Historical memories have been making a geopolitical comeback this year thanks to the 70th anniversary of the end of World War Two that has been commemorated from Europe to Asia. August 6, 1945 the first atomic bomb in world history was dropped on Hiroshima and three days later on Nagasaki. However, August 15, 1945, the day that Japan accepted unconditional defeat, has come to be remembered as one of the most consequential, albeit controversial, days of historical memory.

Asian victims of Japanese imperialism and militarism, particularly Chinese and Koreans, have used their own historical memories of Japanese wartime actions to create nationalist narratives that inform the current generation's demand for apologies on this particular day every year. Previous statements of apology by Japanese Prime Ministers like Kono and Murayama have seemingly fallen short because of their socialist center-left credentials compared to conservative center-right nationalists, such as the current incumbent, who have traditionally simply restated impersonal apologies. Whether because of familial ties or personal beliefs, Prime Minister Abe seems to once again be following this tradition much to the chagrin of many Asians and friends of Japan. Overcoming the past is never easy particularly in the current context of East Asia. Yet the lessons from the U.S.-Japan experience teach us that by personalizing our own histories we can look towards a brighter future.

For Japanese, August 6, 9, and 15 are solemn days to reflect on how the Great Pacific War went wrong with imperialism and militarism but also the price that was paid. They are days to remember so as to protect against ever going back to those dark days. Japan's wholehearted "embrace of defeat" at the hands of its once bitter enemy the United States has been an integral part of its postwar narrative and global rehabilitation. Prime Minister Abe's historic speech to a joint session of Congress earlier this year personified this reconciliation as he brought together two former enemy soldiers to shake hands as he told their stories and offered Japan's "...eternal condolences to the souls of all American people that were lost during World War Two."

Prime Minister Abe's personalized approach in Washington made me realize that my own journey with Japan has been influenced not only by my own beliefs as an international affairs practitioner but also as an American raised in Japan whose own grandparents fought against my adopted heartland in World War Two.

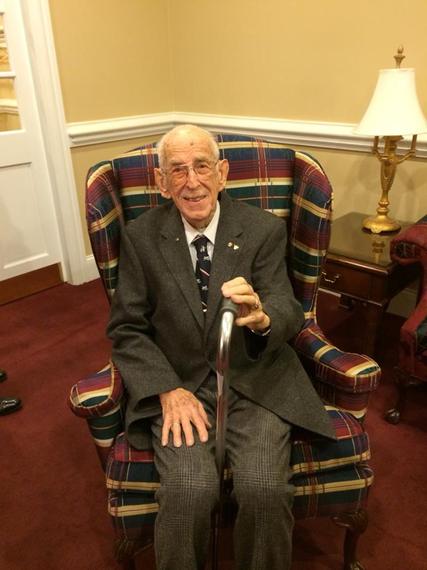

Lewis Graham of Bowling Green, Kentucky, my maternal grandfather, was one of the last remaining B-29 bomber pilots to have flown over and taught other pilots how to bomb the islands of the Pacific. Having lived past 90, the few years Granddaddy Graham served in the United States Air Force during World War Two were among his most consequential, and he was extremely proud of his unit and service. Granddaddy seemed to love Japan every time he came to visit. However, perhaps because I had grown up in Japan from the age of one year old with my missionary parents who lived longer in their adopted heartland than their U.S. homeland or perhaps because he was just quiet, Granddaddy Graham never talked about his wartime experiences. He would only talk about his experience back in the states and the times he had nearly crashed his planes in training exercises while Grandpa Walker, my paternal grandfather, talked often with interest of the samurai swords he confiscated as a former member of the United States Army occupation forces charged with confiscating all weapons from civilians.

Granddaddy Graham was a man of few words. I distinctly remember the fascination of various Japanese church members who asked questions about his wartime service when he came to visit us. He would always smile and politely divert the question to his wife who would inevitably have something to say as the "talker in the family." However around the 70th anniversary of Pearl Harbor I happened to visit him in his nursing home -- one of the last occasions I would ever see him alive -- and for the first time he shared some of his reflections.

Granddaddy talked of flying the B-29 and how powerfully destructive the super fortresses could be. He casually mentioned that he had trained with the Enola-Gay crew, which would later famously drop the world's first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Having never heard this side of his story before, I followed with a series of questions incredulous that my own grandfather could have brought so much devastation to a country and people who I had always loved so deeply. No he had not dropped the bomb himself, but knew and trained with the crew on the same islands in the Pacific. He flew a series of missions that did drop bombs across the Pacific. It was a necessary evil to bring the war to a close, he said. The Japanese were a proud and determined people that would have fought to the last person if America did not drop those bombs.

Tears began to form in Granddaddy Graham's eyes as he saw the look of devastation on my face as I tried to reconcile the horrible irony of his work to "rescue" Japanese from their military leadership during the war and my parent's work with the Japanese today that involved 3/11 Tsunami disaster relief, English language teaching, and spiritual counseling. They were not tears of sorrow, but of memory of an old Japanese church member that I learned had thanked him for his service on his last visit to my Japanese hometown. I had experienced this myself on numerous occasions growing up in Japan, where I as an American would sheepishly try to tiptoe around certain aspect of World War Two's history only to be thanked on behalf of Japan for what America had done for its people. The level to which Granddaddy Graham had reconciled this past Japan that he had bombed into submission with the Japan of the future that he so thoroughly embraced because of his daughter and grandsons' love of it is one of the most powerful and vivid memories I have of him.

Confronting and reconciling such personal historical memories is never easy, but it is necessary to move forward. My own Granddaddy's evolution is instructive at a broader level of what is possible within just a few generations. Despite how different countries remember the past, having a shared future and a personal story makes the journey that much more interesting. Why Granddaddy Graham only remembered or chose to share his own involvement and memories of his past towards the end of his life, have helped me understand my own role as a bridge between the United States and Japan that went in his lifetime from bitter enemies to indispensable partners. Therefore while the historical memories might initially bring pain the personal reconciliation I saw through my Granddaddy's eyes gives me hope for the future in the longer term.