On the morning of September 28, 1901, in the town of Balangiga on the island of Samar in the Philippines, a procession of worshippers accompanied the coffins of children who apparently died of cholera into the local church for dawn service. At 6:45 a.m., Valeriano Abanador, the local Chief of Police, grabbed the rifle from private Adolph Gamlin of Company C, 9th U.S. Infantry Regiment and knocked him unconscious with a blow to the head. A church bell rang out and the worshippers retrieved bolos, machete-like knives used for clearing vegetation, from the coffins. 500 Balangiga townspeople then entered a mess hall where members of Company C were eating breakfast and killed some 48 out of 78 soldiers while severely injuring 22, the worst defeat experienced by the U.S. Army since the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876.

In retaliation, General Jacob H. Smith vowed to turn the province into a "howling wilderness," telling his troops, "I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn; the more you kill and burn, the more you will please me." Jacob "Howling Jake" Smith infamously ordered his soldiers to "kill everyone over the age of ten" while conducting a scorched-earth policy that involved burning villages and crops. Smith was court-martialed for violating military discipline, but never formally punished, and forced into retirement.

New York Journal editorial cartoon, May 5, 1902, criticizing Smith's orders. The bottom caption reads, "Criminals Because They Were Born Ten Years Before We Took The Philippines."

New York Journal editorial cartoon, May 5, 1902, criticizing Smith's orders. The bottom caption reads, "Criminals Because They Were Born Ten Years Before We Took The Philippines."

The "Balangiga Massacre," a name used by both sides to contrary ends, concluded when Americans appropriated three bells from the church as spoils of war and brought them back home. Two bells are currently displayed at "Trophy Park" inside F.E. Warren Air Base near Cheyenne, Wyo. The third bell, supposedly the one that signaled the attack, went with the 9th Infantry Division, and is now located in a military museum at Camp Red Cloud in South Korea.

What were the historical conditions that led to the Balangiga Massacre?

Tensions between the Balangiga townspeople and the U.S. military escalated in the context of the Philippine-American War, a war many Americans have probably never heard of, one of America's many "forgotten wars."

In 1898, the battleship Maine was sent to Havana to support Cuba's struggle for independence from Spain. The ship was blown up on February 15, 1898. Newspapers immediately blamed the Spanish, thus conveniently serving as a pretext for war. A squadron of warships led by Commodore George Dewey was sent to Manila and quickly defeated the Spanish in the Battle of Manila Bay. The exact cause of the "sinking of the Maine" is still subject to speculation. Many believe the explosion was caused by a coal bunker fire.

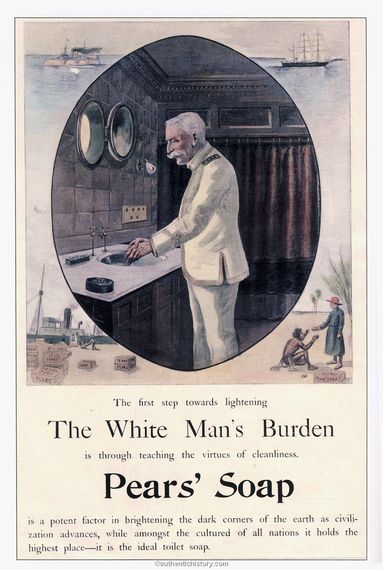

An advertisement for Pears' Soap featuring Commodore Dewey, "The first step toward lightening The White Man's Burden is through teaching the virtues of cleanliness."

An advertisement for Pears' Soap featuring Commodore Dewey, "The first step toward lightening The White Man's Burden is through teaching the virtues of cleanliness."

Emilio Aguinaldo led Philippine forces against the Spanish during the Philippine Revolution (1896-1897), and was led to believe that the U.S. was coming to fight for Philippine independence. On July 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared an independent Philippine republic. Yet the U.S. refused to recognize this republic, and proceeded to take over where Spain left off, thus leading to a brutal counter-revolutionary war waged by the U.S. against a people who had suffered under and struggled against a violently corrupt Spanish empire for three hundred years. The war officially ended in 1902, but fighting continued until 1912.

One of the most vocal opponents of the war in the U.S. was Mark Twain. Twain was a founding member and vice president of the Anti-Imperialist League of New York, a group that also included industrialist Andrew Carnegie and labor leader Samuel Gompers. In "To the Person Sitting in Darkness," an essay published in the North American Review in 1901, Twain exposes the rhetoric of moral and racial uplift -- "white man's burden," civilizing mission" -- to the reality of imperialist violence being perpetrated by Western nations in places like South Africa, China, Cuba, and the Philippines. Turning to the Philippine-American War at the end of the essay, Twain's sarcasm cuts deep into the belly of the emerging American empire in the Pacific, "There must be two Americas: one that sets the captive free, and one that takes a once-captive's new freedom away from him, and picks a quarrel with him with nothing to found it on; then kills him to get his land."

In an even darker essay, "Comments on the Moro Massacre" (1906), Twain surveys the newspaper headlines describing the slaughter of Muslim Moro rebels and villagers who had retreated into the crater of a dormant volcano on the island of Jolo, many of whom were women and children. After seeing the heading "Death List Now 900," Twain sardonically declared, "I was never so enthusiastically proud of the flag till now!" Also known as the Bud Dajo Massacre, this ugly moment in the history of U.S. imperialism is hauntingly reenacted in the experimental documentary by Sari Dalena and Camilla Griggers, Memories of a Forgotten War (2002).

The Philippines gained independence in 1946 and got most of its land back, with the exception of over 20 U.S. military bases, but is still waiting for the bells of Balangiga to be returned.

Since independence, Catholic leaders in both the U.S. and the Philippines have worked to have the bells returned to Balangiga. This movement almost achieved its goal in 1994 when President Bill Clinton met with President Fidel Ramos. After the meeting, Clinton announced that he was prepared to return the bells, but impeachment proceedings diverted his attention.

In 2005, Wyoming veterans voted to return the bells, but were blocked by the governor, who claimed that they represented "a significant part of Wyoming's military heritage," even though, as Robin Hemley pointed out in a Wall Street Journal article on the issue, no one from Wyoming served at Balangiga.

One influential voice in the movement to return the bells has been E. Jean Wall, the daughter of Adolph Gamlin. Gamlim survived the massacre but was haunted by it for the rest of his life. Wall initially opposed returning the bells, but after a visit to Balangiga, changed her mind. In addition to arguing for the bells' return, Wall has been active, along with the residents of Balangiga, in promoting healing and reconciliation between the descendants of Balangiga and Company C.

The bells of Balangiga represent different things to different groups. For many Filipinos, they are a symbol of the long, hard struggle for independence, much like the Liberty Bell in U.S. history. For the U.S. military, they are the spoils of war, compensation for the loss of life on that terrible day. For Catholics, they are a religious symbol that needs to be returned to its proper home in the church. For peace activists, the bells are a symbol of reconciliation, a much-needed symbol given the intensifying militarization of the Pacific as seen in the return of the U.S. military to the Philippines. And for the people of Balangiga, the bells are a symbol which brings together history, religion, and community, and they understandably want them returned.

The people of Balangiga were poor, and yet the church raised enough money to have the bells cast. Townspeople initially welcomed Company C to Balangiga and the two groups enjoyed friendly relations for a brief period, playing baseball and drinking tuba (coconut wine) together. Tensions escalated when the invading army began to oppress the local population by garrisoning them, cutting off food supplies, and assaulting young women. In order to preserve their dignity and independence, the townspeople fought back, bolos and imagination against rifles and gatling guns, an action that should garner the respect of Americans who fought a similar war of independence against a colonial power.

In 2013, Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) devastated the town of Balangiga. One of the few buildings left standing was a belfry built in 1998 in anticipation of the return of the bells. Perhaps a reenergized movement linking the Philippines, the U.S., and South Korea can help fill the empty belfry so that the people of Balangiga can hear their bells ring once again.