Two Nigerian girls waiting for their malaria test results.

Two Nigerian girls waiting for their malaria test results.

There were so many burned patients I even had to help cut off patients clothes, try to secure IV lines, and help patch burns all while trying to stomach the constant screams and distinct fragrance of burnt flesh.

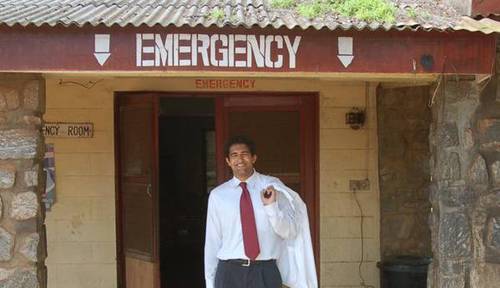

I recently had the pleasure to meet a dynamic Indian-American professional couple at the Indian Consulate on the Upper East Side of New York City. They are both physicians. As intriguing as they were, however, I was especially fascinated with their son, Ravi Parikh. A medical student studying at Vanderbilt, he has just returned from two months in Ogbomoso, Nigeria, studying malaria at the Baptist Medical Centre there.  Medical student Ravi Parikh at a Nigerian emergency room.

Medical student Ravi Parikh at a Nigerian emergency room.

I spoke at length with Ravi about his experiences there. He is still sorting through his many experiences. He worked in the emergency room during a preventable disaster where many were badly burned. And he now believes the most common malaria test in Nigeria is wrong more often than it is right -- and he brought home hard data to support that opinion.  Ravi (center) with the staff of the Baptist Medical Centre in Ogbomoso.

Ravi (center) with the staff of the Baptist Medical Centre in Ogbomoso.

Ravi experienced life, death, and all of the developing world struggles between rich and poor. "Seeing a country with so much potential from natural resources suffering such a complete infrastructure breakdown was hard for me to understand at first," Ravi told me. "This breakdown leads to a massive brain-drain of physicians to the U.S. Doctors there have to work in conditions in conditions where there is often no electricity. So they give up and come here. "The emergency room at our hospital -- which is over 100 years old -- is regarded as one of the best in delivering primary medical and primary surgical care in Nigeria. Yet often it does not have any power at night," Ravi said.  Raining season creates malaria breeding grounds.

Raining season creates malaria breeding grounds.

Nigeria has little government support for healthcare and the insurance industry there is small. But hospitals there, like here, need to pay their bills. Some form of payment is required before most help is rendered -- even in the E.R. "The best part of my project," Ravi said, "was that many of the physicians there were happy to have me conducting my project because my research provided a free service to the Nigerian patients. The results would be useful not only to me but to the Nigerian medical people on the ground," he told me. Ravi continues:

One memorable patient was a man who was misdiagnosed with malaria by two different hospitals and took treatment before I arrived. He presented at the ER again and I enrolled him as a suspected malaria case and we found out that his smear was negative. Upon seeing this, the physician knew he must have advanced typhoid and the man was rushed into the O.R. for an exploratory laporotomy. In the surgery, it was found that his infection led to his intestine perforating. He will have a long and hard recovery process -- but luckily, he is now alive.

Ravi was struck that resources and equipment are simply unavailable in many remote areas of Nigeria. "But the biggest issue for patients in Nigeria is that they have to pay for all their services with virtually no insurance industry and little government support. I am convinced that finding cost-effective solutions to treating these patients is the most worthwhile service to them," he said.  Local living conditions often led to malaria transmission.

Local living conditions often led to malaria transmission.

However, Ravi's life was more affected by another experience than perhaps he yet realizes:

Poverty and maldistribution of wealth (i.e., oil money) is such a problem that one night an oil tanker tipped over and spilled. Many poor locals went to collect some oil worth no more than a few dollars considering the quantity of oil one could collect and carry. Unfortunately, the spilled oil ignited and caused a massive explosion causing a flood of patients with 30 to 80% burns to their body. I was on duty when they flooded the E.R. There were so many patients I even had to help cut off patients clothes, try to secure IV lines, and patch their burns all while trying to stomach the constant screams and the distinct fragrance of burnt flesh. That night will always stay with me and seems relevant to the crazy political situation between the oil companies, armed rebels, and the Nigerian government over oil rights in the Niger Delta. Maybe if the people on the street got some of the country's oil revenues, they wouldn't have had to risk their lives and die for a few dollars of their nation's largest export.

Such thinking led me to leave Wall Street, when I juxtaposed the children I was meeting in the garbage dumps of Indonesia with the high net worth individuals my firm was serving. I thought the children were more deserving of my attention. Ravi's thinking is changing quickly as well. However, malaria was what brought Ravi to Nigeria and it stayed on his mind. In most of Africa where malaria is endemic, he told me, patients are most often clinically diagnosed with malaria and then treated with anti-malarials when they have the nonspecific symptoms such as fever, body ache, and malaise.  Baptist Medical Centre compound, Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

Baptist Medical Centre compound, Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

"Often times, people do not have the resources to pay for a blood smear -- the test to determine if they actually have malaria," Ravi told me. "We tested about 300 patients with the clinical diagnosis of malaria. We wanted to see if it would be cheaper to treat all the patients suspected of malaria -- or test everyone and just treat those with positive Giemsa thick blood smears (the 'gold standard' test).  Some things in Ogbomosho have hardly changed in 50 years.

Some things in Ogbomosho have hardly changed in 50 years.

186 patients tested negative for malaria (123 adults and 63 pediatric patients), while 113 tested positive (45 adults and 68 pediatric). Although most people tested negative, it was still cheaper to treat every suspected case than to test each patient and only treat those who tested positive in each scenario. This study shows that it is more cost-effective in resource poor settings to treat everyone. The con of this approach is over-treatment resulting in resistance. The benefits of treating everyone, along with being more cost-effective, is that over-treating errs on the side of caution potentially save the lives of many children -- most of whom tested positive in my study. Another aspect of the study was to assess the current blood smear technique used in the hospital we worked at -- Baptist Medical Centre Ogbomoso -- uses the Leishman thin smear as does much of Nigeria in low-resource settings. The Leishman thin blood smear is routinely used as blood test to determine the different amounts of white blood cells (immune cells that fight infection) in one's body by viewing the stained and smeared blood under a microscope. To conserve resources the same smear is also used to determine the presence of malaria parasites in the patient's blood. All of the patients received blood smears with both Giemsa (gold standard test) and Leishman stains (currently used in much of Nigeria for convenience). I found that the Leishman smear was only about 45.13% as sensitive as the Giemsa smear. I also then found that the cost of materials necessary for performing the thick Giemsa smear (better test) is actually slightly cheaper, 45.53 Naira (30 cents), than the Leishman thin smear, which costs 49.49 Naira (33 cents). Thus the test is cheaper and much more accurate, the only drawback is the Giemsa smear will take an extra five minutes for more than twice as accurate results.

Ravi's parents -- one an allergist (dad, Sudhir Parikh), the other an anesthesiologist (mom, Sudha) -- told me they were proud of their son. At the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine he is a Canby Robinson Scholar, a distinction awarded on the basis of "demonstrated leadership and scholarship activities." Standing in the Indian Consulate Ballroom, surrounded by more than one hundred other Indian-American professionals, I had the feeling that Ravi was a cut above the rest. I look forward to following his career.

Ravi Parikh is interested in feedback and may be reached directly by e-mail.