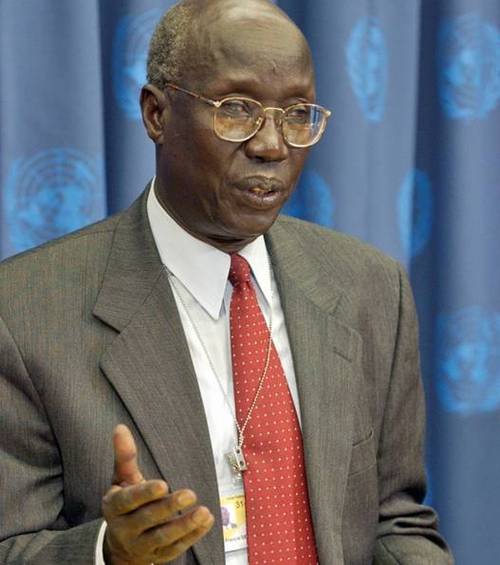

Last year, I met a Sudanese diplomat who was so interesting that I have not been able to get him out of my head - his name is Francis M. Deng.

He is the U.N. Secretary General's Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide at the level of Under-Secretary-General.

I was introduced to Francis at a cocktail party honoring H.E. Father Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann, the U.N. General Assembly President. Peter Yarrow, of Peter, Paul and Mary, had invited me as his guest to this event.

I met recently with Francis at his office overlooking the busy traffic of the F.D.R. highway below to discuss how he is handling such a weighty responsibility. As the U.N. Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, Francis' job is to alert the world of situations in a particular country or region that could potentially result in genocide, and make recommendations for preventing or halting the bloodshed. He acts as a catalyst of action within the U.N. system and, broadly speaking, within the international community. Francis believes -- based on his many years as a diplomat and thought leader at various institutions -- that genocide is almost always a result of national, racial, religious, and ethnic identity-related conflicts. As such, it can be anticipated and even stopped before it begins by understanding these underlying causes. The conflict does not result in the mere differences but in the inequities discrimination, marginalization, and exclusion associated with those differences. Identity-related conflicts ultimately become a clash between those who "belong" and those who have been excluded and marginalized to a point of near statelessness. Francis acquired global insights into these identity issues when he was Representative of the U.N. Secretary-General on Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) from 1992 to 2004. During his missions to the affected countries, after meeting with national leaders and government authorities at various levels, he would then meet with the displaced and traumatized persons.

As he left, he would ask them: "What message do you want me to bring to your Government leaders?" The response was often, "Those are not our leaders!" Government authorities identified these tragic victims with the rebels and saw them as part of the enemy. Francis feels he must be able to diagnose the disease before he can proffer a cure. Inevitably, this includes managing diversities and trying to create shared national identities. He attempts to work with all sides of a conflict to build a framework which establishes basic equalities. He is well-educated - to say the least! He holds a LL.B degree from Khartoum University in the Sudan, and both a LL.M and J.S.D. (Doctor of Juridical Science) from Yale University. He also attended London University. He has been frequently recruited as an expert researcher, teacher, and "thinker" at many prestigious institutions. These include Yale Law School, Columbia Law School, New York University, the U.S. Institute of Peace, the Center for International Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies as well as the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, the Kluge Center for Scholars of the Library of Congress, the Woodrow Wilson International Center, and The Brookings Institution. Francis has served as the Ambassador of Sudan to Canada, Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the United States, and as Sudan's Minister of State for Foreign Affairs. He has authored and edited over 30 books in the fields of law, conflict resolution, internal displacement, human rights, anthropology, folklore, history, and politics and has written two novels on the theme of national identity crisis in his native country of the Sudan. He wrote The Man Called Deng Majok: A Biography of Power, Polygyny, and Change (Yale University Press, 1986) about his father, the renowned Paramount Chief of the Ngok Dinka in the Sudan, which Francis was kind enough to autograph for me.

Francis' father had over 200 wives and thus Francis has over 1,000 siblings - that fact alone is sure to grab one's attention. He was appointed to the full-time position of Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide by U.N. Secretary-General H.E. Mr. Ban Ki-moon in 2007, as part of a continuing effort to strengthen the U.N.'s role in genocide prevention. The Advisory Committee on the Prevention of Genocide, which provides guidance and support to the Special Adviser's work, includes:

David Hamburg as Chairman. President Emeritus of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, who has played a pioneering role in the prevention of genocide and deadly conflicts,

Sadako Ogata of Japan, former U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees,

Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize,

General Romeo Dallaire, whose heroic attempt to stop the Rwanda genocide was constrained by the limitations on his U.N. mandate,

Monica Andersson of the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs which had been instrumental in promoting U.N. action on genocide prevention,

Zakari Ibrahim of Nigeria, a former Senior Government Official,

Roberto Garreton of Chile, former Special Rapporteur on Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo DRC),

Juan Mendez of Argentina, Francis' predecessor as Special Adviser, and

Gareth Evans, former Foreign Minister of Australia, who has been a leader in the development and promotion of the emerging norm of the Responsibility to Protect.

Francis and his colleagues at the Brookings Institution's Africa Project developed the concept of Sovereignty as Responsibility which guided his work on IDPs and which has now been widely acknowledged to have contributed to the evolution of the 'Responsibility to Protect.'

When it comes to his current work, Francis believes strongly in two principles:

One, that the diplomacy needed to stop genocide is to a significant degree an art, not entirely a science. While Conflict Resolution Studies are a good foundation, the cultural milieu is so complex that academic expressions are not enough. Like an artist, technical skills only go so far. One must have the touch, culturally nourished. A major aspect of Francis' intellectual work has been devoted to cultivating cross-cultural perspectives on matters that are relevant at local and global levels.

Two, that national sovereignty is key. Governments must manage their own affairs and protect their own people. They may need international support to discharge their national responsibility. When they cannot, international bodies must be ready and able to respond to the crises. This is the essence of the three pillars of both "Sovereignty as Responsibility" and "the Responsibility to Protect."

The U.N. genocide prevention system is straightforward. The Office of the Special Adviser has developed three clusters of countries:

Those on the brink of disaster or actively engaged in genocidal conflicts are coded red.

Yellow indicates that problems exist but have not yet passed the tipping point into genocide.

Green - you are essentially in North America, Europe, and most of East Asia, not genocide or genocide-risk regions.

However, Francis emphasizes that since diversity and disparity are widespread, the potential for genocide is equally global, even though some countries and regions are more vulnerable than others. Francis is not quick to name the red team, as he must have the ability to work with them in order to shift them to yellow and green.

"I am sometimes asked to 'name and shame,' but such tactics make it difficult to move toward resolution and reconciliation," Francis admits. He believes that constructive engagement based on exploring a common ground promises better results than confrontation. He admits, however, that there is room for different complementary approaches. Going on the offensive against a government might preclude Francis from travel to that country and thus hinder his ability to negotiate with the government - or see the actual conditions. Some independent human rights experts have angered governments so much that they are not allowed to visit the countries concerned. They have written their reports from outside the country, using sources that governments then feel justified to discredit since the expert does not have first-hand information.

As the U.N. Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, Francis' role is to call attention to crises. His voice is not needed in regions where the big international players are already involved although his silence in such situations is also untenable. His job is mainly to shine a light into the darkest corners of humanity, not where there is light already. "Genocide" itself is an emotive term that has both legal and popular definitions. Francis is not the arbitrator of what genocide is or is not.

He simply advises the U.N. Secretary-General on specific problems that could erupt into genocide and possible solutions to those problems. Francis is torn between three constituents, each of whom have different objectives and concerns:

Foreign governments, who do not want him interfering with their sovereignty;

His colleagues at the U.N. for whom the label "genocide" creates an accusation that often makes their work on the ground more difficult; and finally,

NGOs many of whom often focus on issues of human rights in a rather adversarial manner.

Human beings are normally harmonious in their relations, Francis believes. Conflicts -- caused by national, racial, religious, and ethnic clashes -- are the negation of human cooperation and peaceful coexistence in its natural state. Francis feels he has a call of duty to help communities return to this natural state of harmony.

Like the city traffic below our window, Francis points out that the cars flow in cooperation, not conflict. When a car -- or an individual or groups of individuals -- go against the traffic rules, conflict ensues. As traffic cop to the world, Francis M. Deng is a thought leader and global citizen extraordinaire. I am confident that if there is one man who can identify and stop genocide before it occurs, it is he.

Edited by LiLing Choo.