From the bowels of the Budapest Metro, the steps at Határ Street lead out into an industrial wasteland sprawling along the highway towards the airport. People huddle about the bus stop and the nearby grey, Soviet-style kiosks. A woman tucks in her child with a felt blanket as the greasy aroma of freshly fried "lángos", a deep-fried doughy bread topped with sour cream, cuts through the chill, promising a sliver of warmth from the fogged window by the metro exit.

It takes less than 20 minutes to reach Határ Street from the city centre by metro. It feels surreal that such a short trip down the line can bring me back to the post-communist years of my 1990s Hungarian childhood. Tourists seldom come here, and why would they? It seems that the only landmark of use is the bus to the airport, one metro stop along at the end of the line -- but that is not entirely true.

I take the path down Határ Street and walk against the wind. The windows of grey apartment blocks to one side reflect the nearby TV tower, and the clues to Hungary's capitalist present glint in the neon lights of the giant Spar supermarket blinking in the distance. At this point, I doubt my own map-reading skills and the GPS of my phone.

The concrete blocks fade into the background after I cross an overgrown railway track, and even with Spar just across the road, the dried leaves to my left trace a path towards country houses typically found in the villages, leading to one of Budapest's hidden treasures.

On first impressions the Wekerle Estate seems like an ordinary neighborhood in Hungarian suburbia; one to two story houses, firewood gathered in the back yards and the occasional barking dog. A man walks his daughter down Pannónia Street away from the urban fragments of Határ Street, fading into the distance between the shuttered houses, flaking pastel façades and the vegetation-laced pathways carpeted with rusty leaves.

Photo Credit: Jennifer Walker

There is no need for the map anymore. I am in the right place. Now all I need to do is to follow the path. All roads of the Estate converge in Károly Kós Square, a green respite at the centre of this "Garden City" surrounded by examples of Transylvanian architecture married with Hungarian Secession.

The midday church bells from the "Munkás Szent József" church (St. Joseph the Worker) echo across the turrets and tiled roofs of the whitewashed buildings and arched gateways. A policeman takes his little terrier for a walk on his lunch break, accompanied by the sound of children's laughter.

On a Sundays, the park at the heart of Károly Kos Square fills with the noise of children running around in the playgrounds. The elderly stroll along the graveled paths as joggers bypass them before going for a stretch in the pagoda trimmed with wrought-iron detail.

Photo Credit: Jennifer Walker

The Wekerle Estate is a community in its own right, and even though it's set inside Budapest's XIX District, the Estate itself resembles a village in the city, which is precisely the intent behind this avant-garde urban development dating 100-years back.

The architects embraced the philosophy of the Garden City movement that swept through Europe at the cusp of the 19th and 20th centuries, where the housing problem for local workers and clerks motivated the construction of the Estate.

The Wekerle Estate began life attached to a manifesto, designed to be a self-contained, independent urban commune complete with its own churches, schools, even stretching to a cinema and a police station. Its philosophical concept has been swallowed by the expansion of the city over the decades, but the vision of young architects Károly Kós and Dezső Zrumeczky gave the place its own life. Beginning the project in 1908, through the angled rooftops and wooden gables, Kós and Zrumeczky recreated a slice of Hungarian and Transylvanian rural life in the city.

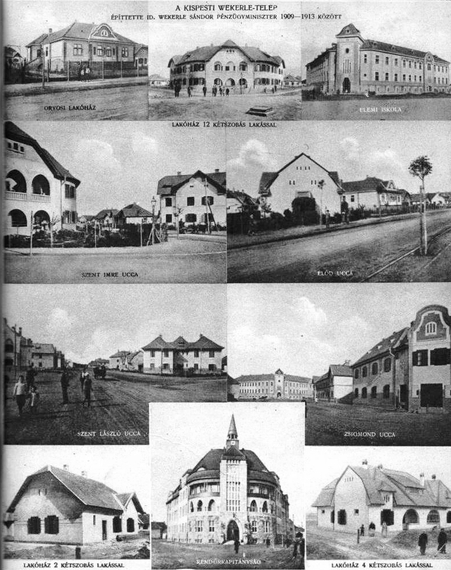

This Image is Public Domain

However, the shadow of the oncoming Great Depression forced construction to stop in 1925. Even though the development was abandoned, the Wekerle Estate was left with around 1000 houses, over 4400 apartments in total, dotting its spider-web street layout. People flocked to this new housing utopia, although government employees were given preference as applicants. In its heyday, young, unmarried clerks and low-level officials filled the neighborhood as its renters.

Károly Kós Square became the heart and the conceptual symbol of the community itself. Its chief architect, Transylvanian-born Hungarian Károly Kós, who was also responsible for the Estate's radial layout, primarily designed the construction of the square.

The rustle of the trees shedding their last leaves along the spacious avenues echo the Wekerle Estate's Garden City origins. Back in the early 20th century, the entire Estate even had its own gardening service. The community gardeners were in charge of maintaining the plants, flowers and trees in all the public spaces, but they also branched out to help with the gardens of many of the private residences.

Photo Credit: Jennifer Walker

The Garden City concept, by combining urban living with home-grown botany, helped its residents to pay the rent back in 1917. Each apartment had its own fruit tree, and the crop for redcurrant was so rich that renters could earn four years' worth of rent by selling their crop.

Even today, the area is a popular place to live. Its residents respect the Estate's history, its green space and 100-year-old trees. Even passing through as a stranger, I sense the strength in the community, as locals greet each other in the street as I pass by.

I step into the small Cukrászda, a café serving cakes, for a coffee. I pay half what I would in even the cheapest downtown cafés of the city. Its nutty aroma and creamy foam, accented with cinnamon, rival some of its downtown contenders.

Photo Credit: Jennifer Walker

The sun illuminates the square and I sit back and watch the children playing through the window of the warm café. For them, it's just an ordinary Sunday, but for me, it's more.