Judith R. Walkowitz is the author of Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London (Yale University Press, $40)

In the twentieth century, London's Soho district became a tourist mecca, where Londoners could indulge in forbidden appetites of sex, food, and drugs, not to mention late-night dancing and drinking. Despite its sleazy exoticism, Soho in the 1930s boasted one local institution that catered to middlebrow suburbia.

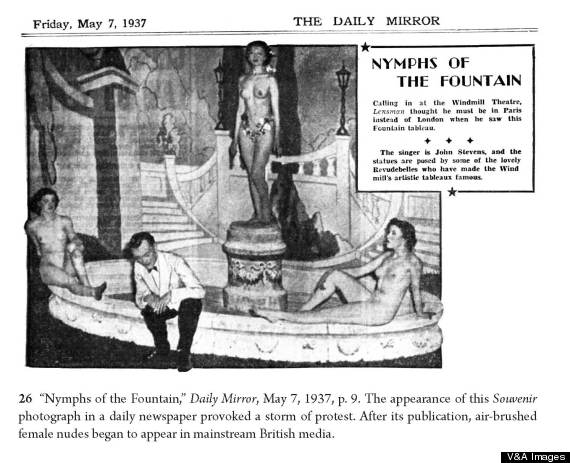

The Windmill Theatre, a tiny variety theatre specializing in "girls and gags" and tasteful nude tableaux, attracted male commuters eager to experience erotic entertainment in a safe, licit, strictly white venue. The Windmill's success hinged on the savvy marketing strategies of its wealthy theatre owner, Mrs. Laura Henderson and her Anglo-Jewish manager, Vivian (V.D.) Van Damm.

To promote the Windmill, V.D. publicized the variety theatre as a philanthropic defense of "all-British" live entertainment, speedy and up-to-date. He also introduced stage nudity, or the "bare idea." Mrs. Henderson used her society connections to persuade the theatre censor, the Lord Chamberlain, to permit the staging of nude tableaux on the grounds that they were artistic renditions of classical statuary or paintings.

By remaining motionless under subdued lighting, the Windmill nude poser was "art." But if she moved, she was "indecent." Posers could not smile, they tended to look off into the distance, and they had to place their front foot forward so nothing would appear in what was referred to as "the fork." Nude tableaux were the main attraction for the stall patrons, who tried to gain a seat in the favored front rows, known as the full sight seats. Included in their ranks were the surreptitious masturbators, the "dirty mackintosh" brigade.

Mrs. Henderson's subsidy kept the Windmill afloat during the depression, but the theatre's wartime prosperity pulled it out of the red. 1939-45 proved to be the Windmill's "vintage years," when it consolidated its legendary status. On Sept. 7, 1940, there were 42 theatres running in London's West End: "then came" the bombs and, to quote one reporter, "only the little Windmill" was still "on its feet." The Windmill immediately put up a banner, "We Never Closed."

The press was quick to exploit the visual attractions of the Windmill at war. Photographers took backstage shots of the Girls that amalgamated home and work, glamour and grit, in service to a "People's War." The Windmill girls epitomized the home front fighters at the center of the urban war zone, putting aside their private lives and collectively demonstrating a public resilience.

These backstage scenes operated at different registers. Bedtime scenes blend two genres of wartime photographs, the shelter scene and the pin up. The cover of the racy periodical, London Life, features Windmill girls asleep in their "civilian dugout." Pressed together in bed, apparently undressed under the covers, hair in rollers and headbands, their faces are carefully "made up."

The nude "four-in-a-bed" photograph evokes the underground pornographic genre of the lesbian brothel scene. Bedtime pictures in the popular press are much cozier and discrete. For example, "Our Daily Life in Air-Raided London" presents three "girls" asleep on the floor, keeping up appearances, but their bodies are decorously separated and fully-clothed. One Windmill girl remains awake. Photographic scenes of the gallant Windmill Girls were exported to the US as propaganda for the Blitz spirit: glamorous testimony that "London can take it," that Londoners had formed a self-sufficient, democratic "civilian army" to resist Hitler.

A new wartime audience of American servicemen consolidated the Windmill's international reputation and allowed the Windmill to make a profit. One American newspaper calculated that over a million G.I.'s saw the shows and contributed over 200,000 dollars to the Windmill's wartime prosperity.

An urban legend circulated around the presence of American servicemen at the Windmill. It involved their breaching of the theatre's intensely British decorum. For three and a half years, G.I's sat in the auditorium, "smoking cigars... and yelling 'Take it off, Take it off'." One showgirl remembered the Americans fondly as "the grandest audiences, much warmer than our English. And they were really very well behaved, after you got used to the shouting."

Another urban legend circulated around a posing girl who came to life amidst detonating bombs in 1944. After a flying bomb hit the top of the nearby Regent Palace Hotel, a posing girl wearing a Spanish hat (and nothing more) slowly moved and thumbed her nose at the bomb. For this "spontaneous gesture," she received a "tremendous ovation." Reflecting on that special occasion, VD added, "I am sure that the Lord Chamberlain would not have objected to this posing figure moving."

The posing girl who moved epitomized the spirit of the Blitz, when wartime propaganda recast everyday ordinariness as an idealized expression of homefront morale. The Windmill staged a form of British popular entertainment that came to the defense of the nation by amalgamating performance genres that were "in some ways Transatlantic, in others Continental." Its erotic entertainments were simultaneously wholesome and prurient, civic-minded and cynically commercial.

While embracing the moral solidarities of interwar middle England, the Windmill came to embody the heroism of the "little people" of London, a testimony to their determination under fire.