Last Wednesday, my organization, Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, filed Federal Trade Commission complaints against two leading developers of apps for babies. These complaints are the latest in our ongoing advocacy to stop the false and deceptive advertising of baby media; our prior efforts led Disney to offer Baby Einstein refunds and to a landmark judgment by the FTC against Your Baby Can Read. Consumer protection laws require that companies substantiate any educational or cognitive claims that they make about their products. Both Fisher-Price and Open Solution claim their apps teach babies language and math skills, but cite no research to back up these claims. And there is no credible research that any form of screen media is an effective tool for teaching babies. That's why we've been so vigilant about calling out baby media companies that make educational claims.

CCFC doesn't think companies should be allowed to deceive parents and, if the feedback we've gotten so far is a good indication, most people agree. But not everyone is a fan. At Slate, Hanna Rosin railed against CCFC's "absurd war on technology for kids." The oft-stated goal of our ongoing baby media campaign is to make it easier for parents -- who are operating in virtually uncharted territory when it comes to the newest technologies marketed for young children -- to make informed decisions. We welcome civil, fact-based, dialogue about our campaigns, but Rosin's piece contained enough inaccuracies that it may make things even more confusing for parents -- and therefore warrants a response.

First of all, I was a tad surprised to learn we were at war. CCFC is in no-way "anti-technology." We do support the American Academy of Pediatrics' recommendation to discourage screen time for children under two, and, like the AAP, we believe that some time spent with quality media can play an important role for older kids. But when FTC complaints and expressed concerns are turned into "wars," the real story often gets lost. So for the sake of clarity, here are five things you should know about CCFC's ongoing campaign to hold the "genius baby" industry accountable.

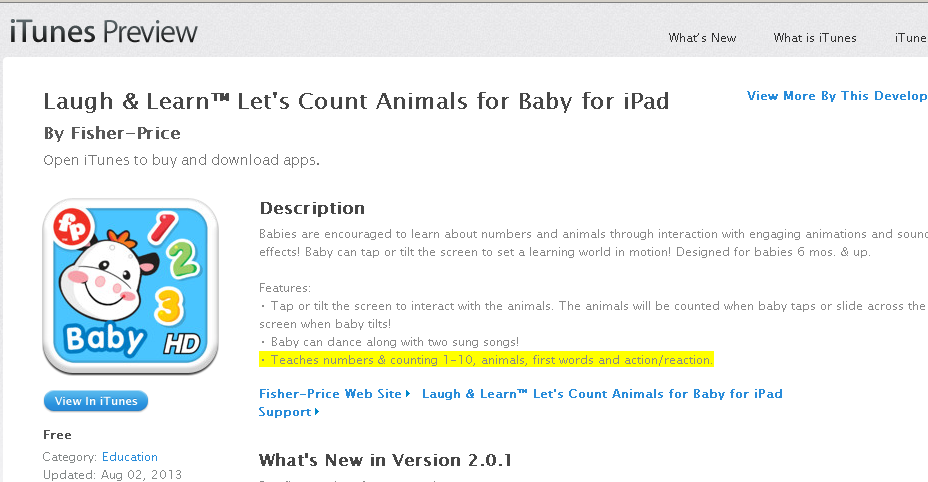

1. Both Fisher-Price and Open Solutions make numerous educational claims that are not substantiated by research. Our Fisher-Price complaint cites seven of the company's Laugh & Learn apps and details the marketing claims for each app that aren't supported by research. These can be found both in the body of our complaint and in a handy appendix at the end. But Rosin omits the claims we detail in our complaint and instead selectively and deceptively discusses just one example of Fisher Price's marketing that we didn't mention! She writes:

The iTunes page for Fisher Price's Laugh & Learn counting app says, for example, "Babies are encouraged to learn about numbers and animals through interaction with engaging animations and sound effects," which, if you look at the app, they are. That doesn't mean they will learn their numbers or morph into Isaac Newton, but, sure, encouraged they may be.

Rosin neglects to mention that, on the very same iTunes page she links to, Fisher-Price claims that this app for babies as young as six months, "Teaches numbers & counting 1-10, animals, first words and action/reaction." Since teaching implies learning, it sure sounds like Fisher-Price is claiming babies will "learn their numbers."

All of the apps we cite from both companies make explicit educational claims. Open Solutions even markets its apps for babies as a "new and innovative form of kids' education," and says that babies will "learn how to read, pronounce and spell basic verbs."

2. Our advocacy is research-based. Rosin accuses CCFC of cherry-picking our studies.

News stories about this latest children's media war repeat the same claims that the CCFC made about Baby Einstein -- that studies have shown that children under 2 who are exposed to media develop ADHD or score lower on certain tests or are more likely to develop some kind of delinquency later in life. But those studies are highly disputed.

Since neither our complaints, nor the New York Times story she links to, even mention research linking media exposure for babies to ADHD or delinquency, it's hard to know what Rosin actually objects to. What we do cite is the opportunity cost of screen media for babies. Time spent with media takes "time away from activities, like hands-on creative play or face-time with caring adults that have proved beneficial for infant learning."

The other research we cite is the growing body of evidence that screen media -- videos, television, apps -- is not an effective tool for educating babies. Here, too, Rosin objects, conflating babies with older children. She says, "CCFC is exaggerating when they say there are no credible scientific studies that show kids can learn from apps." Our complaints, and the research we cite, focus only on babies and toddlers. If Rosin is aware of studies showing that apps can teach babies language and math skills, why isn't she citing that research in her post? We -- and I'm guessing Fisher-Price and Open Solutions -- would love to see it!

3. Our complaints are effective. Rosin admits that Baby Einstein's marketing was once "exaggerated" but claims that was during "the crude, early days of appealing to parental anxiety and ambition, and since then, companies have gotten more subtle and smart." But the companies CCFC targeted in the past didn't just become "subtle and smart" -- the FTC, as a result of our complaints, forced them to change their marketing because they were violating consumer protection laws. That's what we hope will happen to Fisher-Price and Open Solutions, both of which -- as our complaint amply demonstrates -- are hardly restrained in their marketing.

4. Cultural context can make deceptive marketing even more effective. "If parents ever believed that a baby watching shapes drift by on a TV screen was going to turn into Einstein," writes Rosin, "then they were willfully deluded." By shifting blame to parents, Rosin overlooks that the Baby Einstein brand was built in the late '90s, at precisely the time when brain development became all the rage in books and magazines about parenting. Baby Einstein exploited this trend by claiming, "According to cognitive research, dedicated neurons in the brain's auditory cortex are formed by repeated exposure to phonemes... Through exposure to phonemes in seven languages, Baby Einstein contributes to increased brain capacity." Since Baby Einstein was just making this stuff up, it seems strange and unfair to point the finger at parents.

Similarly, Fisher-Price and Open Solutions are marketing their apps just as tablets are being hyped as an educational panacea. The cash-strapped Los Angeles Unified School District is shelling out up $500 million to get every kid an iPad. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) is now encouraging preschools to incorporate screen technologies into their classrooms. This spring, a much-discussed story in the Atlantic (by Rosin) sung the praises of tablets for babies and kids of all ages. In this climate, parents don't have to be "willfully deluded" to believe what Fisher-Price and Open Solutions are claiming.

5. Media producers who can't substantiate their educational claims are violating existing consumer protection laws. Lost in Rosin's narrative of "media wars" is any discussion of the legal issues involved. But here's what the FTC staff wrote in response to CCFC's complaint against Baby Einstein and Brainy Baby in 2007:

Advertisers must have adequate substantiation for educational and/or cognitive development claims that they make for their products, including for videos marketed for children under the age of two; reliance on general theories of child development or on studies of products that are materially different from the advertised product will not be sufficient.

You'll notice that, from a legal standpoint, it doesn't matter whether parents are, as Rosin claims, complicit by believing false advertising. Companies, the law clearly states, are not allowed to deceive consumers.

CCFC is simply asking the FTC to hold Fisher-Price, Open Solutions and the growing baby app industry to the same standard as Baby Einstein. We're not, as some have accused us, trying to ban baby apps or shame parents who use them.

It's hard enough to raise young children in today's digital world without being bombarded with false advertising. It's wrong to exploit parents' natural tendency to want what's best for their babies. And it's against the law to make unsupported educational claims about any product.