Co-authored by Dereck Hough and Corey Stewart

Right now, our nation's capital is experiencing unprecedented growth. While this development has allowed DC to prosper, it has not been equitable. Currently, more than 7,300 individuals live without homes in the District of Columbia -- 40 percent of which are families. We have seen a 50 percent increase in family homelessness thanks to lack of housing options for the most vulnerable. Nationally, Secretary Julian Castro has described this an "affordable housing crisis"; one in which 7.7 million American households pay more than half of their income on rent without any assistance from the government.

Thanks to an impact grant from Georgetown University we were privileged to dig deeper into the real housing crisis in the nation's Capital. We have met with federal officials, municipal officials, non profit developers, formerly homeless residents, professors, and community organizers. This is a three part series revealing how policies or practices act as band aids in the effort to redress the current housing crisis.

While working three jobs to support herself and her daughters, Sasha had difficulty coming up with rent in a city where prices were rising exponentially. The seasonal nature of her jobs and transportation costs made it that much more difficult to make ends meet. To provide for her daughters, she applied for public housing and did not receive a call back until three years later. Today, Sasha -- a formerly homeless mother and woman of color -- lives with her two children in an apartment in the DC area.

Her story is like that of many struggling DC residents. She works tirelessly to provide for her two kids, yet over half of her income goes towards paying rent. She walks a city littered with zip tied banners on chain link fences championing the development of all new "coming soon" affordable housing residences. Why, then, do so many residents like Sasha, commonly distinguished as our city's most vulnerable, struggle to find an affordable place to live? What we found true in the District speaks to a national problem. Public-private affordable housing development subsidizes rising rents for a struggling middle class, but does little to house our nation's poorest residents.

The rate of gentrification in Washington is second among all American cities. While great for city development and economic growth, gentrification almost always leaves in its wake displaced, underserved residents. Take for example Temple Courts, a public housing project torn down in 2008 as part of revitalization efforts of the now bustling NoMa neighborhood. Former Mayor Adrian Fenty promised nearly 600 new affordable units for the displaced families. Seven years later, the property functions as a parking lot for nearby businesses. Even if built, many residents like Sasha will never qualify for residency in these new "affordable" buildings simply because they are too poor -- too poor for affordability. It's policies like this that have allowed for DC's homeless population to increase by 73 percent.

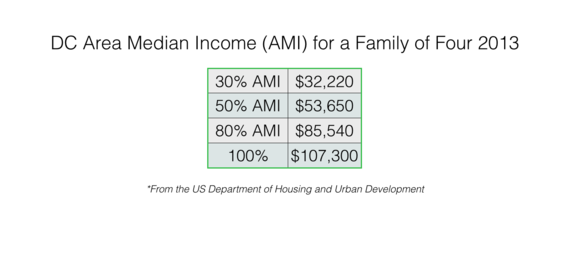

The fact is most of us use the term "affordable housing" as one that serves those in need. Though sometimes true, it is important to distinguish between "affordable" and "low income." We tend to use both as blanket terms to describe housing services provided to our most under resourced residents. However, The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the federal arm that oversees the development of subsidized housing in the United States, makes a quantitative distinction between "affordable" and "low income." HUD uses AMI (Area Median Income) to place residents on a spectrum of income relative to their city's median income. "Affordable housing" typically describes residences reserved for households on the higher end of this spectrum, while "low income housing" commonly refers to units available for residents on the lower end. In other words, the state of the art "affordable" residence around the corner most likely isn't serving a the demographic that typically comes to mind when discussing this topic.

When stakeholders consider "affordable housing" they are commonly referring to mixed-income residences underwritten to accommodate roughly 20 percent of their units for 30-80 percent AMI residents. For the Washington metropolitan area that includes households earning between $30,000 and $85,000 annually; incomes commonly associate with congressional staffers and consultants, not residents like Sasha.

"Low income housing" is typically used by the industry to describe housing reserved for residents that comprise 0-30 percent AMI. These few residences are often built and run by nonprofit organizations given the need of extensive wraparound services such as job training and healthcare. These residents are the most in need of stable and truly affordable housing.

By not being intentional about the language we use in housing, developers, equity investors and the city itself are able to depict themselves as benevolent community members whenever they broker a new deal and slap an affordable housing label on it. In reality, these new mixed-income affordable housing units do very little to serve mothers like Sasha or combat the ballooning 100,000-unit shortage for extremely low income households.

We need to start holding local housing stakeholders more accountable for the needs of not only our struggling middle class, but our most vulnerable residents as well. We have allowed developers and the city to put a new face to the poor. There are few market incentives for the private development of low income housing. When public-private affordable housing partnerships form in the shape of land grants, tax credits, and public funding, we must demand our cities make a far greater effort to preserve and construct more units that are truly "affordable" for our residents in greatest need.

If our city governments insist on privatizing the development of affordable housing, which the District has done for the past 30 years, then it is the responsibility of that same government to step in when market forces come up short. Housing is the mainstay of stability. It is the building block for our cities and empowers its residents to become wholesome members of the community. Impactful and intentional affordable housing is the first step to sustaining successful education and health outcomes and building a more prosperous city -- for all.