I un-learned the word "girl" in my first week as an undergraduate at Brown. Female fellow students were women, and young men learned that swiftly. So it remains a considerable surprise - in my return to college, so to speak - to discover the words "girl" and "girls" in such currency among young women at Harvard, used by preference of themselves and of their peers.

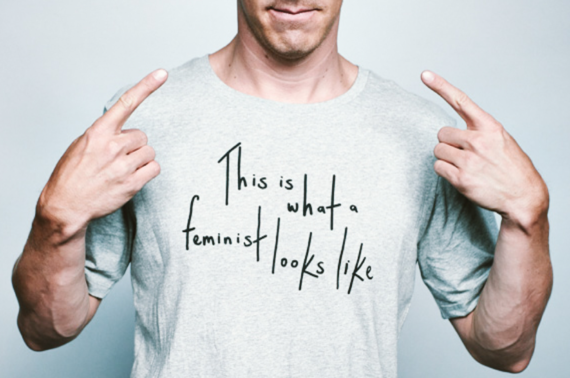

As a feminist, I know better than to tell women what to call themselves. I should know better, also, than to "mansplain feminism" (as a young, male, feminist friend put it recently in an ironic preface to an observation of his own in a summer course I taught on the biblical Song of Songs).

Still, I think about the terminology of "girls," and what norms and expectations go with it, whenever I walk out of my office late on a Friday or Saturday evening and see undergrads, dressed as for cocktail parties (no, more specifically, cocktail parties in Moscow, not implying winter garments), tottering to and from their destinations along Mount Auburn Street or through the alleyway between Rosovsky Hall and Lowell House. And I think about this, too, when I hear, often, about ways in which Harvard can be a less than safe and happy place for young women in the College.

Think, if you were walking down a midtown city street, what you might expect to find in connection with a sign announcing "Girls!" as opposed to one proclaiming "Women!" Cambridge, on a weekend evening, can often seem to be largely about the former, where one might well have expected a greater quotient of the latter.

I think about all this, too, in a week when the Orthodox Union (OU) has joined the Rabbinic Council of America, the Young Israel movement, and Aguda - organizations representing present-day Jewish orthodoxy - in banning women (again) from serving in clergy- or quasi-rabbinic roles in orthodox congregations. The pronouncement, with its urgings and encouragements for female members of orthodox communities to stay engaged in Torah-learning notwithstanding, reads as though properly addressed to girls - which is to say, as if its exclusively male authors have little concern about being responded to by women.

This comes in a week when our reading in the Torah features Miriam the prophetess leading the Israelite women in song and dance at the Red Sea. And the accompanying reading, from the book of Judges, tells the story of how, in her own later time, Deborah the prophetess, who "judged Israel in those days" (Judges, chapter 4) summoned the people's leading warrior, Barak ben Abinoam, to send him in battle against the Canaanite forces of Jabin, king of Hazor and the warrior chieftain, Sisera.

Barak says to Deborah, "If you go with me, then I will go; but if you will not go with me, I will not go," and Deborah replies, "I will go with you, howbeit your own fame will not be upon this path on which you go, for the Eternal One will give Sisera into the hand of a woman." If that is meant to shame Barak for behaving in a less than masculine way in his hope that Deborah will accompany him, then it may be a dubious example - but, on the other hand, if it is a contention about honesty with regard to how we actually need and learn from one another, then I'll take it, as an exchange with relevance for our times.

The OU's ruling recalls to mind something Letty Cottin Pogrebin, a founding editor of Ms. magazine, once wrote about the treatment of women in historical rabbinic law, in halakha. She observed, "A life of Torah is embodied in Hillel's injunction, 'Do not do unto others what you would not have them do unto you.' Men would not like done unto them what is done unto women in the name of halakha. For me, that is that."

Or, as Tikva Frymer-Kensky, of blessed memory, wrote decades ago, in a pioneering essay entitled "The Feminist Challenge to Halakha" - "the basic principle of feminism, the bottom line, is that women are human beings, that they must be considered full human beings, and that to do anything else is unacceptable. Anything else is patriarchy. It may be patriarchy with an oppressive face, or patriarchy with a paternalistic face, or patriarchy at its most benevolent, but it is always patriarchy to say that women are other than fully human. This basic principle seems to us so self-evident as to not need being said. But it does need to be said, over and over, for our newspapers and our history books tell us of the many ways in which that principle is violated abroad and at home every day."

Around the same time, Judith Plaskow retold the story of Eden, imagining a return to the Garden on the part of Lilith - the Holy Blessed One's first attempt at creating woman, coequal with Adam, driven away by the first man who could not tolerate such a creature. As Plaskow tells it:

"Lilith, all alone, attempted from time to time to rejoin the human community in the garden. After her first fruitless attempt to breach its walls, Adam worked hard to build them stronger, even getting Eve to help him. He told her fearsome stories of the demon Lilith who threatens women in childbirth and steals children from their cradles in the middle of the night. The second time Lilith came, she stormed the garden's main gate, and a great battle ensued between her and Adam in which she was finally defeated. This time, however, before Lilith got away, Eve got a glimpse of her and saw she was a woman like herself."

And sometime later, in consequence of that glimpse, as Plaskow imagines: "Adam was puzzled by Eve's comings and goings, and disturbed by what he sensed to be her new attitude toward him. He talked to God about it, and God, having his own problems with Adam and a somewhat broader perspective, was able to help out a little--but he was confused, too. Something had failed to go according to plan. As in the days of Abraham, he needed counsel from his children. 'I am who I am,' thought God, 'but I must become who I will become.'"

Frymer-Kensky, by way of remedy in her recent day, suggested bringing about a situation in which the principle and precedent of a rabbinic ruling for extraordinary or perilous times (a hora'at sha'ah - a "ruling of the exigent moment") might properly be invoked. "If women want to redress the basic inequity of the halakha, the skewing of the law so that men are the agents and women the objects of actions," she wrote, "then we have to create a situation where the whole system is endangered without [such a redress], and it becomes a hora'at sha'ah to declare women full proactive human beings. And that maybe only women can do."

Sometimes it seems one might aptly say something similar about some of social life in Harvard College. Sometimes it seems most sensible simply to support students in creating alternatives - but sometimes it is difficult not to imagine, if not a Lilith-like storming of certain final club and other gates, at least an awakening, of all genders, that might leave the spaces inside empty of "girls."