It is always a heady experience to return to the Thessaloniki Documentary Film festival in Greece, held each year in March. In a matter of a few days, one gets an intense update on the major issues of the planet, from "google babies" to ecological disaster. And it's exciting. Where else can you experience a morning with cannibals in the Soviet Union (Cannibal Island), an afternoon with Polynesians escaping a flood (There Once Was an Island) and an evening with William Burroughs (William Burroughs: A Man Within)? Or be inside a Guantanamo interrogation cell (You Don't Like the Truth) and see a boy be offered Subway sandwiches in exchange for turning in his father.

The treat of this year's festival was the spotlight on Czech documentary director Helena Trestikova. Each of Trestikova's documentaries is a tragedy-in-the-making, offering a scrutinizing gaze on one individual and following the trajectory of his or her life in a time-lapse profile, much in the style of the renowned Seven Up series. We become intimate voyeurs, watching as a cheerful young person becomes, in the course of the years, hardened, bitter, or destroyed (or not). For example, in Katka, the director features a pretty girl who, early on (bad family), becomes a heroin addict, but who later--about to realize her dream to give birth--must face the "choice" of quitting drugs so as to be a good mother. The suspense is painful: it becomes clear that early drug use predisposes the heroine, more than even an Orphic-cursed Oedipus, to an impossible lack of decision-making capacity.

The intrigue in Trestikova's films lies in the ambiguity between where one chooses one's destiny and where fate is too strong.

In the award-winning Marcela, the director follows a working class woman for twenty-six years. We watch as Marcela tries to manage her life through the ups and downs of young marriage, motherhood, divorce and bereavement. Trestikova's achievement is to provoke questions: will Marcela's fate as a single mother in a subsidized apartment, working in the post office, constrain her possibilities for a fulfilling life? Will she overcome the tragedy of her murdered daughter? The film is powerful as a meditation on "character". From the beginning, Marcela's passive uninspired outlook seems to predispose her to a less than stellar life: her most enthusiastic musings (repeated throughout the film) are for a "larger" apartment. One is not surprised how small her world becomes. Yet, the director also sprinkles the film with glimpses of simple happiness, such as when the heroine croons to country western music in a local bar, or wanders through town with her sweet mentally challenged son.

In contrast to Marcela, we have the splendid Holocaust (and Stalin) survivor, Zdenka Fantlova, in Hitler, Stalin and I.. The octogenarian sparkles with beauty and light in her eyes, as she tells us her life story, from losing all her family in Auschwicz to losing her beloved husband to execution by a Stalinist anti-Semitic plot. Zdenka's voice wavers with joy as she explains how one night she stepped out of her bunk in Auschwicz and looked up at the stars and heard the "wires" of the concentration camp "singing' and felt the splendor of infinity--and had the presence of mind to sadly reflect that she was, in this splendor, living like a worm. She recalls her miraculous survival from the camp (because a girl fainted, and she took her place on a train), and how overjoyed she was to come back to her native Prague, feeling ecstasy as she sees a "familiar puddle" in the road. Her eyes water in love--the only time she shows sadness-- as she recalls her husband's last words to her through the prison bars, before he was hung. "You are beautiful," he said.

The husband was right. Watching Zdenka, with her silvery blonde hair, her musical twinkle, is exquisite. And she herself an inspiration. "You can't just lie in bed and say why such a woeful life," she states. "You've to get up and say I've done nothing to deserve this." The film begins with her sharp statement that the good thing to remember about "evil" is that someone always survives. It ends with her chortle: "Stalin is gone, Hitler is gone, but--", she laughs like a child--"I am still here."

The audience clapped in thunderous applause.

Among the new releases in the festival, the best I saw was Amir Bar Lev's The Tillman Story. Framed as an exciting detective story, the film traces what really happened to former quarterback Pat Tillman, killed in Iraq and honored as a war hero by the US government for publicity purposes. We become fascinated with the Tillman family, as they take into their own hands the pursuit of truth and justice, amazingly determined to get to the end of this (an originality manifested as well in their early parenting techniques: no television and freedom to swear!). The family pursues the case all the way to Washington DC, where the Tillman story is given a hearing, in front of four ridiculously sheepish generals.

................................................................

Good Documentaries Versus Bad Documentaries

A side-bar event at the festival is the "Docsinthessaloniki Pitching Forum", a workshop, hosted by the Dutch company EDN (European Documentary Network), that offers novice directors the opportunity to work on their scripts with seasoned mentors, as well as to trouble-shoot their pitches before seeking funding.

I asked one young Norwegian director participating in the workshop what she had learned in the week program.

"I learned that the top criterion for a good documentary is character," she told me. "The mentors told us we must have strong, developed characters in our scripts."

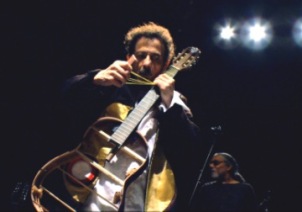

As a point of fact: the most compelling films at the Thessaloniki festival this year all featured fascinating individuals, from Pat Tillman (and family) in The Tillman Story to Tom Ze, the Brazilian singer featured in Igor Iglesius Gonzalez' Tom Ze Liberated Astronaut. The ever-ebullient Tom Ze bursts with creativity and zest as he leads a workshop for young musicians in Rio---using a saw, for example, to make sound. Forgotten for many years (overshadowed by Brazilian stars Gaetano Veloso and Joao Gilberto), the man had a whimsical determination : "I never complained. I just respected the rules of the market". Fate rewarded his perseverance: eventually he was discovered and made famous by Talking Heads David Byrne.

Similarly, Judy Lieff's Deaf Jam, about the phenomenon of the deaf getting into the poetry-jamming movement, is a riveting documentary simply because the deaf Israeli teenager at the center of the film, Aneta Brodski, is so charmingly expressive, especially when she pantomines the sperm and egg dance that led to her birth.: "And that is me!"

In "If A Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation," we have another determined young person, one who gets involved with an environmental terrorism organization, burning down tree logging enterprises, until turned in by a traitor within the organization. Following the subject around in his spiffy kitchen, and meeting his fiance and sister, we become fascinated with the young man's motivations--and his commitment.

But it is Lina Mannheimer's bizarre 14 minute film, The Contract that takes the cake for unusual characters. Strangely uninformative (we never quite know who these people are), it is about a younger woman's decision to devote, by oath, her life to serving an older aristocratic woman, in this case, the widow of author Robbe-Grillet. We follow the two lovers (?) in an elegant French estate, and through its gardens, as the younger woman (who we know very little about) excitedly avows that her joy in life is not her children, the family left behind, but her serving of "Catherine" (who we know even less about). The film juxtaposes shots of these servile/dominant women with sensuous tableaux of 17th century ladies in sado-masochistic poses in a drawing room, the director explaining to me post-screening that she made this film because she thinks domination and subordination is an issue in every relationship.

Director Lina Mannheimer

But there is a second criterion---I was told--for a successful documentary. The film director must know what his or her film is about "We were constantly grilled on this in the EDN workshop,," the young Norwegian director told me. "We would say what we thought our films were about, and they would keep probing; go deeper! What is it really about?"

More than a few of the directors showing films at this year's festival could have profited from such advice. For example, Billy the Kid was a wonderful movie about a strange alienated 14 year old boy: the typical high school outsider who prefers "living in his own head", as he says, imagining himself a superhero. As Devon Bancroft, Nation intern in New York City, who saw the film with me, noted: "The director was smart enough to realize she had found a truly interesting character, and for the most part she leans back and allows Billy to shape the movie himself."

Yet at some points of the movie, the director seems to (mis)lead the audience, with eerie close-ups, to think Billy is a potential serial-killer, especially as we see his queer way of speaking to girls, his eyes shifting creepily in his head, a choice that is not only unfair to the subject, but also not what I believe the director really wanted her film to be about. Case in point is her choice of Billy's last words: "I used to think my imagination was a scary place. Now I realize that the whole world is a scary place." The director could have pushed her film further in this direction, to probe the issue of imagination and alienation.

"A Designer Baby' also could use more focus. It, does an informative job introducing us to the invitro world: i.e. parents who select their children's sex and eye color, single French women who use a Danish sperm bank to choose racially appealing sperm donors (illegal in France) , unscrupulous doctors involved in the process. However, since most of what the film discusses is common knowledge (except here we have a chance to see the masturbation rooms and sperm tanks), it would have been better to choose one particular angle. The most original section of the film is when the director interviews a now adult sperm-bank-produced human, a man so obsessed with his lack of "family", that he went on the web and google-found his six half-brothers and sisters, all sperm bank creations. A film just on this man---and the issue of what it feels like to be the first generation of donor-kids, would have been interesting--and more focused.

I also had a brief email chat with Tom Jarmusch (brother of Jim Jarmusch) whose film Sometimes City premiered at the Thessaloniki film festival. For me, his random interviews with various down-and-out characters in Cleveland, on sidewalks and in living rooms, while charmingly syncopated (in the Jarmusch family style), with intermittent jazz music and grainy shaky filming, did not result in a clear "what is this about"--although Tom insisted that for him, it was exactly the Cleveland he wished to express, "meant to be an imperfect portrait."

Two French celebrity photographers whom I befriended at a lunch excitedly told me that the good thing about documentaries is that even when they are bad, they are still interesting to watch---because it's real. Of course, it's much better when they are good, but even the abysmal film this couple and I saw together, A Man Came and Took Her, about a Polish villager's murdered child and pursuit of the killer through fortune tellers, turned out to be fascinating, as a chance to be in a snowy Polish village and eavesdrop on villagers struggling with ethical questions.

No matter what, the documentary film always offers a new slant--and a chance to travel.

"I want to make the world a smaller place," festival founder Dmitri Eipedes opined. "And documentary film can do that."