The new documentary How to Survive a Plague follows the rise and accomplishments of ACT UP, a political advocacy group that formed spontaneously in 1987 out of frustration and anger that both state and federal governments had done so little to address the AIDS epidemic that had already killed almost half a million people in six years. Through a mix of activism and diplomacy, not only did ACT UP become a vital voice for AIDS awareness and gay rights, but by members educating themselves about pharmaceuticals and the nature of HIV/AIDS, they were able to pressure and help the FDA and NIH to speed the development and approval of effective AIDS drugs in a way that changed the way drugs of all kinds are developed, tested, and distributed. Watch the trailer for How to Survive a Plague below.

One of the most striking things about How to Survive a Plague is that, aside from some interviews, the movie is almost entirely made from archival footage that was filmed in real time at meetings, demonstrations, and actions that document ACT UP's history as it was actually happening. The footage was shot by both professional and amateur camera people who had embraced a technology that had only recently come on the market: the video camera. With so much primary source material, it's hard not to feel that How to Survive a Plague is the definitive film on how the tide turned in the battle against AIDS, reigniting the gay rights movement and prolonging the lives of millions dying of HIV/AIDS while modernizing the way drugs are developed and approved in a way that has saved the lives of millions more.

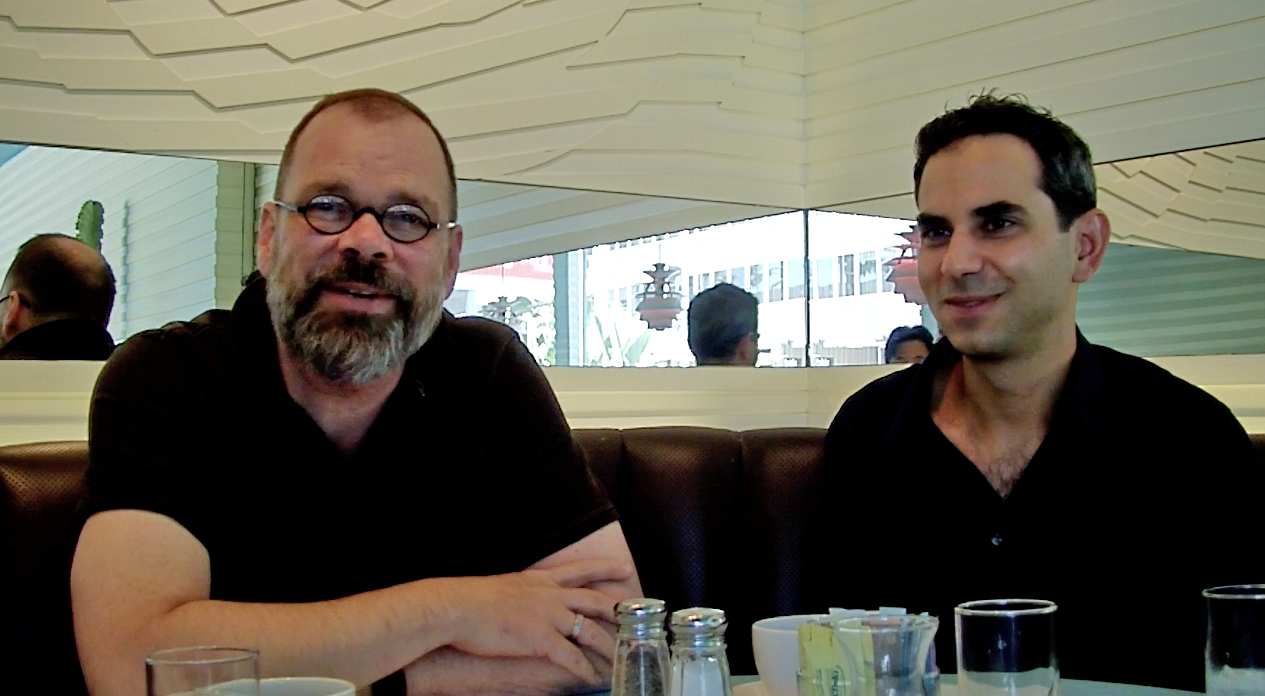

Last week I had a chance to interview the director of How to Survive a Plague, David France, and one of the film's producers, Howard Gertler, about the film, as well as about ACT UP's legacy. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

David France and Howard Gertler

Jonathan Kim: With ACT UP coming into existence with the AIDS crisis, is it fair to say that AIDS, in a tragic way, was sort of like the Stonewall of a new generation of gay activists?

David France: AIDS activism really is Stonewall 2.0. It took the beginning of a movement like Stonewall, which came in 1969 and spent about 10 years before the AIDS crisis establishing institutions, in the sense of what was the agenda for the gay rights movement. And then AIDS hit in 1981 and really found a community that was still very isolated and gave power and urgency to the movement in a brand new way. So the transformation that was brought on by ACT UP and by AIDS activists really began to fulfill the promises of Stonewall in a real and lasting way.

JK: I was just a kid when the AIDS epidemic was starting, and I felt a bit embarrassed that I really didn't know how bad things were in New York at the outset. Are you finding a lot of surprise about that, particularly in the gay community?

DF: Absolutely. It really is hard to remember how hideous things were and how far away from any sort of true citizenship gay people were by the time this major health disaster struck the community. And a lot of that is good. It's good that we don't remember the darkness, in a way, because we've done away with that through AIDS and AIDS activism. The LGBT community established their position in society in kind of a permanent way and really transformed that. It really is hard to remember that when AIDS hit we just didn't have role models in any way. We really didn't have any actors, for example, who were out of the closet. There were no out politicians, there were no out journalists -- none in 1981. To imagine that today is almost impossible. But the story is important to remember not just because it shows the power of the community to have made that transition, but because it shows that those types of transformations are possible. Really fundamental change, even in the worst circumstances, is possible. Triumph out of the burning flames of an epidemic is possible.

JK: One of the striking things in the film is the legacy ACT UP left in the way drugs are developed and approved, and not just drugs for AIDS.

DF: The biggest impact of AIDS treatment activism -- besides having helped find, identify, create, test, release, and market these drugs that saved millions and millions of lives -- was to recreate the American health-care system to make it possible to bring new and experimental drugs that prove efficacious to market in rapid time. Before ACT UP, it took 10 or 12 years for a drug to go from an idea to a medicine cabinet. That may have seemed appropriate before, but in a disease state where the average life span after diagnosis was just 18 months, there was not time for that sort of laconic, studious, almost academic approach to finding the answers about a new compound. And what ACT UP innovated, and what they left behind as a lasting legacy, is an approach to understanding new drugs that allows you to figure out how efficacious they are not in a dozen years but in two years or less. And that has been a benefit for all disease states, for breast cancer, for colorectal cancer. Any area of research today is enjoying the benefits of this new world that was invented by these total outsiders, people whose only experience with the scientific world was having been diagnosed HIV-positive.

JK: You mentioned in an interview that ACT UP and the AIDS movement really deserve a place in the history of civil rights. I know there aren't perfect comparisons, but is there something analogous in the civil rights movement that you'd equate to what ACT UP did?

DF: I guess there's two answers to it. Think about Rosa Parks, someone who was drafted into heroic action by immediate circumstances and who touched off a revolution. And we see that in How to Survive a Plague, where the people weren't scientists; they weren't activists to begin with. They were ordinary young people hoping to live ordinary lives, and they found it impossible because of the arrival of this epidemic. So they were drafted into it, and they found a way to also play heroic roles and to transform society, certainly as profoundly and fundamentally as the civil rights movement had before them. And another answer is really about the movie itself. I think that historically, the film Eyes on the Prize really, finally, and once and for all, established the civil rights movement as being a profoundly American movement that created the America that we know and convinced people -- myself included when I first saw it -- that the civil rights movement was part of my inheritance as an American. And that's what we wanted to do with How to Survive a Plague, to show the equal power of both movements and to really place them in the context of American history. AIDS activism is a chapter in our national past that we have all benefited from and that we should all embrace for the gifts it left behind.

JK: When you were deciding to make this film, did you think you could do it almost exclusively with archival footage? I was not expecting that at all, and it seems pretty audacious to think you would be able to get all that footage to tell the complete story.

Howard Gertler: It was an hypothesis at first. It was something we thought should be possible, and something we discovered over the course of looking through the footage. A lot of the people we got the footage from were shooters, videographers, and filmmakers themselves. So whether we were getting it directly from them or from their estates, these were all people who knew how to tell a story through camerawork, and you would have more than one of them covering any one action or demonstration. So we had this trove of coverage, and when do you actually get coverage for an historical documentary? It almost never happens. We were lucky how these filmmakers knew they were preserving their own work for posterity.

DF: We wanted to give the viewer the visceral feeling of what it was like back then. And that's why we worked so hard to amass all that footage, enough so we could tell this epic, 10-year story as though you were watching it unfold the first time. Watching the film is almost like watching a documentary made years ago that we found on a shelf someplace. It's not a story of people sitting in front of their bookcases remembering what it was like back then. It's people experiencing it firsthand as it's unfolding.

JK: I think a lot of people think the age of video activism started with Rodney King and now has fully come about with smartphones, but your film really shows that the AIDS epidemic is where it starts.

HG: The rise of ACT UP and AIDS was concurrent to the rise of prosumer video cameras, and every standard-definition format that ever existed is in the film. During the time period that we followed, people didn't have access to this footage. So what I knew about ACT UP was what I saw on the news, and as we show in the film, the news coverage was very, very glib, and it portrayed them as disrupters (which they were), brilliantly and theatrically being troublemakers. But they were also brilliant infiltrators and diplomats in the work that they had to do to cobble together the alliances to get the drugs out there.

JK: You mentioned how brazen anti-gay hate was at the time, and that reminded me of a part in How to Survive a Plague where they mention gay people being beaten up in hospitals.

DF: For being gay. Beaten up by guards in hospitals for being gay, having gone to the hospitals for health care because they were sick. Those early years were amazing. The film starts in 1987, but it was still bad. But in 1982 and 1983, patients were being refused access to hospitals, or they were being checked into rooms and never visited by anybody. And I was a journalist at the time, and I was getting calls from people saying, "I'm in the hospital, and I haven't been given a tray of food in two days." And you would go to their rooms, and you'd see their trays sitting outside the door, where they had been dutifully dispensed but not actually delivered to the patient. What that was telling us at the time were that gay people were not even thought of as human, and certainly not deserving of any of the most fundamental things that humans could expect, like compassion or empathy.

JK: A lot of times in stories about activism you see their setbacks and battles lost, but I was really struck when the film discusses how ACT UP's whole strategy might've been wrong in terms of trying to rush drugs into circulation before it was sure if they worked or not. I was wondering what your thinking was for why you felt that was such an important thing to include.

DF: This is a story of heroic work. One of the most difficult things to do, and probably the most heroic, is to assess your own work and be honest about whether it was the right or wrong thing to do. And I was really taken by that juncture in this history where the activists who we've been following for two thirds of the film suddenly realize that they had created a system that wasn't really working. It was getting drugs out quickly, but it wasn't getting the good drugs out; it was getting the bad drugs out. And that getting those bad drugs out was doing a disservice and doing some harm to people living with HIV, and it was undermining the research technicians and making it really impossible to know if a drug was or wasn't working. And they were so painfully honest and apologetic at that juncture and knew that they had to reassess the standards that they'd established and had to come up with one that would actually work. And that change in any movement, to say, "We made a terrible mistake," and to not walk away and to stay in the fight and to reappraise, re-evaluate, and then to re-create and re-establish, is just really one of the most powerful moments, I think, in this story.

* * * * *

How to Survive a Plague opens Friday, Sept. 21, in Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, and Chicago. To find out if/when it's playing near you, how to support the film, and to learn more about the fight against AIDS, go here.