You just enjoy it. Every moment of Richard Loncraine's new film My One and Only is joie for the eyes and ears. The story? Nothing too complicated: a woman storms off on her unfaithful rich husband, gathers her two sons, and embarks on a road trip in a shiny Cadillac El Dorado, en route to snag a new rich husband and father for her kids. Based on actor George Hamilton's true childhood experience, it is not only the witty classic Hollywood script -- written masterfully by veteran Charlie Peters -- that makes the film a winner. Loncraine, like the over-the-top directors of old, knows how to make each scene a tour-de-force of acting, style, and pleasure.

We have Americana shots of 1950s pink Cadillacs on downtown Main Street, shimmering under a wide blue sky, the beauty of the Arizona desert stretching into the horizon, and more than a few kitsch shots of amber-hued hotel rooms with floral print curtains. But even more than the set (and the costumes! the mother's exquisite summer-white suits, decollete and sleek; the boys' polished schoolboy shoes), there is the acting. The mother (Renée Zellweger) is splendid, and so is her older son Robbie, played by Canadian Marc Rendall, a droll prince of camp whom we first see on the sidewalk in New York smudging his make-up from his role as Lady MacBeth. Ostensibly gay -- and delightfully effeminate -- the boldly red-haired boy has the discreet role of straight-man in this film, the one who peppers the film with sleight-of-tongue expressions such as "paler than a nun's behind" and offers such wry deadpan comments such as: "Mom is getting a job? Do you mean, the kind of job that requires working?" And commenting on his Mother's new beau, a repressed military man with a violent flair: "Why does he still wear that uniform? Doesn't he know that the war is over?"

The audience at Berlin -- where this film premiered last week -- laughed out loud, and many left with great smiles on their face. "What a relief," said one journalist. "After seven days of grim films, we needed this!" Another said it was the best she had seen: "At least I am leaving Berlin on a happy note."

I met the director, Richard Loncraine, in the elegant lounge of the Potsdamer Platz Sony Complex (far from 1950's decor, this was state-of-the-art post-modernity), and he was as jolly as his film. A beaming man, dressed totally in grey (grey t-shirt, grey pants, grey hair), with happy crows-feet wrinkles, he immediately insisted -- to us five journalists -- that he did not take this directing business too seriously. "I'm not a dedicated film director; I like so many things; I like cycling, in fact, I just cycled in Africa and China. I love technology. I love cooking. There are so many things I want to do. I was once an inventor, and a sculptor. You know those five still balls that demonstrate Newton's third law of motion, that you see on office desks sometimes? I invented that! I used to sell toys and make them up."

He continued enthusiastically with his tribute to invention. "Film-making is just wonderful, but there are so many other things out there. I am sixty two and I still have so many things to learn about. I have a lovely home in France, and I was trained as an engineer and sculptor, and my next project is to go to invent things in France."

As for invention on the set, Loncraine explained that above all he chooses a great crew -- a stellar costume designer, set-designer, cinematographer. Accepting the compliment that his film was a visually stunning, he avowed that he himself doesn't have a fixed idea of the look of the film before he begins to shoot. He waits to collaborate.

"But I had an idea early on. I love the postcards of the period. The towns. And maps. Robbie is embroidering a map on a bowling shirt -- this was my idea. I took this idea of a road journey, and then discussed it with Brian [Morris], the production designer. Brian and I lived together in a trailer for ten weeks, on prep. I would cook, and each day we would chat about the film.

What about the colors? The palette of each shot is quite distinctive.

"For one thing, I don't use the color green. It is a hungry color, it absorbs more light than others. I don't like green with other colors. Already, when you shoot, you have red. Faces are red. If you have red, blue and green, that's too colorful a palate."

He continued, brainstorming as we sat. "Now if I were shooting here--" he looked around the lounge. "I would stick to the amber tones. I would keep that red purse on the bar stool..." (I personally was happy about that, as it happened to be mine). "But..." he paused, glancing directly at me. "I would take off your pink shirt."

As for how he achieved the joie-de-vivre performances in his film (rare is a film, where you just eat up the performances), Loncraine responded: "I feel the joie with my cast, so they express the joie.",

I took Loncraine aside after this jolly encounter, and asked if he himself was really as cheerful as his own film. His character Anne Devereux (the mother) always says 'Things turn out for the best' (a line her son Robby claims she would even repeat on the electric chair, with steam coming out her ears), and indeed, even though there is death and disappointment in the film, it always does turn out for the best.

Was this his personal philosophy?"

"Oh I don't believe that at all," said Loncraine calmly, with his first serious look. "I am an atheist. I don't believe in anything. I don't think everything always turns out for the best."

So why such a happy film?

"I wanted to make a film that made me laugh as much as the script did when I read it. There is so much sadness in this world, I'd rather make people laugh for two hours if I can. Laughter is a leveler of pain. If you can laugh, you can't be violent, you can't be afraid."

He added with a quizzical smile: "My film also celebrates the fact that human beings look after each other."

Indeed, by journey's end, the mother does not need a rich husband after all.

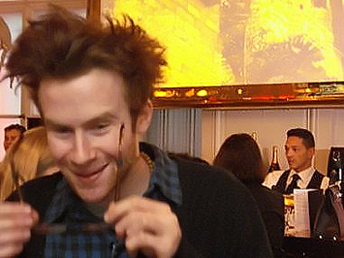

Marc Rendall plays "Robbie"