Rather than hammering Americans with social security taxes, the IRS calculates the role of technology in each business and tax robots instead of human beings. But altering the tax code isn't enough.

Changing the way employees are compensated is another critical factor. And providing opportunities to unlock new classes of entrepreneurs is more than just teaching creativity and classes on how to start a business. And that brings us to our next factor.

4) Eliminating Excessive Occupational Licensing Regulations

Entreprenuerialism is challenging enough. It's hard to do it with an arm tied behind your back.

There are hundreds of industries in the United States that are burdened by excessive regulatory hoops that mid-tier skilled entrepreneurs must jump through in order to start their own business.

And many of these entrepreneurs want to operate in industries that require very little automation or threat from robotics.

For example, these industries include interior design, hair-dressing, beauty treatment and other operations that tend to require small workforces, but face immensely complex layers of bureaucracy to get started.

This tends to be a local and state problem, but the Federal government every now and then creates burdensome regulations through their laundry list of Alphabet Soup agencies that make it virtually impossible for entrepreneurs to get their dreams off the ground.

5) A Basic Income For All

This isn't popular among the well-moneyed crowds and it's often referred to as a socialist concept.

However, the ability to streamline the dozens of entitlement programs and ensure that consumer spending remains well-oiled are the primary arguments. The Universal Basic Income in many ways is a tonic to save market capitalism, ensuring a constant injection of capital cycling through the markets. The first massive bailout was for the banks. The next one might be coming to address a massive economic gap that makes it harder for people to afford the goods and services being curated by robotics in the first place.

The technology owners still will make an immense amount of money.

Other variations of the type of system include a shift to a four-day work week, or the possibility of two workers sharing the same role. This has been proposed by technology owner Larry Page of Google as a way to provide ways for more people to gain employment.

However, it's unclear how well-paid these employees would be and what sort of career path each might enjoy in the future due to less responsibility and fewer hours.

Perhaps the compromise can be found if taxes are reduced if through more streamlined efforts, taxpayers are able to...

6) Cut Out the Middle Man?

Should the rise of robots fuel the elimination of millions of jobs, and that's an assumption we're making, the solution surely is not more government administrators harvesting more tax dollars or politicians having backroom deals to create loopholes for corporate backers.

Anyone who is a proponent of redistribution of limited wealth or should be more anarchic than totalitarian in nature. Tax reform that reduces the beast of Washington spending is critical.

Today, 15 cents of every dollar that goes to Washington stays within 100 miles of the town. That has made Washington so utterly disconnected, as five of the six richest counties in America surround the D.C. area.

That would warrant greater transmission of supposed government payments directly to shareholders from robot-owning companies, and not sending that money to government where a bureaucrat can skim their share off the top.

But good luck getting anyone to get anyone who loves to tax and spend from allowing companies from identifying ways to make that ever work.

Unless we begin to debate new approaches and begin to think beyond the typical two- or four-year election cycles, we'll truly only be left to one solution.

And only Washington will be to blame when this strategy is all that remains.

7) Leave Every Man for Himself (and give them investment insight)

Technological advancements are happening faster than new sectors can emerge, train and hire workers, and show remarkable profitability. The robotics industry might create a million jobs, which looks great on paper, until we see the squeeze of lower-tier workers replaced.

With luck, these workers will benefit from a liberalization of the trades industry, deregulation in the service industries, a boost in crowdfunding entrepreneurialism, and a greater emphasis on local economies.

Furthermore, those "jobs of tomorrow" that politicians love to discuss so often, are going to rely further on technology and the consolidation of the industries of yesteryear.

Investors (and Americans whose jobs are threatened by robots) are therefore better off looking for ways to hedge their finances by examining six ways to invest in radical changes in technology. This is a simple guide to understanding not only how to invest in innovation, but what innovation truly looks like across multiple waves of history.

Investors should start looking at these opportunities:

- Invest in the robots that can accelerate trade and expedite the transfer of goods or services. Each day, more than 100,000 flights take to the sky, sending cargo and passengers around earth. But we still rely on aviation technology from the 1960s to do so. Opportunity exists for companies that can improve logistics at any point in the supply chain, particularly with the growth of sensor technologies. If you can build it or ship it faster, reduce service and travel time, you have an advantage and a profitable hedge. This is desirable on the widest scale possible.

- Invest in companies that improve the speed of information flow, transfer of capital, or methods of conversation. Information moves at the speed of light, and technology has been critical to maximizing communication across the world. But investing in companies that stand most to profit from the transfer of information and capital (see PayPal/Twitter/Facebook), you'll be able to hedge against the fact that future employees will be required to do so in the future.

- As it becomes more difficult to increase speed and delivery efficiency, a natural focus for robotics and technology implementation is cost efficiency -- using fewer resources, while expanding size and scale. One of the central costs is naturally the electricity used to power gadgets across a supply chain. Alternative energy investment is a formidable investment opportunity as it challenges more conventional resources to the point of grid parity. Energy processes that are capable of utilizing less fresh water at a time when water costs may spike in certain areas of the United States is also a bleeding edge investment arena.

- Invest in innovations that have the power to harness previous innovations to maximize profitability. A classic example is the iPod and the MP3 player. The former was immensely successful because of the introduction of another sales innovation, the digital Apple Store, which vastly changed the future of the online global marketplace. Collaboration in vertical integration of technologies is also a prime investment.

- Finally, an often the most over-ignored, invest in universally adoptable innovation. Remember, innovations bypass cultural barriers such as common language, religion, or political ideology. Everyone in the world wants or needs a phone, food, and housing. Many companies that aim to solve the most basic problems in the world - food, water, energy, communication, health, and technology - and own the technology that will continue to fuel the world long after the next wave follows.

This Article Originally Ran in The Alpha Pages on May 5.