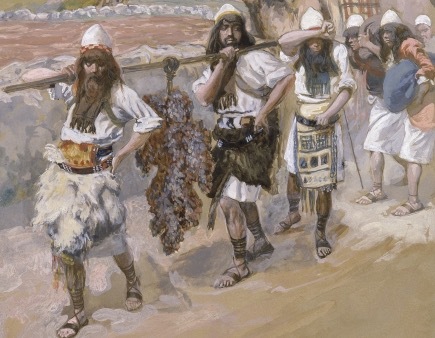

In our reading from the Torah this week, ten of the twelve scouts whom Moses sends to scope out the Promised Land give a daunting and discouraging report upon their return.

Among the things they say: "The land we have passed through is a land that devours its own inhabitants, and all the populace that we saw in it were people of great stature." (Numbers 13:32)

In the passage's plain sense, in its context, the spies were saying that Canaan was a fierce and inhospitable land full of giants, an unlikely new home for Israel.

Taking the passage out of context, I once observed of a certain educational institution - I won't specify which, except to say that, thank heavens, it is not one with which I am currently or even recently associated - that it was 'a land that devoured its own inhabitants, though those who constituted it were people of great stature.'

Unfortunately there are enough such places that those words, so applied, may ring a bell. I was speaking of a place that tended to fill its denizens with miserable self doubt and mistrust of one another, though it was populated, when one looked at its individuals, by dedicated young people seeking to do good, and by accomplished elders who ought to have been able to encourage them. Despite those ingredients, a culture had developed, over decades and even generations, in which teachers behaved like the adult children of abusive academic parents, in turn imparting insecure and sanctimonious judgementalism and cynicism to students.

But what I am really getting at and heading toward - with that shudder-inducing walk down a dark alley of memory lane - is the importance of the example set by the other two of the twelve scouts in our Torah-reading. These are the ones who say, 'Have faith, we can do it.'

Writing in the Warsaw Ghetto, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira of Piaseczno (1889-1943), whom I have mentioned before in these blog-posts, mused on the question of why the two encouraging scouts, Joshua and Caleb, did not mount a rational and logic-based argument against the other ten who, after all, were pointing at reasonably legitimate concerns.

In the most discouraging of settings, Rabbi Shapira used the story of the scouts to teach the importance of cultivating faith and trust not only where one might see a clear and natural path to one's own salvation, but especially "where, heaven forbid, one may see no opening to one's own deliverance by any rational or natural measure."

And if you say, 'Well that's nice, but Rabbi Shapira died anyhow in the Holocaust, didn't he - so what of his faith?' I will respond by observing how, three quarters of a century later, his teachings inspire, uplift, encourage, and live on.

In essence Rabbi Shapira indicates the crucial importance of the tone one sets - and, by all accounts and by the evidence of his own teachings, he himself steadfastly set an example of never giving up on the divine light within oneself and in every member of one's people.

Malachy McCourt, well acquainted with discouraging circumstances of a different variety, once observed in a New York Times interview, "Resentment is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die." It is not that the resentment would necessarily be misplaced - and I do not mean to suggest that Rabbi Shapira in the Warsaw Ghetto argued for turning the other cheek or forgiving one's oppressors. But where one can do nothing to change the venom or hurtfulness of others, what one can do - and it is a valiant and heroic feat - is avoid internalizing the venom, and refuse to make the hurtfulness a part of one's own self.

To quote the New York Times article of 1998 more fully: "'I had a murderous rage in my heart of Limerick, the humiliation of coming out of the slums,' [McCourt] says of his hometown in Ireland, the setting of his brother Frank McCourt's Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir, Angela's Ashes. 'It made you feel like nothing and there was no place to go but down. It was assumed we'd be low-class the rest of our lives. But who can you blame? Governments and churches that are gone now? It's useless. Let those things live rent-free in your head and you'll be a lunatic. Resentment is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die.'''

Where there is a lack of human goodness, exactly there it is most vital to practice humanity, an ancient rabbinic adage proclaims. And another observes that precisely where one perceives what may be divine fury and devastating power broken loose and raging unchecked in the world, exactly there one must work to manifest divine love and constructive possibility. And in the deepest sense, given the choice, for example, between Rabbi Shapira and the fearsome, relentless, all too successful persecutors he faced in the Shoah, whom do we today esteem to be the true giant?

In the story of our Torah this week, a whole generation of Israelites, who adopt the perspective of the discouraging ten scouts, are condemned to wander and perish in the wilderness, with only Joshua and Caleb, the optimists, surviving to enter the Promised Land.

That is a considerable bit more poetic and tidy than life often turns out to be.

However, the point that one's attitude can make a crucial spiritual difference, for oneself and those around and after one, and the message that what can endure and be worthy of continuing on is the uplift and encouragement one manages to muster and personify - these are observations every bit as true to life as are any objective assessments of the bleakest circumstances.

Exactly this brand of faith and trust - the refusal to become cynical and dispirited with regard to the miraculous light and the wondrous possibility within oneself and in those around one, be the surrounding circumstances what they may - says Rabbi Shapira, the Piasceczner Rebbe, the Rebbe of the Warsaw Ghetto, "brings near our salvation."