Last month, a study in the Cognitive Science journal found that kids exposed to religion struggle with distinguishing between fantasy and reality. Are lesson plans geared toward kids to blame?

The research, published by Kathleen H. Corriveau, Eva E. Chen and Paul L. Harris, found the following, according to their research abstract:

In two studies, 5- and 6-year-old children were questioned about the status of the protagonist embedded in three different types of stories. In realistic stories that only included ordinary events, all children, irrespective of family background and schooling, claimed that the protagonist was a real person. In religious stories that included ordinarily impossible events brought about by divine intervention, claims about the status of the protagonist varied sharply with exposure to religion.

Children who went to church or were enrolled in a parochial school, or both, judged the protagonist in religious stories to be a real person, whereas secular children with no such exposure to religion judged the protagonist in religious stories to be fictional. Children's upbringing was also related to their judgment about the protagonist in fantastical stories that included ordinarily impossible events whether brought about by magic (Study 1) or without reference to magic (Study 2). Secular children were more likely than religious children to judge the protagonist in such fantastical stories to be fictional. The results suggest that exposure to religious ideas has a powerful impact on children's differentiation between reality and fiction, not just for religious stories but also for fantastical stories.

In the Huffington Post, the researchers wrote:

Some media reports about our research have said, on the basis of these results, that religious children cannot tell fact from fiction. We doubt such a conclusion is warranted. Our interpretation is different. Religious children are encouraged to think that miracles are possible -- and so for them, a story that includes a miracle is not obviously fictional. Non-religious children, by contrast, receive less encouragement to think that miracles are possible -- and so for them a story that includes a miracle is likely to be made up.

Mark Joseph Stern from Slate Magazine wrote "Religions tend to be founded on miracles stories -- exactly the thing religious kids had trouble distinguishing from reality."

The assumption is that religion is dominated by a focus on the fantastic, such as "miracle stories," as opposed to teachings on morality, or how to live the our world today, such as those featured in "The Sermon on the Mount."

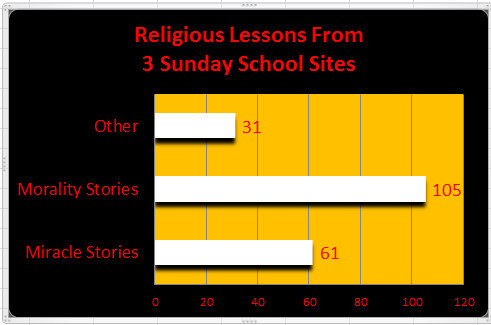

To determine whether children are given more lessons on miracles or morality, I examined three sets of lesson plans used by Sunday School teachers. These include DLTK-Bible.com, SundaySchoolResources.com and CreativeBibleStudy.com.

For DLTK-Bible.com, I looked at how many stories involved the miracle stories, where divine events reign, as opposed to stories that involve humans making good or bad choices, without the fantastic emerging. For the Old Testament stories, DLTK-Bible.com had 10 that would be considered miracle stories, while 12 did not involve miracles as a key or even secondary element in the story. Among their New Testament stories, DLTK-Bible.com had seven that would involve miracles, while the other 14 dealt with parables, lessons or events where a miracle does not occur.

The site "SundaySchoolResources.com" similarly breaks lessons into Old and New Testament categories. Among the seven listed in the Old Testament, there were four with a miracle-bent, while the other three dealt more with morality and elements not requiring a miracle. For the 19 New Testament cases, six involved miracles or clear divine intervention. The other 13 dealt with morality tales clearly using a metaphor, or cases where Jesus summons followers, preaches about good and bad behavior or tells tales clearly identifying hypothetical cases or metaphors to teach a lesson.

Finally, the CreativeBibleStudy.com listed a number of sermons on the sermons4kids.com section. Of these, 34 had fantastic elements, 63 had what the researchers would call it "without reference to magic," and 31 weren't really bible stories (the "I love Jesus" balloon or lesson on the importance of Veteran's Day).

Corriveau, Chen and Harris point out that there are some benefits to looking at stories with fantastic elements. "In some instances, the ability to suspend disbelief might be an asset to learning. For example, when learning counterintuitive phenomena -- such as the entirety of modern physics -- the ability to imagine improbable events might aid in acquiring knowledge."

The research I have conducted reveals that miracle tales do not dominate today's bible lessons. In fact, they don't always make up a majority of the stories taught to kids. They are present, but as the researchers from Cognitive Science found, that's not always a bad thing. But if all you did was teach the ordinarily impossible events, a kid might have a harder time not being tricked by other non-religious fantasy stories.

John A. Tures is a professor of political science at LaGrange College in LaGrange, Ga. He can be reached at jtures@lagrange.edu.