National Adoption Awareness

By Presidential Decree, in 1984, adoption awareness was made an annual national event. And by another Presidential Decree, since 1995, November has been National Adoption Month. It is estimated that about two percent of Americans are adopted by unrelated families, 58 percent of Americans know an adoptee, and more than one-third of Americans have considered adoption.

Transracial and Transnational Adoption

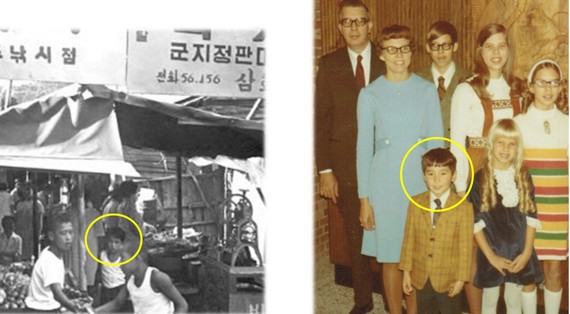

Because of the conflicted and polarizing views and history of transracial and transnational adoption, this topic is less often addressed, during National Adoption Month or any other time. Since I am a transracial and transnational adoptee, have written a book on the topic, and part of my doctoral research involves transracial and transnational adoptees and the insights and implications such adoptive populations may offer for education success and life outcomes, I decided to discuss this topic here.

I know that there are a range of views on this subject, many with great intentions, valid critical concerns and issues, and solid rationales. I know that some people argue that eliminating transnational or transracial adoption puts more pressure on nations or communities to give more support for single mothers or for in-country, in-community adoption. Or that it stops child trafficking. But I have some deep reservations about eliminating options, especially if it may disproportionately impact a society's most vulnerable.

I strongly agree that we should absolutely do as much as possible to let parents be able to choose to keep their children and eliminate all incentives not to and that we need to protect children. But we also know that relinquishment, abandonment, and being orphaned will happen.

Eliminating a known, proven, highly successful social intervention -- far superior to institutionalization or foster care -- would seem far less than wise and may be significantly short of moral.

By analogy, having medical interventions that cure diseases may theoretically lessen some pressure on individuals to live healthier life styles or avoid known risks. But no one would argue that we should eliminate a known, effective cure for a terrible malady.

Adoption as Intervention

And we know that many of the most successful medical interventions for some of the most horrific maladies -- like childhood cancer -- are often also keenly painful with severe side effects; can leave lasting, life-long scars; and are not guaranteed a perfect outcome. Yet no one seriously suggests that such interventions be eliminated because of not being guaranteed, free of pain or of side effects.

Adoptees have all suffered a tragic, negative life circumstance. But adoption is not the malady. The underlying malady is relinquishment. Every adoptee first suffered relinquishment, abandonment, or being orphaned by their biological mother and father, such that they needed care by others.

Adoption for the Right Reasons

Acknowledging this fact is not the same as suggesting that adoption is always the go-to option or that people should adopt simply to play rescuer of or hero to children in tragic circumstances. The decision to become a parent, whether biological or adoptive, should be a well-considered and deeply self-searched one; one that includes the best interests and needs of parents, family, and community, but -- most importantly -- the child and his or her future.

Although it is highly successful, adoption -- for many, maybe even for the vast majority -- can be an extremely painful intervention. I know, personally, that it can be soul-searing and often does cause its own problems and side effects that linger throughout life.

In a perfect world, no child would ever be relinquished or abandoned or orphaned. But parents are limited human beings -- as are we all. And some suffer their own singular life crises, die unexpectedly or tragically or far too early. Because of this, there always have been and will always be children of all races, all communities, and all nations who suffer the tragedy of relinquishment, abandonment, or being orphaned -- intentionally or otherwise.

The Most Basic Right

Reality has also shown that social norms, stigmas, and practice are not changed overnight by laws, statutes, and prohibitions. Because of this, for some children the best chance they have for the love, care, and future that all children deserve may be transracial or transnational adoption.

In such cases, to do nothing would seem criminal. But to eliminate the most potentially successful option for that child, even as a choice to be considered, seems something very short of the most basic humanity that should be given toward the most blameless and helpless members -- the relinquished, abandoned, or orphaned children -- of any race, any nation, any society.

Like and share this article via Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn.

Joel L. A. Peterson is the award-winning author of the novel, "Dreams of My Mothers" (Huff Publishing Associates, March, 2015).

"Compelling, candid, exceptionally well written, "Dreams of My Mothers" is a powerful read that will linger in the mind and memory long after it is finished. Very highly recommended."

-- Midwest Book Review

For more articles by the author, become a fan by clicking the "fan" button at the top of the page.

Learn more about the author and his book at:

www.dreamsofmymothers.com

On Facebook