In 1950, Albert Einstein wrote to console Robert S. Marcus - then Political Director of the World Jewish Congress - who had recently lost a son to polio:

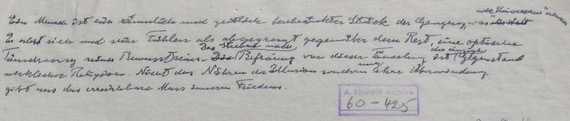

Dear Mr. Marcus,

A human being is a part of the whole, called by us "Universe", a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest -- a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. The striving to free oneself from this delusion is the one issue of true religion. Not to nourish the delusion but to try to overcome it is the way to reach the attainable measure of peace of mind.

With my best wishes,

sincerely yours,

Albert Einstein

Can that really be said of Judaism - that its 'one issue' is a 'striving to free oneself' from an 'optical delusion of one's consciousness,' which is the experience of being 'something separated from the rest?'

Are we not "a people who dwell apart, not reckoned among the nations"? (Numbers 23:9) Isn't our story of exodus and redemption rooted in our being "distinguished" or "exceptional" in Egypt, according to the Haggadah? Isn't there specific alarm throughout the Jewish world this week as wildfires, stoked by arson, ravage Israel - and isn't the same true, metaphorically, just about always?

Or take the example of the Torah's stories this week. When Abraham insists on purchasing a burial cave from the Hittites in Hebron, following the death of his wife, Sarah, rather than accepting the parcel of land as a gift, is that not resistance to entanglement with others? Is the same not true of Abraham's adjuring his servant, "I demand you swear by the Eternal One, the God of heaven and the God of the earth, that you will not take a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites among whom I dwell, but will go to the land of my birth and get a wife for my son Isaac." (Genesis 24:3)

Could there be a tradition more obsessed with being 'separated from the rest?'

But consider what it is that identifies Rebekah, in the Torah this week, as the partner destined for Abraham's son, Isaac:

"The servant hurried to meet her and said, 'Please give me a little water from your jar.' She said, 'Drink, my lord,' and quickly lowered the jar to her hands and gave him a drink. After she had given him to drink, she said, 'I shall draw water for your camels too, until they have had enough to drink.' So she quickly emptied her jar into the trough, ran back to the well to draw more water, and drew enough for all his camels." (Genesis 24:17-19)

The story taking place far from Abraham's own camp - also distinguished, per last week's reading, by its kindness to wayfarers - it seems we are meant to understand that Rebekah is naturally possessed of a giving spirit that matches the ethos and the tradition of Abraham.

In his chapters on gifts to those in need, Maimonides (1135-1204) not only sets forth famous gradations, ranging from staking a compatriot in need to a share in a joint business venture - "the greatest level, above which there is no greater" - all the way down to simple handouts given when implored. Maimonides also delineates what we might call circles of priority, from one's own parents and family, if they are in need, on outward.

One may criticize medieval Maimonides for falling notably short of biblical Rebekah and her generosity to a stranger, inasmuch as what Maimonides actually deems "the greatest level, above which there is no greater" is "to support a fellow Jew by endowing him with a gift or loan, or entering into a partnership with him, or finding employment for him, in order to strengthen his hand until he need no longer be dependent upon others."

Ze'ev Maghen vehemently and at length, in his John Lennon and the Jews: A Philosophical Rampage, insists that actual love, true love, is inherently particular, and, by its nature, is felt only for someone close whom, a priori, one can call one's own. (One thinks of "my sister my bride" throughout the Song of Songs, e.g. 4:9, 4:12) Generalized love of an "imagine there's no countries"-sort, Maghen argues, tends dangerously and frequently to accompany and reflect shortcoming on the interpersonal level; think Mohandas K. Gandhi - or Albert Einstein, for that matter. If, within our families and tribes and peoples and nations, we practice real love, then, Maghen argues, and only then, the world will be full of true love, and we'll all make out alright. So Maghen rushes to the defense of Maimonides - somewhat stumbling over Rebekah, not to mention divine admonishments to love the stranger, I would say.

But if love of the affinate-infatuation-sort isn't all you need, what more is there?

Ever since reading it, I am haunted by the account in the Zohar (the 13th century seminal text of Jewish mysticism) of the last conscious thought of the individual soul in its journey through death. According to the Zohar, on the verge of the obliterating subsumption back into the One - the creature helpless to hang onto itself and its particular objectives, in the face of the Creator - in the last moment of the "delusion," as Einstein would put it, of separateness and duality - comes the realization: all of this has been an act of service.

How good, how worthy - or how not - will be the service one has rendered, when it comes, as we all must come, to that moment? What will one have done for this world of the Eternal One?

The emotional capacity for love may be essential in the inculcation and the pursuit of goodness - but tzedakah, actual righteousness, must transcend passion and infatuation, and must amount to more - must strive toward more than ensconcing our families and tribes in jewel boxes of abundance. If we love truly, and seek the right, then the more we are privileged with capacity and ability, the more we will serve, and the more the world, as a oneness, will benefit from our having been here.