The Paradigm Shift

2016, by many indicators, will be the year classrooms go digital. Digital curricula have proliferated and become increasingly accredited, individual handheld devices are ubiquitous and have app ecosystems that hold much promise, and instructor tech savvy is at an all-time high.

But lost in the increasingly noisy edtech marketplace is a precise definition of what education is; what it's supposed to produce, the qualities it's supposed to engender. The reason a college education is considered so vital is because, at the end of it, a student has learned how to think.

That's not to say the American education system produces these results consistently. Not every American is a refined thinker. To use a topical example, it's no coincidence that a majority of the supporters of Donald Trump's presidential campaign didn't go to college.

Trump's followers aren't idiots, they're middle-class Americans who feel threatened in a changing world they were never given the tools to understand.

Real education, the kind for which students shell out hundreds of thousands of dollars to universities, isn't available online yet. Startups have understandably prioritized the foundation before the skylights. But the crazy thing is we're not that far off.

The Pregurgitation Trap: Why Tech And Education Haven't Clicked

I got my start as a educator working with a wonderful little program at Tufts University called STOMP (Student Teacher Outreach and Mentorship Program). One thing that stuck out throughout my time as a STOMPer was how much students helped each other learn.

The information came from the teacher, but the iteration in which the information truly resonated came from other students. Without the collaboration and trust of the shared experience, the learning was invariably far shallower.

As I moved on to teach SAT and other standardized tests for Kaplan Test Prep, the lesson was repeated. The best classes were those in which students knew or got to know each other, were willing to help one another, and were unafraid of translating my words into their own.

The plural of anecdote is not data, but these classes also seemed to see higher score increases on average. The students even tended to review me better and provide more positive feedback, sometimes in direct conflict to how I felt the class had gone.

The lesson was clear: real learning is social.

My first foray into edtech was humble, as I left Kaplan for a smaller education consultancy in New York and a varied role that included 1-on-1 Skype tutoring. The drawbacks were obvious: the student's mind was more prone to wander and more prone to defeatism.

With no one else in the room, no classmates and the instructor reduced to 2-D, there was none of the back-and-forth between instructor and student that marks real learning.

Without other students, and without me in the room, I was no longer educating. I was merely "pregurgitating" -- emitting information that the student could then regurgitate on the test. This is the real challenge facing online learning.

How do you replicate the lateral collaboration of the classroom? Not just the vertical information flow from teacher to student, but real exchange of ideas?

From Brick To Glass

Oddly enough, part of the answer to the question posed by educators will come from growth marketers. Without scalability and a positive feedback loop, without a means to get the tools in the hands of people who need them, the new-age classroom will never come to be.

It starts with an understanding of why the traditional classroom works, when it works well.

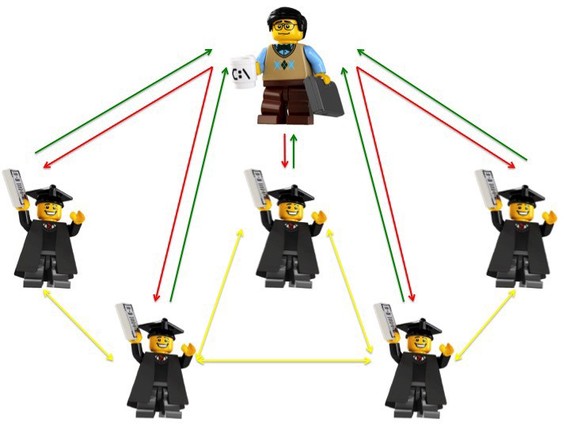

Picture the idea flow within a lively classroom discussion. The instructor gets the ball rolling, asks a provocative question, draws an equation on the board, and guides the discussion. The ideas are initially disseminated, as shown by red arrows, vertically.

But then students dig in and start interrogating. Ideas are modified, variables are moved, new connections are drawn in yellow. The new ideas even travel back up to the instructor in green. Suddenly the initial content has been reformatted, and the instructor shifts from creator to consumer. That's the experience e-learning has to drive towards.

Consider these the standards of excellence of world-class education.

1. Common interest: In other words, gravity. Students want to be around not just the instructor, but around their colleagues. Every participant needs to feel they have a role in the larger group that comprises the class.

2. Clearly defined facilitator: Instruction has to start somewhere. Someone has to supply the activation energy, the initial information, and continue to facilitate and moderate. We call it the Socratic method because someone has to play the role of Socrates.

3. Fluid content consumption and creation: This is where the wheat really separates from the chaff. When the shoe is on the other foot, the facilitator can (and should) be an avid content consumer. Social e-learning, in order to really scale, should be as content-driven as possible.

There are drawbacks to the traditional classroom model. One teacher can't handle more than 10 students well; beyond 20, the task quickly becomes Sisyphean. The good news is that the onus on the instructor to hold the classroom together can be mitigated with a social component.

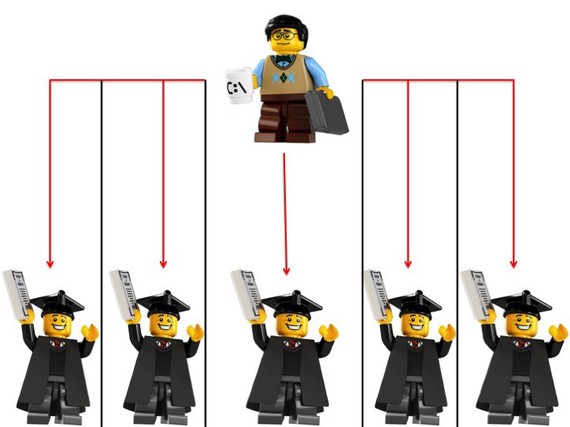

Individualized online learning has its place. But, as an example, I've mapped an MIT OpenCourseWare course the same way as I mapped the idea flow in a traditional classroom. The instructor disseminates information, and it flows down as many individual channels (computer screens, tablets) as there are students.

The scalability is obvious. Remove the lateral lanes for idea flow and you remove distraction. One instructor can create content that is then distributed thousands of times over. But the diagram looks vaguely like cattle chutes, and that's not a coincidence.

In individualized, on-demand learning modules, students can become content creators but have no means or desire to distribute to one another. The social element vanishes, and we're back to square one.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs plays in here as much as anywhere else. A great many people need to learn facts or skills first, before aspiring to social learning. But individualized, on-demand services don't replicate real quality education. At least, not yet.

Rubber to Road

It might not be the perfect time to adapt social networks and replicate collaborative education, although there are thankfully a great many startups attacking this with gusto. It will certainly be a monumental struggle. But when I contemplate the odds, I remember Malala Yousafzai.

We live in a world in which a girl needs to have Malala's boundless courage just to be educated. In the year 2016, we have the tools to change that. We can not only broaden horizons but deepen character. Hate and ignorance are learned; compassion and kindness can be too.

It's not enough to pat ourselves on the back when young women like her can derive an equation or speak English. It's not enough to pat ourselves on the back now that children in a few pockets of Africa can learn to code.

We have the means, today, to tear down the ivory towers.