With just three weeks and three holidays between now and the Iowa Caucuses, the nation is soon to be inundated with public opinion surveys probing virtually every corner of the Iowa political psyche.

To casual observers, this is a run-of-the-mill modern day treatment of a major political event. But insiders understand the Iowa caucuses are not your run-of-the-mill political process, but instead are a throw-back to days when neighbor met neighbor and traded wisdom in the town square.

The Iowa caucuses require voters to go to a local school, church basement, private home or similar meeting place to spend between 90 minutes and two hours to register their preference. The process is a mixture of discussion, debating, a little horse-trading, and some consensus-building between neighbors. Anything can happen.

Some say the dynamic at play in the caucuses cannot be captured by a survey, and while the final outcome is impossible to predict exactly, preferences and trends leading up to the event can give us a pretty good picture.

In other words, the Iowa caucuses can be accurately polled.

Our survey work leading up to the 2004 caucuses is a good example. In Zogby surveys conducted in the months leading up to the caucuses, Zogby International asked about the "horserace" question of who likely caucus-goers would support. We also asked whether Iowa Democrats believed President Bush could be defeated, and whether they preferred a Democratic challenger who stood up for what they believed, or instead preferred a candidate who could win the election.

For months, Iowa Democrats said they did not think Bush could be defeated, and that they wanted a Democratic challenger who would at least stand up for what he believed and would hold the president's feet to the political fire, especially over the war in Iraq.

Given their feelings on these two questions, it was not a surprise that their favored candidate was former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean, an anti-war firebrand with a flair for using the Internet to organize millions of campaign supporters nationwide.

However, just after the new year of 2004 began, Zogby polling found a startling change in the mindset of Iowa Democrats. In the aftermath of the capture of Saddam Hussein in mid-December, 2003, they apparently began to rethink the 2004 elections, perhaps thinking the election could turn on more than just the war in Iraq. Whatever the reason, Democrats began to think Bush could be defeated. With that change of heart came a change of momentum.

Our polling showed that Dean was peaking, and that others, including Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry -- the eventual winner -- began gaining steam.

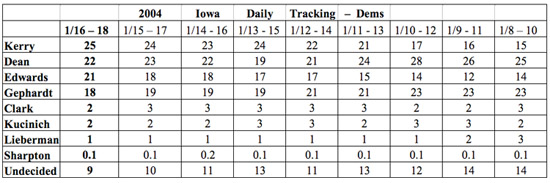

At the start of Zogby's daily tracking in Iowa, on Jan. 10, 2004, Kerry stood 10 full points behind Dean, 25% to 15%. Missouri Congressman Richard Gephardt was then in a close second at 23%, while North Carolina Sen. John Edwards was back at 14%. The tracking survey included a rolling survey covering the three latest days of polling - when a new day's results were added, the fourth-day results were pushed out the back end of the rolling average.

The second day the rolling average was published eight days before the caucuses, Dean had bounced up slightly to 26%, while Gephardt, locked in a furious media battle with Dean, held steady. Kerry ticked up one point to 16%, and Edwards dropped two points to 12%. The next day, Dean hit his high-water mark of 28%, while Gephardt yet again remained steady at 23%. Kerry gained another single point, while Edwards recovered the two points he had lost the day before.

From that point through the next week until the caucuses were held, Kerry and Edwards traded on their experience and electability, gaining steadily until the caucuses, while Gephardt and Dean continued slow fades into the ranks of the also-rans.

In the run-up to the caucuses, Dean and Gephardt, the one-time front-runners, brutally attacked each other with campaign advertisements, leaving Kerry and Edwards to benefit by avoiding the firefight and slipping past them in the end. Exit polls showed that Iowans were not as motivated by the two issues that Dean and Gephardt had championed most -- opposition to the war and to unfair international trade deals. Instead, health care and broader economic concerns motivated voters, the polling showed, and a huge volume of voters who made up their minds late in the process rejected the negative attacks of Dean and Gephardt in favor of the more optimistic messages carried by Kerry and Edwards.

When the final results of the caucuses were known, the four candidates finished in exactly the order indicated by the Zogby polls before the caucuses, though the percentages were different because undecided voters had finally made up their minds. Can we predict the exact results of the Iowa caucuses ahead of time? The answer is simple: no. But that is not the purpose of political polling. As I mentioned earlier, there is no way to predict the neighbor-to-neighbor dynamic inside a caucus setting, and especially the effect that setting will have on those caucus-goers who show up to the events yet undecided.

But broad contours of the political landscape in Iowa can be determined by pre-caucus polling -- the rest is up to the voters.