Who is worthy of redemption? Do criminals deserve a second chance? What about murderers?

Shaka Senghor explores these questions through his own life experience as documented in his memoir Writing My Wrongs. At 14 years old, Mr. Senghor ran away from home to escape his abusive mother. Being a teenager, he had little survival resources and often went long periods of time without food or adequate shelter. When he was approached by crack dealer offering him work, it was impossible not to be seduced by the quick money and the fast lifestyle. Unfortunately, he underestimated the dangers of the drug trade; among the many consequences that came along with his career choice, the most life altering was undoubtedly when he was shot.

Full of fear and paranoia, Mr. Senghor purchased a gun himself. After 16 months of owning the gun, he shot and killed someone during an altercation over a drug deal. At 19 years old, Mr. Senghor was convicted of second degree murder and sentenced to 17-40 years in prison.

Within his first six weeks of imprisonment, Mr. Senghor writes he "had witnessed everything from rape and robbery to murder." Filled with rage, resentment and fear, Mr. Senghor became vicious, which not only led him to the top of the prison social hierarchy, but also got him assigned to solitary confinement for a total of seven years, four of which were served consecutively. Most people had written him off as a "lost cause."

But fate had other plans for Mr. Senghor. Five years into his sentence, he received a letter from the godmother of the man he had killed. In the letter, she had asked him to tell her what happened the night of the murder. Mr. Senghor was taken aback by the request, but responded to her letter honestly, knowing that he, at the very least, owed her some closure. She responded two weeks later. "She said that she forgave me and encouraged me to seek God's forgiveness," Mr. Senghor recalls, "and I took her words to heart."

Mr. Senghor eventually began his own arduous journey of forgiveness and empathy, much of which occurred through journaling. "Within the lined pages of my notepads," Mr. Senghor writes, "I got in touch with a part of me that didn't feel fear whenever something didn't go my way-a part of me that was capable of feeling compassion for the men around me."

While on this path to emotional wellness and understanding, Mr. Senghor also took the opportunity to educate himself by visiting the prison library every opportunity he got. He started reading literature from great African American writers such as Donald Goines, Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, Assata Shakur, and George Jackson to name a few. "My reading of Black history gave me a sense of pride and dignity that I didn't have prior to coming to prison," Mr. Senghor explains.

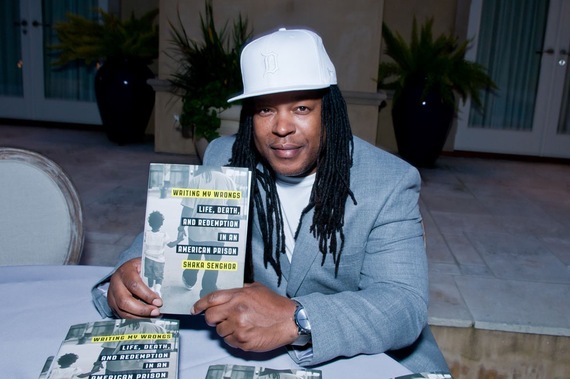

Photo credit: Alain McLaughlin

With the rise of his self-confidence as a Black man along with his own exponential emotional growth, Mr. Senghor was becoming more and more dedicated to being a better person. However, the social expectations in prison would often force him to compromise on his new resolve. As he puts it in his book, "I was growing in my consciousness, but the gravitational pull of prison life was overwhelming."

One of the most intense examples of this conundrum was when his old bunk mate asked Mr. Senghor, who had recently transferred prisons, to do him a favor: "He said that a guy who had molested his son and niece was at the prison I was in, and he wanted me to take care of it." Mr. Senghor continues, "I was conflicted. I had stopped using violence as a way to solve problems. I was tired of the madness of prison and all of the street codes, and all I wanted to do was move on with my life." However, in order to survive in prison, Mr. Senghor was expected to engage in these types of conflicts or risk some form of retaliation; either way, he would be forced into a violent situation.

One has to wonder how anyone is supposed to not only survive in this type of environment, but then successfully reintegrate back into society? This question is particularly important considering that 95% of all state prisoners will be released from prison at some point.

When Mr. Senghor finally received parole, an officer predicted that he would only last 6 months outside of prison. Since his release in 2010, Mr. Senghor has graduated from the M.I.T. Media Lab fellowship, taught at the University of Michigan, and given a thought-provoking TED Talk. Today, Mr. Senghor continues to travel across the country to continue this conversation about prison reform. He also frequently visits prisons to inspire inmates and assure them that, even though the cards are heavily stacked against them, there is hope.

While Mr. Senghor has succeeded against all odds to become a positive force in the world, one has to wonder why we aren't making it easier for prisoners to redeem themselves? As Mr. Senghor writes, "you can't change a person for the better by treating him or her like an animal. The way I see it, you get out of people what you put into them."

This brings us back to the original question: who is worthy of redemption? Is Mr. Senghor? He did, after all, kill someone. During his first parole review, Mr. Senghor talked about his plans after prison, specifically about the book he wanted to publish and the work he wanted to do when we was out. Before he could finish discussing these plans, the parole board officer curtly interrupted, "That's cute that you have books, Mr. [Senghor], but it doesn't take away from the fact that you picked up a gun and decided to use it to kill someone."

Although Mr. Senghor was denied parole after this particular review, he still maintained his resolve; in his eyes, he was worthy of redemption. Two years and two parole reviews later, Mr. Senghor walked into the world as a free man.