Entertainers are driven by two commandments: Be Entertaining, and Be Informative. Unfortunately, it's been a red-letter day whenever someone was actually successful at doing both.

For each instant classic such as Thank You For Smoking or Hotel Rwanda, there have been a dozen moralizing or demoralizing titles that have left their audience caring even less about world affairs than they did before they sat down.

Sometimes these well-intentioned missteps are semi-exploitive; yet another white man runs around in a half-unbuttoned shirt and Banana Republic cargo pants saving Africans from themselves. Maybe he even dies in the end, leaving the audience with a warm feeling in their tummies and the illusion that Someone Is Doing Something.

The other common pitfall is packing an entire college course worth of information into a two-hour script and then proceeding to beat the audience to death with it. This is usually a route taken by bad theater, and smart directors of these shows will insist on there not being an intermission where people can escape into the night.

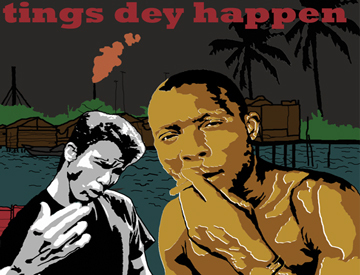

Thankfully, there are artists like Dan Hoyle. Dan is a white guy who went to Nigeria on a Fulbright Scholarship to make a play about oil politics and globalization. His one-man show, Tings Dey Happen, pulls no punches in communicating the devastation visited on Nigerians by oil companies, corrupt politicians, well meaning but clueless Westerners, and their own violent power struggles. It is also an incredible amount of fun.

Playing a range of characters - many of which are Nigerians speaking in heavy pidgin or Nigerian accents - Hoyle runs a 90-minute gamut of emotions that stretch from the poignantly heartbreaking to the hilarious, all while imparting the facts of the situation without condescension. I was able to sit down with him in New York to talk about what he thinks makes the show a success:

JH: What was your original motivation for creating Tings Dey Happen?

DH: I had gone around the world in 2002 on a circumnavigator's grant studying globalization, and when I got back my professor at Northwestern, Mary Zimmerman, gave me this New York Times article on Escravos, which is a village in the show. She said everything you've been studying is in this village. It's this epic place, right next to a Chevron flow station. The land is sinking into the water because there's been so much seismic activity. You look all around at night and it looks like a thousand setting suns, but it's really just the flares from the oil stations.

And the people there are the greatest storytellers in the world. In terms of globalization, there's a corrupt government, big oil company, poor villagers, international news media. It's all the elements you need for a first class, strange, immediate drama. The people there have figured out that the international press is their way to communicate to the outside world, they're mediating it, and we're receiving it through a strange filter. So I said I'll go there and try to show what's happening from the inside.

I applied for the Fulbright grant and got it in 2004, the same day a couple of oil workers were killed near Escravos.

JH: When you began writing, what were the pitfalls you were most concerned with avoiding?

DH: Making sure the audience doesn't get overloaded, that they feel taken care of. It's a challenging show, especially for people who have never been to Africa, it's just this thing that they read about and that celebrities have talked about for the last couple of years. I think Africa is looked upon these days with either a lot of pity or guilt, and I don't think either of those emotions is really useful. I think curiosity is a galvanizing force, because it makes people want to know what's really happening. It's only when you know what's really happening that you can do something that's meaningful or impacting.

JH: What do you think was the most important decision you made when creating the show?

DH: Taking myself out it. That was the key to finding the intensity of Nigeria in theatrical form: not having the comfort of Dan always being there.

Then I created The Narrator, Silvanis. He's the cultural translator that comes in just when the audience is going, "Oh my God, what's happening?" All of a sudden we're 20 minutes into the show and we've been introduced to this sniper who's talking about killing people to earn money to go to college, and the show is fast moving. From my perspective, I want it to it to be real, and intense, and serious. He's coming from the perspective of, "It's a play! Enjoy yourself! Don't run away! Don't be scared or overwhelmed by Africa. You can find your way in. Look at this guy: he's a person, he's not a character, he's not standing in for a thousand people that are like him, he's an individual and he's different."

The show kind of starts out as this hardcore political show, and then it becomes about these people. Which I think is the truth about all of these situations. All politics are local politics.

JH: The role of the narrator reminds me of the comedic relief Shakespeare used in Macbeth when the audience couldn't take much more. Was there an original impulse to use comedy as a way to tell this story, or was that something you developed during your time in Nigeria?

DH: Both! Nigerians are really funny. They have a hilarious sense of humor, they're really good storytellers. The truth about Nigeria is that even though really devastating things are happening, your average day in Nigeria is a lot of fun, because that's how they cope. "No ting dey happen." Nothing's ever happening, unless something REALLY bad happens.

It's like a party where a dog ate the cake and the lights are out, and there's a hole in the floor, but people are still partying. That's kind of like Nigeria. People aren't walking around every day telling these really hardcore stories. Most of the time, they're having a good time. If you can make people laugh, you can tell them anything. You need comedy; otherwise people aren't going to come. It's one thing in a medium like film in which you have all this visual spectacle, but in a solo show you're asking people to look at one person for ninety minutes, so you have to make sure they're having a good time. And then as they're having a good time, hook them into the story.

JH: When you took yourself out of the show, what's left is you playing characters who are mostly black Africans speaking in pidgin or heavy Nigerian accents. That's a scary artistic choice for a white guy, even by New York standards.

DH: It's funny, you know. Honestly, once I got to Nigeria, I knew these people were going to be characters. I know them, I hung out with them, and I tried to learn and understand how they think the same as I did with the white guys I met in Port Hartford. The process was the same trying to get inside that circle: the journalism of hanging out.

So funnily for me it never felt risky. I forget that. Because every night when I come on stage, people are going, "is this okay?" And then they somehow get that it is. The response from Nigerians has been overwhelmingly positive. I hope those kind of choices in the future are considered less risky.

The thing that baffles me sometimes, Wes Anderson's new movie (The Darjeeling Limited) - and I have nothing against Wes Anderson, I think he's great - but it uses India as a set piece. You don't learn anything about India. Everyone appears as these completely foreign, brightly dressed set pieces for three white guys. And no one would even begin to think that's weird.

But for me, who took to trouble to get to know and live in Nigeria for ten months, hang out in these hinterlands - creeks and bushes way out there where conditions are pretty rough - and get to know how people live and think, I thought the best way to show that to audiences is to become them. And that is perceived as so much more risky.

I think if you do it wrong, it's awkward. But I never had any fear of doing it wrong. The only audience I was scared of was the white people. I knew Nigerians would appreciate it. The only comments we've had have been from a very few amount of white people, really scattered voices in the dark, but overwhelmingly it's been well received and I'm proud of that.

I hope that space continues to be opened in that way, otherwise it impinges on the possibilities of figuring out who we are. Because we are different. We're all humans, we have the same emotions, but people in Nigeria and San Francisco think differently, their realities are different, and that's okay. And if we try to understand each other, it will be okay.

What I think tends to happen is people get so worried about offending each other that we don't learn about each other, and so what remains is this reverent ignorance.

JH: I was really happy to see a Richard Pryor impersonation in your show. How much of a background in Pryor did you bring to it?

DH: The reason that scene came up is because I had Malaria, and I read a bunch of Graeme Greene novels and watched this Pryor DVD over and over again. Richard Pryor became this voice inside my head saying, "You're still here? You're sick! Go the fuck home!" And Graeme Green was the voice saying, "No, you have to stick it out and get the story!" These two heroes of mine were battling inside my head as I was having these hallucinatory dreams. Pryor died while I was in Nigeria. Robin Williams came to see the show in San Francisco, and he talked about Richard and how he thought he would have liked it. For anyone whose ever performed, [Pryor] is brilliant and broke boundaries in a liberating way.

JH: Kurt Vonnegut said once that artists didn't stop the Vietnam war, that the best they did was poison the minds of future generations against fighting for illegitimate reasons. What do you hope the impact of your work will be?

DH: I try to make art that teaches or encourages people how to think, which is critically not what to think. People are used to Agitprop Theater that says, "here's the monster, let us all shake our fist at the monster."

Those people come out sometimes saying, "Now what exactly am I supposed to do?" There's no petition to sign, no line to picket on. The central question of the show is western intervention in the rest of the world. That runs the spectrum from Peace Corp. volunteers to tanks rolling into Baghdad. What is not valued these days is what the people living there think about what is happening.

Too often people from both the right and the left impose their world view on these situations. They read the newspaper and go, "ah, exactly. It's just as I've always said." There are two kinds of people: those who read to have their beliefs confirmed, and those who read to have their beliefs challenged. I'm trying to encourage the latter and push for the idea that we have to know what's happening in these places, or any intervention - be it benevolent or military - is doomed to failure. History bears that out but we keep forgetting it. I hope to encourage people to be curious; debate things, and be wrong, and be okay with that.

JH: The last line of your show comes from an Nigerian official yelling at you to "think like an African." When did that dawn on you as the essential ingredient?

DH: My process is always to go bush, go local. I tried to become a Nigerian man for the purpose of understanding what was happening. It started out from a position of research. Part of it is seeing a reality that's so raw and real, and feeling like I have to portray that or else I've failed. That has to be the starting point, the Truth of What Is Happening, and to let that scramble people's minds. I owe that to the people I hung out with and the research.

Reading how things were reported so that Western audiences could understand them frustrated me. Being able to portray it on stage without that filter, having the privilege of attempting to have the audience see things through the eyes of a Nigerian for ninety minutes, that became my responsibility.

JH: What would your advice be to an artist who wanted to create a work like yours, whether or Iraq or Darfur or any other highly political subject?

DH: Be prepared to have your political philosophy shattered. Be prepared to be proved wrong, and have the story you thought you were going to tell be inadequate. Even though a lot of people want the story to be told a certain way, in the end, you have to answer to the truth.

- Tings Dey Happen is currently in its second extended run at The Culture Project in New York until December 22nd.

One might visit Dan Hoyle at http://www.danhoyle.net/