Gallipoli: The Ground War

By the beginning of June 1915, the stalemate that had ensued in the Gallipoli campaign prompted Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, to decide to commit even more troops to Gallipoli. In Britain, still without conscription, a new campaign to enlist more troops was initiated. In June and July 1915, almost 50,000 fresh troops were sent to reinforce the 80,000 already in the Dardanelles.

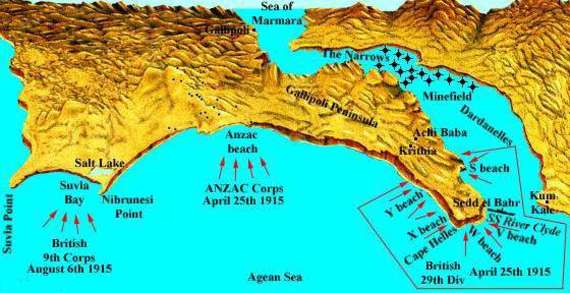

The stalemate dragged on into the summer as Allied troops suffered in the scorching heat and disease-ridden conditions. In July the British reinforced the bridgehead at Anzac Cove. The following month, on August 6, 20,000 fresh reinforcements attempted to seize the Sari Bair heights by landing troops at Suvla Bay, to the north. The plan was to drive across the peninsula and cut off Turkish forces in the South. In the face of Ottoman counter-attacks, the initiative failed within days.

The landings on Suvla Bay marked the start of a general offensive by the Allied troops to break out of their beachheads. Commanded by Mustafa Kemal, Turkish reinforcements were brought up and thrown into the battle, and once again the Allies failed to make any significant advances. The casualties were terrible. The Allies lost over 45,000 men in the first ten days of the offensive. Ottoman losses were almost 40,000.

In mid-October, Kitchener replaced Hamilton with Lt. General Sir Charles Munroe. He immediately recommended to Kitchener a complete withdrawal from Gallipoli even though, he believed, it could cost another 40,000 casualties to do so. Following a personal inspection by Kitchener in November, the order was given to withdraw.

The troops were evacuated by the end of January 1916. Despite pouring in half a million men, the Allies had been unable to take the south of the Gallipoli peninsula and link up their beachheads, let alone march to Constantinople. Allied forces had suffered over 250,000 casualties of which 50,000 had been killed. Turkish casualties were between 250,000 and 350,000. A final potential catastrophe was averted. Over 119,000 men were evacuated safely. Turkish soldiers, refusing to attack, just let them go.

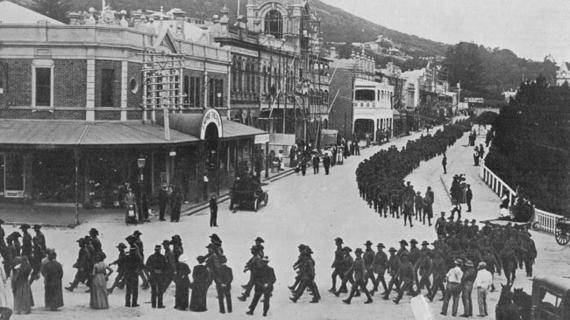

There was one other consequence of the Gallipoli campaign. It was there that the legend of the Anzac's would be forged. Approximately 17,000 Australian and New Zealand troops had landed on the Aegean side of the Gallipoli peninsula in April of 1915.

They were called the "Anzacs", short for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps. British Military planners, too lazy to keep writing out the full name, had conveniently shortened it to Anzac. It was as the Anzacs that they would fight in the suffocating heat and the wretched, stinking conditions of Gallipoli and it was as the Anzacs that they would pass into history and into legend.

They came as "Empire Men", loyal members of a British Empire that then spanned a quarter of the globe. Few had ever seen the mother country, most never would, but they were the products of its culture, its heritage and its institutions. When king and country called, they answered by the thousands. Almost half a million Australians and New Zealanders would ultimately see action in the Great War. They would fight and they would die. At Gallipoli two out of every three Anzacs would be killed or wounded fighting in a war they did not start, for a mother country they had never seen.

It was at Gallipoli that they would begin to forge a national identity. They may have come as "Empire Men," but they would leave with a budding consciousness that first and foremost they were Australians and New Zealanders. It was also at Gallipoli that a young Australian journalist named Keith Murdoch, the father of media tycoon Rupert Murdoch, would achieve international fame for his account of the military bungling that characterized the campaign.

In the end, militarily, the Gallipoli campaign achieved nothing. The Ottoman Empire was not knocked out of the war. The Turkish military proved itself to be far more formidable, especially in a defensive role, than it had been given credit for. No new lifelines to Russia were established, the Eastern Front was not expanded and the stalemate between the two sides continued.

Encouraged by the Ottoman success, Bulgaria declared for the Central powers. Greece, in order to avert an attack from Bulgaria, promptly joined the Allies. The only thing that did change was the continuing and ever escalating toll of casualties. When it came to the body count, there was no stalemate.