Peace builds in layers like a house of cards.

For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors hunted, gathered, and foraged for food. Extreme climates kept populations low--until everything changed 11,700 years ago. The planet warmed. An ice age ended, and Earth entered the Holocene.

Planetary conditions build the first layer in the house of cards.

A mild climate and nutrient-rich soil created a Goldilocks zone for agriculture--not too hot and not too cold. Our ancestors gradually traded hunting and gathering for livestock and crops.

Resource consumption adds a second layer to the house of cards.

How do you stop a neighbor from slaughtering your family and stealing your goats? Retaliation. If you kill one of us, we'll kill one of you. An eye for an eye. A tooth for a tooth. In this system, a human will probably kill you or someone you love.

Slowly--ever so slowly--farming communities coalesced into cities and states. Social and political frameworks emerged. Education and health care prevent most violent crime in Copenhagen, for example. If someone's murdered in Copenhagen, kinfolk don't kill the suspect's family in a midnight raid. They call the police. In this system, it's far less likely that a human will kill you or someone you love.

Civilization forms the third layer in the house of cards.

When governments are unstable or ineffective, warlords reign. We're horrified by ISIS beheadings when we see them on TV. But notice the shift. Most of us have only seen beheadings on TV; we don't walk past beheadings every day on our way to work. That's new in human history.

A slow grind toward peace forms the top layer in the house of cards.

Steven Pinker explains this trend in his book, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. The facts are clear. Per capita violence has been thinning for thousands of years.

Here's the problem: every day--bit by bit--we're undermining the structure that props up peace.

You're hungry after work, so you drive through McDonald's.

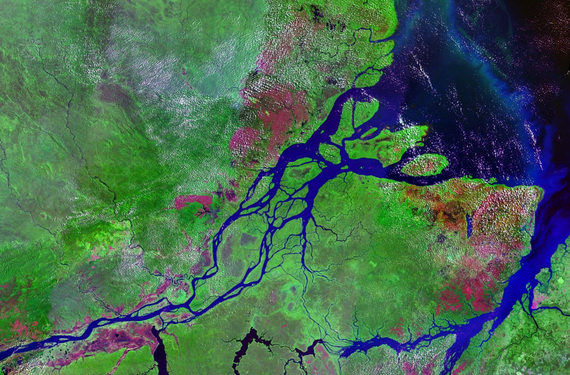

One pound of beef takes seven pounds of crops to feed. Those crops need land to grow, so we clearcut forests. Since 1970, the cattle industry has been responsible for 91% of deforestation in the Amazon. One of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth is disappearing, so we can plant crops to feed cows to feed humans.

Each pound of beef requires 1,847 gallons of freshwater. Cows fart methane, which catalyzes climate change 35 times faster than carbon dioxide. After the slaughter, beef patties burn fuel to pack, freeze, ship, and reheat. And then your car belches greenhouse gas as it idles at the drive-through window.

This style of consumption sucks resources from the Earth, builds products, and dumps waste. The process is linear. At the end of the line, waste--like the hamburger wrapper and greenhouse gas--doesn't biodegrade. It accumulates. It accumulates on land. It accumulates in water. It accumulates in air.

Ecosystems are different. A plant absorbs sunlight. A deer eats the plant. When the deer dies, bacteria chew her body into soil. Soil helps plants grow. The process is circular. Ecosystems waste nothing.

The planet could absorb small scale waste from early farming communities. The United States alone slaughtered 30.2 million cows last year. No ecosystem can absorb that hit.

This style of consumption--not simply overpopulation--strains the planet. The average USAmerican consumes the same amount as 370 Ethiopians. As poor countries gain wealth, they tend to consume more and more like USAmericans.

Some think this problem will solve itself. Cities burn dirty fuel, for example, until smog is thick enough to blot the sky black. People pass clean air legislation when they feel smog coating their mouths and throats and lungs. Wait a few hundred years, and discomfort will force us all to fix our habits.

Unfortunately, we don't have that kind of time.

With few exceptions, extinction rates have stayed roughly constant for 3.5 billion years. Extinction's now moving 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than normal because of our consumption. E.O. Wilson estimates half of all species will go extinct by 2100.

This is already the bloodiest century in human history. It's just not human blood.

Yet.

Peaceful civilizations take a long time to build, but they fall apart fast. They need agricultural resources and a healthy planet to support them from below. Destroy the planet, and the top layers collapse.

A drought hit Syria in 2007. The region, called the Fertile Crescent because of its crops, grew steadily hotter over the century that preceded the drought. Wind used to move moisture inland from the Mediterranean Sea, too. But that wind stopped blowing. Soil baked and cracked.

Researchers explained these changes in a PNAS study. "No natural cause is apparent for these trends," they write. The heating and drying trends do fit, however, with computer models of human greenhouse gas emissions. Our waste supercharged that drought. It was the worst on record.

The drought lasted three years. The Syrian government squandered resources. Crops failed. 1.5 million people were displaced, fueling regional conflict. Flimsy social and political frameworks rocked and swayed on a shaking planetary foundation.

Then everything crashed. Civil war erupted, and ISIS warlords took cities like Raqqa.

ISIS is complex, but one thing is clear: planetary change helped fan that pocket of violence into flame.

Two years ago, Solomon Hsiang and his colleagues analyzed 60 studies on climate and conflict. In "small-scale interpersonal aggression or large-scale political instability, low-income or high-income societies, the year 10,000 B.C. or the present day, the overall conclusion is the same," they write. "Episodes of extreme climate make people more violent." If trends continue, they project war could increase by 50%.

Last year, the Pentagon called climate change an "immediate risk" to national security for the same reasons:

Rising global temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, climbing sea levels, and more extreme weather events will intensify the challenges of global instability, hunger, poverty, and conflict. They will likely lead to food and water shortages, pandemic disease, disputes over refugees and resources, and destruction by natural disasters in regions across the globe.

The report continues by outlining new military strategies for a dying planet.

The problem's not hypothetical. It's not going to happen someday. It's real, and it's happening now. Some of us haven't felt the effects yet, but we will.

So how do we stop the bloodiest century in human history?

We change our habits.

Every night, the Fog-Basking Beetle crawls to the top of a sand dune. Its shell cools slightly compared to the air around it. Moisture from the breeze condensates on its back, and bumps roll droplets into spheres. The beetle tilts its shell, and water wicks into its mouth.

The Sahara Forest Project built greenhouses that mimic that beetle's morphology. The buildings pull water from thin air in the middle of the desert. Architects added solar power, too. Solar heat evaporates water and boosts crop productivity. Under the solar mirrors, they planted more crops that don't like direct sunlight. The project wastes nothing--not even shade.

We can map that concept onto our own, daily lives. Waste nothing. Every small step--recycling, composting, walking instead of driving, turning off lights when leaving a room--wastes just a little bit less.

Agriculture, manufacturing, shipping, energy, and transportation need overhaul, too. They might seem too big to budge, but we have a trump card: our habits control their profits. We can divest from destructive supply chains, innovate sustainable alternatives, and demand policies with teeth. Our decisions define these industries. Our habits can catch the house of cards mid-collapse.

Mass extinction might seem unavoidable; murder, war, torture, and terrorism might seem inevitable.

They're not.

We're living in the bloodiest century in human history, and our own, daily habits are to blame. That's good news. It means we can do something about it.