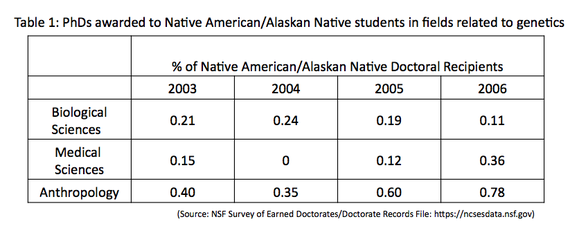

We have a diversity problem in the field of human genetics. Less than 1 percent of the Ph.D.s in fields related to human genetic research go to Native Americans (Table 1), and, according to Dr. Kim Tallbear of the University of Texas, they make up less than one fifth of 1 percent of the members of the American Society of Human Genetics. This is particularly troubling in light of a history of exploitative genetics research with Native American communities (McInnes 2011). Dr. Tallbear notes, "In many aspects we govern through science. If tribal communities don't have people trained in genetics, we don't have the ability to engage in meaningful conversation with geneticists." Professor Nanibaa' Garrison of Vanderbilt University added:

Native Americans are underrepresented in genetics and genomics research studies. Some reasons stem from historical distrust of the medical doctors and researchers; distrust may stem from poor communication, lack of return of aggregate results or broad study findings, and misrepresentation of the tribe or community.

Scientists must address this problem. One critical step is for researchers to seek community participation in every step of the project -- from initial design to the interpretation of results -- and look for tangible benefits to return to the community. But genetics fundamentally needs a greater diversity of backgrounds and perspectives. This is the intention of the NIH Minority Action Plan and the Native American Cancer Initiative's "Genetic Education for Native Americans" workshops.

This past summer I participated in another initiative: the Summer Internship for Native Americans in Genomics (SING). Organized by researchers and advocates, this annual program aims to teach genomics concepts, equip participants with tools to help their communities make informed decisions about genetic research, and provide them with mentorship opportunities and networking with other Native American researchers and students. "A primary goal of SING is to facilitate the next generation of Native American researchers who can use genomics as a tool to address questions of interest to their community without having to rely on outsiders," says Professor Ripan S. Malhi of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

The SING students I spoke with during the workshop emphasized to me that barriers to participation in science are not always visible to even the most well-meaning professors. Indigenous students pursuing education in the sciences find it difficult to access resources and mentors, and the experience can be very isolating. Holly, a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, described her experiences at Vanderbilt:

I didn't feel like I could completely share my perspectives with my classmates, and I was learning and doing things that no one in my family had done before, so I felt like I was betraying them in some way by creating my own path. ... I spent three years of college feeling like my voice and my perspective weren't important, because it's easy to feel invisible when your chunk of the pie chart is less than one half of 1 percent.

Georgina, a Native American undergraduate studying genetics at Stanford, agrees:

I have always feared social rejection: not being accepted by my family, who calls me a "sidewalk Injun"; being perceived as an artifact by my professors and peers; viewed as a token minority to my friends. ... All of us, Indigenous or not, become who we are as a result of and despite our circumstances. Because my circumstances are different from someone else's does not make them any more or less valid.

SING participants put a great deal of thought into what researchers need to do in order to improve working relationships with Native communities. Holly noted:

I don't remember being afraid of researchers while I was growing up, but I think it was more of an "ignorance is bliss" scenario, because we didn't know about the potential for harm. My family never participated in any research, but I don't think we would have said no. I think it was important for me to learn about the ugly side of research, because a lot of damage can be done when you give part of your body to someone who might not believe that it is sacred. I think it is important for us to learn about the history of abuse and the potential for harm so that we can be well-informed and cautious. On the flip side, I also learned about cases of ethical, really positive research that is being conducted with Native Americans while I was at SING. So I also think Native peoples should understand that not all research is bad, good collaborations do exist, and we may still stand to benefit from some types of genetic research if it is conducted well, with our best interests in mind.

In addition to working to improve healthcare access for people on reservations, Georgina plans to use her education to help her community develop guidelines for participation in genetics research:

It is important that any research is done ethically. Learning, knowing, and respecting cultural lines and avoiding social stigma is essential to ethical research in any community. There are great practices in place; unfortunately, not all researchers choose to follow them. Genetic research and even gene-based medicine could be extraordinarily helpful and could save/better lives, but if it is done in a way that takes advantage of any person or group, it is not worth it.

To conduct research in a more sensitive and ethical way, geneticists need to improve their consultation and collaboration efforts with communities. But lasting change will only come about through the education of a new generation of researchers. As I discovered from my experiences at SING, in this arena geneticists have as much to learn as they do to teach.

References and further reading:

To learn more about the Summer Internship for Native Americans in Genomics, visit http://conferences.igb.illinois.edu/sing/

Bitsóí (Diné), LeManuel "Lee," "Enhancing genomic research through a Native lens," American Indian and Alaska Native Genetics Resource Center.

Schroeder, K.B., R.S. Malhi, and D.G. Smith. "Opinion: Native American Participation in Genetic Research." Evolutionary Anthropology 13.3 (2006): 88-92.

Tallbear, Kim. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press (2013).