It was the most controversial -- and hated -- film at Cannes this year.

The audience at the premiere press screening of Lars Von Trier's Antichrist booed -- with loud hisses (and a few hoots of laughter). "How dare he show us this!" exclaimed more than a few. The film is about a marital relation gone awry, following the death of a child --a rapport marked by anxiety, cruelty and an endless dynamic of power manipulation. The climax is a clitorectomy, executed with a pair of scissors, right in the audience's face.

Yet, I liked it. Von Trier is known for films simmering with mental torment. Antichrist just happens to be his most autobiographical -- his most raw. It is as if someone had excised his mind and played his nightmare right there, for the public, and what one sees is -- indeed -- quite ugly. As perhaps it would be for many of us.

Von Trier noted at the press conference that he had made this film following a "deep depression". As for what it is about -- a question posed by an irate British journalist ("I demand that you justify your film now!") -- he stumbled, raised his hands helplessly, and stumbled again.

I intuited what it was about. I had interviewed Von Trier four years before and in the middle of our conversation, on the terrace facing the bright Mediterranean sea, he had spurted out, with some humorous self-deprecation and no small degree of anger, that his mother would not let him dye his hair when he was a kid. The hurt was palpable. And evidently still alive...

Indeed, the first shot of Von Trier's new movie is a remarkable scene (everyone loves it) in slow motion to Handel's music of two parents making love, while a little boy (in an allusion to Freud's Wolfman) quietly watches and then climbs out a window to his death. One cannot help but hate the mother who orgasms as her son splatters in the snow. It is this mother who becomes the centerpiece of the film as she suffers anxiety attacks for her "guilt".

"Are you the little boy whose mother lets him die?" I asked Lars Von Trier, pointblank, once more facing him before the Mediterranean sea in Antibes.

"Yes, that is it," Von Trier -- spiffy in his white undershirt -- readily admitted. "My mother didn't give me a childhood. She was magical to me of course, but she did not take care of me. If I were to say, will I die tonight, she would say "Perhaps." Her ambition to tell the truth was more important than protecting me. If my children ask the same question, I say no, you will not die. There is a lot of guilt in my female character."

He added: "I guess I wish that my mother would feel guilty."

Yet the psyche is more complex than that. Charlotte Gainsbourg, who plays the mother (in a genius performance), met me later and told me that she is Lars Von Trier in the film. "The anxiety attacks the mother has after the death of her child: this is Lars." Gainsbourg defended the film as a veritable journey into madness -- "something I don't want to connect with," she added.

A calm healthy young woman, dressed casually in faded black denim, with a single diamond pendant hanging on her gray t-shirt and no-make-up on her boyishly pretty face, Gainsbourg -- legs hooked up akimbo on her wicker chair -- seemed an unlikely actor to play such a tormented malevolent soul.

"I don't know why he picked me," said Gainsbourg. "It is obscure."

As for Von Trier's reputation as a cruel director with a misogynist streak -- who tortured Nicole Kidman and Bjork before her -- Gainsbourg smiled and shrugged. "I find Von Trier intimidating," she said with her appealing soft-spoken British accent. "He has a quietness and a shakiness that I respect. No he is not at all brutal with his actors, as rumors portray. It is tense to make a film with him though: we knew he could have an anxiety attack and leave the set at any moment. I needed him, yet I could not protect or help him in any way."

A moment later she confessed there was one hard moment on the set. "The strangulation scene was the worse. Lars made me watch strangulation videos on the internet."

"Real strangulation scenes? Snuff films?"

"Oh, oh..." she paused flustered. "I don't know. He wanted the shot to go on for ever. He would take me to the limit, stopping only if I needed to breathe. I was willing to go very far. I was willing to be out of breath."

Yet, despite being strangled, true to misogynist logic, Gainsbourg's character is the evil one, not her husband named "He". She is the archetypal Eve (indeed the movie takes place in "Eden") who writhes sexually like a snake -- and even makes love to a bloody penis.

Indeed, she may or may not -- the movie suggests -- be a witch.

"Are you a witch?" I asked directly.

"No, I don't think so," said Gainsbourg. "I don't know who I am. I am just 'she'. She comes out of nowhere. I would prefer to think she invents the idea of a witch because of her own feeling of guilt. But I do not know."

I asked Von Trier the same question. "Is she a witch?"

"Like all women." Von Trier retorted.

"Are you sure you want me to publish that?" I said, giving him a second chance.

"Go ahead!"

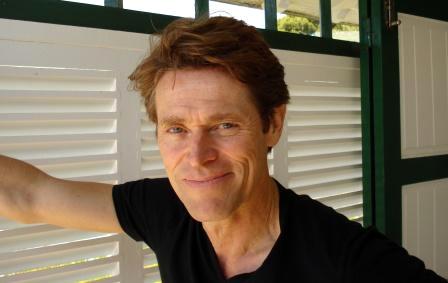

Willem Defoe had the most evenhanded angle on the film. "No, she is not a witch. She is just positioned as the villain. The movie is about a couple that starts off in one and place and then morphs and twists until the end."

The most intriguing question is what happens at the end. Not only at the end of the film (there is a puzzling last shot of naked women rising from a bluish forest), but at the end of going through such a torment -- for both Von Trier and the audience.

"Is there really no hope to heal from one's pains?" I asked Von Trier -- knowing this was a leading question. The film takes a wicked potshot at therapy: Dafoe's character is a cognitive therapist whose blithe idea that "thinking patterns" are all that matter and that "Freud is dead" is proven dead wrong by the revenge of the unconscious in the film.

And the audience certainly did not feel any "release" or catharsis from Von Trier's nightmare journey into madness -- hence the boos.

Von Trier was quick to admit that his own years of "cognitive thinking" therapy were nearly futile: "Cognitive therapy has helped me but it is not a miracle cure. But it is very important to trick yourself and find out only later it doesn't work."

What about God? Has this director -- who forayed into the miraculous strength of belief in his Breaking the Waves -- any truck with religion?

No.

"I am disappointed by religion. I am not a believer. Every time you think about religion, it becomes more obvious that it is an invention of men. I am quite sure there is something beyond but these books -- like the Bible, and religions -- like Scientology -- don't seem very divine to me."

For Von Trier, the only solution is drugs.

"I had some good years on Xantax. People can be in such misery and pills can help."

But -- in a striking moment -- Von Trier did reveal there is something beyond drugs to take one out of the no-exit trap of the psyche. When discussing how he got the idea of a talking fox, he noted that he had had a shamanistic experience where he met a red fox. Then he met another two white foxes who said to him: "Do not trust the first fox you meet."

"He is a shaman!!!" a fellow journalist with a scruffy beard whispered to me excitedly. "What a scoop!!! My parents are shamans, and he is speaking like a shaman. Did you notice how he has done twenty trips? How he mentioned his 'animal' is the otter!"

"What does that mean?"

"Every shaman has his leading animal, who comes to him in a vision. For Von Trier, it is the Otter!"

The revelation about the Otter is more than an occult tidbit. Shamanism -- as described by anthropologists such as Levi-Strauss -- is a voyage into symbols: the patient is led by the story-telling shaman to use her imagination to reconstruct reality on a symbolic plane: to re-write a malady as a narrative -- as a struggle between gods and demons (or witches) -- and in-so-doing position herself as a vanquisher of evil. The new shamanistic story -- Levi Strauss suggests -- has the actual power to heal. Like psychoanalysis -- which is itself a mythological narrative based in symbols (the Oedipal strife being the archetypal symbol par excellence; the psychoanalyst being a sort of shaman) -- the shamanistic voyage works, incredibly enough, because the imagination is more powerful than the "facts": mind over matter.

The imagination is where hope lies.

The upshot: "Antichrist" -- this imaginative symbolic universe of evil -- is, in effect, a shamanistic tale: from its stunning symbolic forest scenes to its strange claustrophobic fairytale hut. In that case, both characters -- female and male -- are Lars himself, his animus and anima battling against each other for resolution.

Following the same line of thought a fellow journalist tried to convince Von Trier that perhaps art therapy (i.e. making a film) can heal the soul more than drugs.

Von Trier conceded that filmmaking was a near-religious experience: "especially when the sounds and images work together." He repeated that this particular film was a breakthrough experience for him.

"I was not afraid to make a film in bad taste," he added. "The images in the scenes come back to some films I made very young, which were never made public. I am not afraid because I had a mental breakdown, and since then I have had a freer access to some things in my mind."

"I think whatever you can imagine, you can show. I don't think there should be any limitations."

Interestingly, more than a few critics -- including, it is said, Isabelle Huppert, director of the jury and Frederic Boyer, former director of the Cannes Directors Fortnight division -- considered Von Trier's film the best in the festival. "Cinematographically, it is a masterpiece," opined Boyer, who is hands-down one of the most erudite cinephiles in France -- a veritable encyclopedia of film shots -- not only running Paris' most prestigious video-club, "Videosphere", but used to watching l000 films per year to select entries for the Fortnight. He enthusiastically waved his hands: "This and Arnold's film were the jewels this year."

Critic Xan Brooks of The Guardian said what I agree with: while other films at Cannes, such as Audiard's thrilling crime story or Loach's fluffy fun, were fine enough, "why, then, is it Antichrist that keeps me awake last night, whirling like a dervish in the darkness of the room?"

As it turned out, many journalists -- speaking undercover, as if about a taboo -- shared positive responses, coming out of the woodwork like ants scurrying from the light. "This is my favorite film," whispered one as he rushed alongside me to a press screening. "I too suffered a depression last year so I get what he's doing. I think though if one has not had a depression -- or any similar experience of self-reflection -- this film will just wash over you."

Still the question remains -- open to readers here: what does a dark universe get you? Does art have to have "transcendence" -- a glimmer of a way out -- to be "art"? Or as critic Alex Billington frames it: "Antichrist is fucked up. In a good way? Or in a bad way? Even I don't know the answer to that question (or maybe that's something you'll decide for yourself)..."

In other words, is Von Trier's fairytale re-creation of the psyche -- which ends with faceless witches rising in a forest -- good for anyone but himself?

And was it even good for him?. At the end of the shoot, Von Trier re-descended into a dark depression.

What is more, the extreme negative reception the film has received -- this veritable witchhunt -- may work against the shaman's medicine. The shamanistic voyage depends on a social contract, says Levi Strauss. It requires reciprocal belief in the new "story": a collective acceptance of its symbols. You can't laugh at a talking fox.

"Of course I am sensitive to the negative reaction of the press," Von Trier admitted soberly -- more intimate with us sitting round him at a table before the sea, than he had been at the press room shouting out he is "the greatest" before the TV cameras. "Of course I am. It's not pleasant when people don't like what you do. You come to your mother with a little drawing, and she says it's wonderful, so you know she loves you."