In response to my last post, many readers have voiced concerns over judicial review and what limits should exist, if any. Some have argued that it is an essential process that every law go through to ensure the Constitution is respected. Others, including myself, believe review should be used only as a last resort.

There is no doubt that it is a difficult question. Without an independent judiciary that can review legislation, power becomes to centralized and there is less accountability. However, if the power of courts becomes too broad, nine unelected individuals would themselves determine the laws we live by, something Thomas Jefferson likened to an "oligarchy."

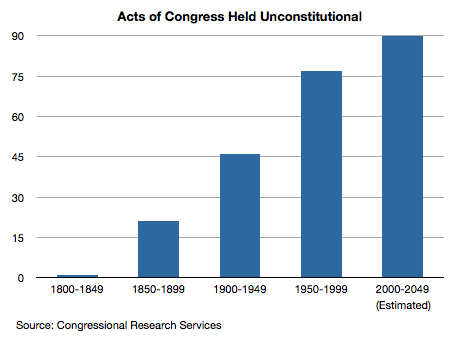

The answer, I believe, lies somewhere in the middle ground, something the president and attorney general describe as "restraint." As mentioned in my last piece, only 163 laws have been struck down since 1803, when judicial review was established. An even closer look at those numbers gives us a crucial insight into the intention of the practice, as well as the complete misinterpretation that is currently in full force:

Over each 50-year period since judicial review was established, the amount of laws held unconstitutional has drastically increased. Since 1999, 22 laws have been held unconstitutional, which matches the total for the entire 19th century. Moreover, the Supreme Court now strikes down a law every half-a-year, up from one every 50 years when judicial review began.

Clearly, the interpretation of judicial review has widened significantly, which is exactly what Jefferson warned against. At its creation, judicial review was clearly intended to be a practice used only when it was tremendously necessary -- that is why it was only used once in the first 50 years of its existence.

No one doubts that the power exists to void laws the court deems unconstitutional -- that is exactly what Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in Marbury v. Madison. But it is fair to question the purpose of such a process, and whether such a broad interpretation works to strengthen or weaken our democracy.

As it is, members of Congress take an oath to defend the Constitution, and the assumption is that they would never pass a law at odds with our founding document. Sure, it happens on very rare occasions. But is it reasonable -- or, frankly, necessary -- to test such an extraordinary amount of laws passed by a democratically elected Congress?

History says no. Judicial review is something the court ought to hold in its back pocket, only to be pulled out when a clear threat to our nation's integrity occurs. It is not, and was never intended to be, a litmus test for every piece of legislation. That's why John Marshall, the father of judicial review as we know it, only once called on his precious creation.