Donald Trump delivers his victory speech on November 9, 2016

Donald J. Trump is the president elect. In a few months, he will be sworn in as the 45th president of the United States. The media pundits are flabbergasted by his electoral triumph. Having repeatedly written him off, his improbable success on election night is inexplicable.

What exactly does Trump's electoral victory signify?

The liberal media has been quick to characterize the Trump victory as the last gasp of an angry white tribe lashing out in a final act of defiance against the demographic forces that are slowly changing the complexion of the U.S. electorate. To the left, Trump's victory is nothing less than a racist repudiation of the legacy of Barack Obama, America's first African-American president; a xenophobic defense of white privilege by a class that sees its political and economic power slowly and inexorably slipping away forever.

Indeed, the media largely portrayed the campaign in racist and misogynistic terms. To them, Trump was a candidate that routinely demeaned and insulted women and minorities, showed no respect for due process of law, and cultivated fear and hatred to mobilize his base. When Hillary Clinton referred to his supporters, "as a basket of deplorables," the media didn't criticize her; they largely agreed that her characterization of his base as sexist, racist and misogynistic was consistent with their description of his campaign.

The difficulty with this narrative is that the exit polling indicates that these issues didn't weigh very heavily on the electorate. Trump did far better with women and Hispanics than the polls had predicted; and while the African-American vote broke overwhelmingly in favor of Hillary Clinton, Trump got a much higher percentage of that vote than Romney got in 2012.

There is, however, another way of characterizing this election, not in terms of xenophobia and race, but in economic terms. On November 8, an increasingly displaced blue-collar working class, a group ignored by both the left and the right, voted for their pocketbook. Their repudiation of President Barack Obama's legacy was not motivated by race but by the ineffectiveness of his policies. The aggregate economic indices notwithstanding, those policies have not eased the plight of the working class. They have not created more employment for them or improved their wages.

The 2016 presidential election was a populist election. Only a populist could have won it. The Republicans, to the consternation of the establishment nominated a populist. The Democrats, to the relief of the party elite, at least initially, opted against their populist. Whether Bernie Sanders could have defeated Donald Trump will never be known. The post mortem "what if" polling is about as useful as the polls that showed Hillary Clinton winning in a landslide with a 12-point margin. A Sanders-Trump election would have been a fascinating political drama, one that would have produced a very different political alignment.

I must give credit to Michael Moore, who called the election while most pundits were still debating the size of the anticipated Democratic landslide. I can't say that I agree much with Michael Moore, but I still respect him and his work. Yes, you can respect someone with whom you usually disagree. In the old days, we used to call this civil society. Unfortunately, it's all too rare these days and virtually extinct on college campuses. I'll even buy Michael a cup of coffee next time he is in Portland and give him a chance to explain to me why I am wrong on just about everything.

Hillary Clinton campaigning in Tempe Arizona, November 2, 2016. Photograph courtesy G Skidmore

Donald Trump is an unlikely populist. It is ironic that a New York billionaire real estate developer would succeed in convincing America's blue-collar workers that he could be their champion and that he could restore their economic well-being. The challenge now will be to deliver on that promise. The economic dislocations transforming the blue-collar working class are not going to be reversed with a bully pulpit, the threat of higher tariffs on imports or tearing up free trade agreements.

Increasingly, in the Western world there are two different economies coexisting, the manufacturing based economy of tangible things and the digital economy of intangible products. Both economies have always existed, but of late employment in the intangible economy has been accelerating, while employment in the tangible economy has been shrinking. That development is driving a long-term political realignment in the Western world.

Take North American manufacturing. In the last two decades, this sector has lost over six million jobs; about one-third of manufacturing employment. In that same period the total economic value of manufacturing output increased by roughly 50 percent. Two-thirds as many workers produced 50 percent more than their fathers did. Nor are these types of economic trends unprecedented. A century ago half of all workers were employed in the agricultural sector. Today only about one percent of workers work in agriculture, while output has increased more than twenty-fold.

Globalization has seen governments around the world band together to create larger "free market" economic zones, like the European Union (EU) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), while simultaneously encouraging the free flow of labor/migration and capital around the globe. Seamless global supply chains, the impact of digitization, and cheap, instantaneous communications and data sharing has further encouraged this trend by making geography less of a limiting factor of commerce than it used to be.

The problem with globalism as an economic strategy for maximizing output and economic growth is that the costs and benefits of globalism fall disproportionately on different socioeconomic groups. Those economic sectors that decline, in North America and Europe these are principally lower skilled industrial manufacturing jobs, create unemployment, social and personal turmoil, and declining property and asset values, not to mention that they devastate those communities that are overly dependent on the industries affected.

Neither the Democrats nor the Republicans have dealt with this issue. Instead all Washington has been willing to do is to liberalize food stamp benefits and increase the term for unemployment insurance. The working class isn't looking for more food stamps and more unemployment benefits, what they are looking for is meaningful work they can be proud of. Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders understood this. All the other candidates and the national media missed it.

Long-term these jobs would have disappeared anyway, but the economic, trade and foreign policies that encourage globalism invariably makes this happen faster. In turn this breeds resentment against the most visible manifestations of globalism, international capital, trade agreements and migration, both legal and illegal. Nor is globalization entirely at fault. Computer technology, inexpensive chips and ever more sophisticated software have driven factory automation and also reduced manufacturing jobs.

Since 2008, employment growth in the intangible economy has been growing faster than in the tangible one. Such claims are controversial because there is no standard definition of what constitutes the intangible economy. Some definitions are very narrow, focusing primarily on the "digital economy," while others are more expansive and include any employment that is not devoted to making "things," and includes the service sector. Regardless of the definition, employment in the tangible economy has been declining while that in the intangible economy has been increasing.

Senator Bernie Sanders on the camapign trail. Photo courtesy of G Skidmore

These economic trends manifest themselves politically in the divergence over key issues between the tangible and intangible economy. For example, take energy and global warming. The manufacturing sector represents roughly one-third of North American energy consumption. Energy costs are typically one of the top three cost items in manufacturing. Such costs are less important to the intangible economy. Not surprisingly, voters in the intangible economy are more willing to replace inexpensive hydrocarbon energy with more expensive "green" energy than workers in the tangible economy.

Immigration shows a similar fault line. Workers in the tangible economy see increased immigration as a competitive threat to their employment and wage prospects. In the intangible economy, immigration is a source of highly skilled and educated workers and cutting-edge knowledge.

The debate over globalization has a similar division. In the tangible economy, support for free trade is inversely related to an industry's global competitiveness. The North American aerospace industry, for example, is cutting-edge and strongly supports free trade. The steel industry, on the other hand, often burdened by significant legacy costs and older technology, is far more protectionist. The intangible economy, not surprisingly, heavily dependent on scale, is far more supportive of free trade and globalization. This is especially true in the digital sector, where global distribution can be achieved with a mouse click.

The 2016 presidential election underscored the fact that the Democratic Party has emerged as the defender of the political and economic interests of the intangible economy, while the Republican Party has emerged as the standard bearer of the tangible economy. That's why Silicon Valley is a bastion of Democratic Party support and steel workers and coal miners increasingly vote Republican. It's also why those states where the intangible economy is growing rapidly, like California, Washington, Massachusetts, North Carolina or Colorado, are increasingly Democratic or have shifted from reliably Republican to swing states, while normally dependable Democratic states like Wisconsin and Michigan flipped Republican.

Blue-collar jobs are going to decline because the long-term economic transformation that is driving that trend will continue regardless of who occupies the White House. Moreover, protecting legacy industries risks holding back the cutting-edge industries of tomorrow. The challenge is to provide meaningful employment for displaced workers while still maintaining an economic environment that allows the innovative industries of the digital economy to flourish. Unfortunately, the Facebooks and Apples of the world that define our economic future have little need for unemployed coal miners and steel workers.

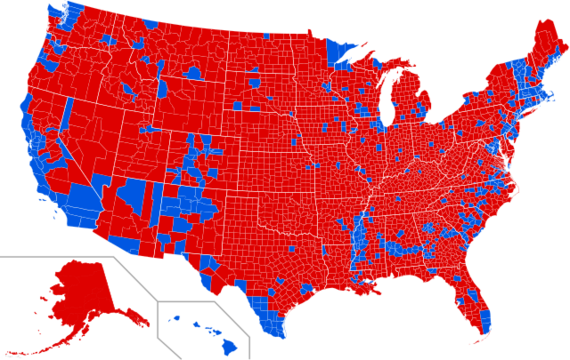

There are a few other conclusions that can be drawn from the 2016 electoral results. The great Roosevelt coalition that heralded the rise of the Democratic Party to national power is on its last legs. One-by-one, the pillars of that coalition, the elderly, rural households, southerners, industrial blue-collar workers, have peeled away. All that's left now is the urban centers and their inhabitants. A map of voting patterns by county is instructive-population dense urban oases of Democratic blue surrounded by a never-ending sea of Republican red.

Presidential election results by county. Democratic majorities in blue and Republican majorities in red. Image courtesy Ali Zifan

The challenge for the Democratic party is to decide whether it should embrace the "progressivism" of the Bernie Sanders-Elizabeth Warren wing of the party and try to re-establish its credibility with America's industrial working class or whether it should put all its chips on the electorate of the digital economy. The latter represents its strongest long-term prospects, but at the risk of becoming a bi-coastal party with a much weaker political hand in the short-term as the shift in industrial and blue-collar workers turn reliably Democratic states in the Midwest into swing states if not Republican bastions.

The Republican Party is now the party of the blue-collar working class, having transformed in two generations the most stalwart of the Democratic Party's base. Should that trend continue, then the Electoral College map will undergo a tectonic shift, one that will eliminate the inherent advantage that Democratic candidates have enjoyed for the last half dozen election cycles. These short-term gains, however, come at the price of aligning the party with those economic sectors that will continue to be in a long-term decline. Incidentally, it also means that there is a fundamental disconnect between large segments of industrial union's rank and file and their pro-Democratic party union leadership.

Finally, the outcome of the election underscored the growing irrelevance of the national media. The issue is not just that the media got it wrong, it's that a large portion of the country, what liberals contemptuously dismiss as "fly over country," couldn't care less what the national media said or their characterization of the campaign.

Hillary Clinton made Donald Trump's fitness to serve as president the central theme of her campaign and the national media seconded that decision. That's why it felt that the national media was so biased in favor of Clinton, for the most part the media simply echoed and amplified the Clinton campaign's narrative. Trouble was that the Clinton campaign was preaching to the choir. A significant number of Americans never bought into that narrative, enough to give Trump the victory on November 8.

A generation ago, Walter Cronkite's reversal of his support for the war In Vietnam meant that the Johnston Administration had lost the support of Middle America. Today, the only people who truly care what network anchors have to say are their adoring neighbors on the Upper West Side and their Beverly Hills groupies.

Even now, a week after the election, the national media still doesn't get it. Instead it seems determined to refight an election, that is now over and which it lost, by readdressing issues that the electorate has already dismissed as irrelevant. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the praise newspapers, like the Washington Post or the New York Times, heap on the rioters protesting Donald Trump's election victory or the prominence they give speculation on the inevitability of Trump's impeachment.

Had Hillary Clinton won the election and had it been Trump supporters rioting in the streets, they would have been branded as a proto-fascist mob and a threat to democratic order. Moreover, Trump would have been blamed for their violence and called upon to tell his supporters to go home.

Donald Trump campaigning in Phoenix Arizona, August 2016. Photo courtesy of G Skidmore.

Instead a bunch of coddled college students (I guess they are looking for a safe zone) and paid agitators are held up as an example of free speech and democracy in action. Why hasn't the national media demanded that Hillary Clinton tell her rioting supporters to stop destroying innocent people's property and go home? The hallowed distinction between the editorial page and the news pages has been forgotten. "All the news that's fit to print" has been replaced by "all the news that's fit to spin."

As for the Clintons, well I suppose they will just fade away into obscurity, sort of, and defend their ill-gotten gains. There's still money to be made preaching to the liberal choir, although I doubt anybody will be paying Bill Clinton million-dollar speaking fees to pontificate on the state of the world.

The Clinton Foundation can forget about all those fat foreign donations. The problem with a quid pro quo is that you need a quid to get a pro. None is available now, at least not until Chelsea runs for Congress. Sorry America, the Clintons aren't done with you yet. Still the next generation of Clintons may be better than the first. Hard to see how they could be any worse.

One week into a presidential transition isn't much of a track record. Still, President-elect Trump is showing himself to be open minded and willing to listen. I've had my differences with Trump's policies, but I'm encouraged by what I see. I think he has the potential to be a pretty good president. There will be plenty of things on which to disagree with the Trump Administration in the future but for now Hillary Clinton's supporters and the national media owe it to the country to give the man a chance.

Donald Trump was an unlikely candidate who has emerged even more improbably as the champion of the working class. His task now is to ensure America's long-term economic prospects while protecting those workers least able to adjust to that economic future. How this task is to be achieved, indeed whether it is even achievable, will define his presidential legacy.