"Now," says God to Moses, "draw near to you Aaron your brother, and his sons with him, from among the Children of Israel, that he may be a priest to me - Aaron, Nadav and Avihu, Elazar and Itamar, the sons of Aaron." (Exodus 28:1)

In our democratic times, the notion of a caste elected by birth to intermediate between the nation and God seems not just archaic but spiritually baffling. We tend to focus on religious experience in the first person. We engage voluntarily, because we are moved to do so. And if we are so moved, why should anybody else be privileged with greater duty and proximity?

Jewish tradition, since the earliest rabbis, makes divine service an individual responsibility, incumbent on everyone. What, on the other hand, was spiritually compelling to our ancient ancestors - especially to those distant from the ritual center - in knowing that somewhere, someone was keeping altar-fires burning? Where was the spiritual uplift in that for the farmer far afield?

First, let us appreciate just how aggrandized the High Priest was for our forebears.

"How he was honored in the midst of the people in his emerging from the sanctuary! - as the morning star in the midst of a cloud; as the moon at the full; as the sun shining upon the temple of the Most High; as the rainbow giving light in the bright clouds; as the flower of roses in the spring of the year; as lilies by the rivers of waters; as the branches of the frankincense tree in the time of summer; as fire and incense in the censer; as a vessel of beaten gold set with all manner of precious stones; as a fair olive tree budding forth fruit; and as a cypress tree that grows up to the clouds - when he put on the robe of honor, and was clothed with the perfection of glory, when he went up to the holy altar, and made the garment of holiness honorable."

So says the book of Ecclesiasticus - a.k.a. Ben Sira, or Sirach - composed when the Temple still stood in Jerusalem. (Sirach 50:5-11)

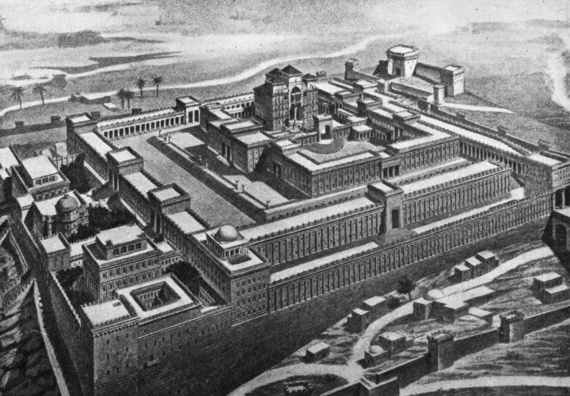

A pilgrim's account relayed in the Letter of Aristeas to Philocrates, describes the Temple and the priestly service, as viewed from one of the parapets of Jerusalem's citadel, saying, "A person would think he had come out of this world and into another one - I emphatically assert that every man who comes near the spectacle of what I have described will experience astonishment and amazement beyond words, his very being transformed by the hallowed arrangement of every single detail."

Our ancient rabbis imagined the experience at the epicenter of that vision to be transformative as well. Playing on the biblical verse prescribing "No man shall be in the Tent of Meeting from the time Aaron goes in to make atonement in the Most Holy Place until he comes out" (Leviticus 16:17), our sages suggested, "The High Priest himself was not a 'man' at that moment; but when the spirit of holiness rested upon him, his face flamed like torches." Which was a way of saying that this was as close as a living human being got to being an angel - pretty close.

Our ancestors seem to have cherished the thought that one human being, on behalf of the entire people, was duty-bound to inhabit that experience.

He must have been a remarkable man, the person privileged to stand in that place and inhabit that role - not so? Should we not imagine the High Priest deeply learned, rigorously trained from birth for his sacred tasks?

Perhaps not. Consider the following narrations, excerpted from the first code of rabbinic law, the Mishnah of 200 C.E:

"Elders of the court would read before him from the readings of the day. They would say, 'My lord High Priest, read yourself, perhaps you have forgotten, or perhaps you have never learned.' On the eve of the Day of Atonement, they would place him in the eastern gate, and make bulls, and rams, and lambs pass before him, so that he would recognize them in the service. If he was wise, he would expound upon the readings. If not, the elders would expound before him. If he was accustomed to reading, he would read. If not, they would read before him from the books of Job, Ezra, and Chronicles."

Rather than a guaranteed scholar or certified seer, the High Priest, by this account, was an exalted Everyman. He might be a highborn illiterate, with hardly the pastoral experience to tell a bullock from a sheep, and yet be stationed at the very fulcrum between God and the people.

What to make of this accidental priest, spiritually? Or rather, what more to make of him than the suspicions and the squabbles that did indeed arise in a time when priesthoods were not only ritual phenomena but also the aristocratic arms of revenue collection, the ancient IRS - which certainly was the case in the Persian empire, under which the second Jerusalem Temple was built, and in the Roman empire, in which Judea became a province?

In true Jewish fashion, let me answer with another set of questions:

For all our meritocracies and our specializations, how prepared are any of us for where we find ourselves? Do we stand in our stations wholly on account of our merits and accomplishments? Amid our most lofty experiences, are we sure that there are no others equally or better suited if only given the same opportunities? And, in the face of the Infinite, how grand is the greatest of us?

I ask all this not to induce self-deprecation or self-doubt - and not entirely to exculpate our ancestors' ideas of inheritance either - but to remind us of the inexpugnable presence in our lives of good fortune and of grace. We stand atop the high places of the world - if not we, who else? Our view from here is darn near infinite, and aweing. In other words, the High Priest, by fair terms, may be a simpleton, which is important to remember - and yet...!