The Battle of Loos

The Battle of Loos was the largest, most extensive British engagement on the Western Front in 1915. It was the first time that units of "Kitchener's New Army," were deployed in battle. These troops were part of the all-volunteer army that had been organized, on Kitchener's recommendation, to replace the troops lost by the virtual destruction of the British Expeditionary Force in France in 1914. At the time, Kitchener was the Secretary of State for war. Loos also marked the first time that the British Army would use poison gas on the battlefield.

In September 1915, in what the Allies would later call the Third Battle of Artois, and the Germans the Herbstschlacht or "Autumn Battle," British and French forces launched a broad offensive that simultaneously attacked German positions in Champagne, the Ardennes, and Artois. The main objective of the campaign was to capture the railways at Douai and Attigny and force the Germans to withdraw from the Noyon salient.

As the French mounted an attack in Champagne, the British, on their flank, were also in action at the Battle of Loos. The assault, commanded by Field Marshal Douglas Haig, despite his misgivings and those of the British Commander in Chief, Sir John French, about the timing of the venture, was preceded by four days of artillery bombardment during which a quarter of a million shells were fired. Despite the extensive bombardment, Haig had been hampered by a shortage of artillery shells so the resulting bombardment fell far short of what he had originally planned. Six divisions were committed to the attack on September 25.

Haig was convinced, despite the lack of success of mounted troops to date, that the British cavalry could be used to exploit any breakthroughs in the German line. He kept in reserve his Cavalry Corps and the Indian Cavalry Corps. He also had in reserve the XI Corps. The XI Corps consisted of the 21st and 24th Divisions of the New Army and the Guards Division. The 21st and 24th Divisions had just recently arrived in France and the staff of the XI Corps had not previously worked together.

As in previous British engagements, Haig deployed Royal Engineer tunneling companies to dig tunnels from the British lines under no man's land to the German lines in order to plant explosive charges, "mines," under the parapets of the German front line trenches. The British attack was timed to begin with the detonation of those charges.

British forces had a significant numerical advantage over their German enemies; in some places along the front they outnumbered the German defenders by seven to one. They had another advantage; German gas mask design was deemed too primitive to cope with the 140 long-tons, 308,000 pounds, of chlorine gas the British were to use against them. As at Ypres, however, the prevailing winds shifted from time-to-time, ensuring that the gas affected both sides. Although only seven British troops died from gas exposure, there were more than 2,500 casualties.

At the southern end of the attack, Haig's forces met with success on the first day, taking the town of Loos (which was eventually completely destroyed) and progressing towards the city of Lens. The insufficient artillery bombardment, however, meant that the barbed wire obstacles and mine fields in front of the German positions had largely remained intact. Advancing in narrow columns against the German lines, British troops were particularly vulnerable to German machine gun fire. Although the British were successful in overwhelming the German lines by sheer weight of numbers, the resulting casualties were horrific.

Problems with supplies and the need for reserves brought that day's advance to a halt. Elsewhere, the British gas attack was less effective, even though two divisions managed to gain a foothold on the Hohenzollern Redoubt.

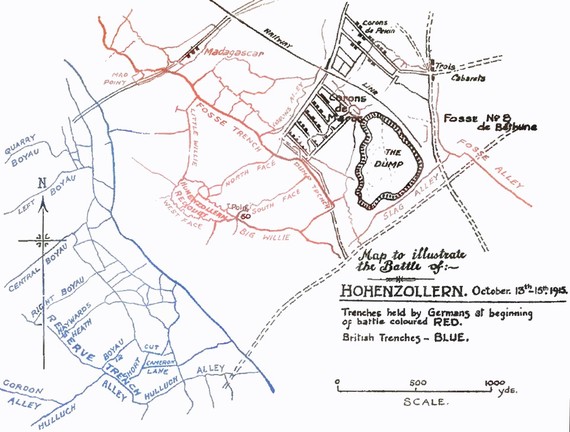

British (blue) and German (red) trench lines at the Hohenzollern Redoubt, Battle of Loos October 13-15,1915

British (blue) and German (red) trench lines at the Hohenzollern Redoubt, Battle of Loos October 13-15,1915

Due to the shortage of artillery shells, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd wings of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) were deployed to identify targets for the artillery prior to the battle in order to insure that shells were not wasted. Equipped with new wireless transmitters, the pilots were able to direct British artillery fire on German targets. This was the first time that air forces had been used in this way.

As the battle progressed, the RFC was used to carry out tactical bombing operations. Armed with 100-pound bombs, aircraft from the 2nd and 3rd wings of the RFC attacked German troop concentrations, both on the front lines and those in reserve formations, as well as trains, rail lines, and marshaling yards. This was the first time that air power was deployed in close ground support of advancing troops.

The following day, having brought up reserves, the Germans counterattacked in force. The British, also attempting to attack, and with no preliminary artillery barrage to support them, found themselves again advancing into withering machine gun range without any covering fire or moving artillery barrage to support them. After a few days of on-off engagements, Haig's troops were ordered to retreat on September 28.

A further attack which began on on October 13 was called off when heavy losses and poor weather made defeat inevitable. The number of casualties were staggering: 50,000 on the British side, perhaps half that number of Germans. Loos was a complete failure. One additional consequence of the Battle of Loos was that it contributed to the replacement of Sir John French by Sir Douglas Haig as British Commander-in-Chief later in 1915.

Haig, a member of Scotland's Haig & Haig whisky distilling dynasty, would command British troops on the Western Front for the balance of the war. His single-minded determination and his seeming obliviousness to his troops' losses would make him a controversial figure in the British conduct of the war and earn him the disparaging epithets of "Butcher Haig" and "The Butcher of the Somme."