Editor's Note: This post is part of a series produced by HuffPost's Girls In STEM Mentorship Program. Join the community as we discuss issues affecting women in science, technology, engineering and math.

They led me through the narrow cell block towards that suffocatingly small and dreary room they called the death chamber. It was frightening for someone who had never been inside a prison. I stared at the orange table, at the unoccupied restraints, the very ones meant to pin the convict down for the execution. I was out of my element and my mind raced with horrific images that I felt would be forever etched in my brain.

I jolted myself out of my daze then. I pulled myself together. I had to because I was on Idaho's death row and I had an assignment. As a reporter for a local CBS affiliate, I began my four-part series by taking viewers inside the grimy tiled walls of the death chamber. It was eye-opening for me, the girl who had never come face-to-face with a convicted jaywalker, let alone a felon sentenced to death. But as the day wore on, I eased into my role and abandoned the hesitation that, earlier, had rendered me an emotional robot.

I walked away learning how to adjust to situations outside my comfort zone, a skill that would later prove useful. But that wasn't my only challenge that day in Boise.

I thought my muscles were simply sore at first. But when the camera went off and the adrenaline slowed, the real pain set in. From my head to my toes, I hurt. My joints swelled, my feet ached. Weeks earlier, I had similar symptoms that I dismissed as the flu, but it felt different this time. I felt more sick, more tired. Days later, I nearly collapsed at work, unable to catch my breath because my lungs hurt so badly. The doctor said it was pleurisy, an inflammation of the lining around the lungs. Soon, my fingers became so swollen that I could barely bend them to wash my hair. It didn't matter because I was losing my hair anyway. There was a skin rash and blisters, on my nose and my cheeks. And fatigue. Crushing fatigue. The kind of fatigue that could keep me sleeping for 15 hours and still needing 15 more.

My symptoms were eventually diagnosed as Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, an autoimmune disease in which the body's immune system attacks itself. My search online yielded a website that charted survival in vague terms, claiming 90 percent of lupus patients lived five years post-diagnosis while 75 percent made it to 10 years and only 65 percent made it 15 years. For someone in her early 20s, those odds weren't reassuring. I knew as a journalist that information was power and never in my life had I felt so incredibly powerless. So, I set out on a mission to learn as much about lupus as I could. I never dreamed that journey would eventually lead me to medical school.

I credit my doctors who inspired me. They counseled me, educated me, and when I came in asking question after question, as any journalist would, they praised my curiosity and encouraged me to sideline my love for journalism for a greater purpose. I had my doubts; science had never been my strong suit, so I tabled the fantasy and concentrated on my career. A few years later, I covered the political beat at a midwest affiliate when my news director offered me a promotion to anchor. It came with perks, as well as a multi-year contract. The idea of going back to school was still scary, but it nagged at me. If I signed the contract, I would be locked in for years. I had to make a choice, so I turned down the job, hung up my microphone, and packed my bags, headed to my home state to re-establish residency and return to college.

It took two years in a post-baccalaureate program that included 62 credits in science and math before I could sit for the Medical College Admissions Test and apply to medical school. I was fortunate to get accepted to a school in Missouri, but just before moving halfway across the country, I had a particularly bad lupus flare and in the process of treating it, I was diagnosed with Hashimoto's Thyroiditis, yet another autoimmune disease. The pain was back, along with weight gain, complexion problems, hair loss, and fatigue. Medical school was emotionally and physically demanding and I could barely stay awake through morning lectures. I couldn't keep up. I couldn't concentrate. I used to be live on the air every night without missing a beat, and yet, there were days in that first semester when I couldn't even find the words to express myself. Old insecurities resurfaced and my dream of becoming a doctor spiraled into a nightmare as I was on the verge of failing out of medical school. My confidence destroyed, I almost left, too exhausted to put up a fight. But thanks to my support system, I forged on and after pleading my case, I was given a medical leave of absence.

I returned the next fall, filled with self-doubt and twice as nervous as I had been the first time. After all, I had already failed at this once. What made me think I could do any better the second time around? But I did do better, thanks in part to caring faculty, staff, and administrators who cheered me on. This June, I began my fourth and final year of school. It hasn't been easy, battling these obstacles while pushing through a rigorous curriculum, but with each step forward, I have gained confidence that I can complete this journey. With each obstacle, I have gained even more empathy for those who face adversity. Each time I am confronted with a medical or academic problem, I think about how scared I was about the future when I received my diagnosis and I remember that there are others out there, just as lost and frightened. I think about them and somehow summon the determination to get through my training with one goal in mind -- I hope that I can help them as much as my doctors helped me. I also hope to show that anybody can leave their comfort zone even in the midst of a disease to pursue a goal larger than they imagined.

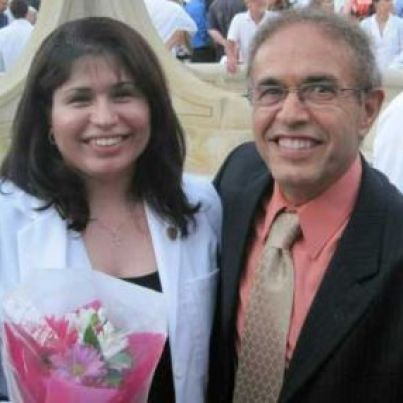

Kayla and her Dad at her white coat ceremony during the first week of medical school.