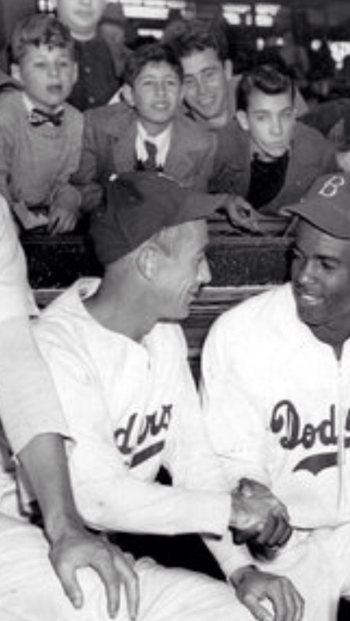

"Imagine," Eddie Dweck muses as he looks at The Photograph, "a kid going to a ballgame dressed in a suit and tie!"

You probably don't know Eddie Dweck, but you've probably seen him before. Because of The Photograph he has a cameo role in history. But history is a defiant and elusive thing. It will tell you that The Photograph Eddie Dweck is ruminating on is one of the iconic images of Jackie Robinson just before he stepped out of that Ebbets Field dugout and into history 66 years ago today.

Except it wasn't taken on April 15, 1947. And Mr. Dweck will also reveal to you that -- albeit in the mildest sense of the word -- the photograph was staged.

The kid looking at the camera, the kid Jackie Robinson seems to be looking at? Meet Eddie Dweck.

Eddie Dweck atop the Dodgers' dugout, Ebbets Field, April 11, 1947 (C) Corbis Images

12-year old Eddie and his pal Bobby Saltzberg from the apartment building on Ocean Parkway went to the first few of their sixth grade classes, then joined Eddie's first cousin -- also named Eddie Dweck -- and took the half hour subway ride to Ebbets Field. To see history? To see the Dodgers' first game of 1947! "It wasn't quite Opening Day," 78-year old Eddie says. "We just wanted to be there. We were fanatics about the Dodgers. That was the whole thing. I lived, slept, died with them."

The Dodgers' first game of 1947 -- the first one in Brooklyn anyway -- wasn't the world-changing National League opener whose anniversary we celebrate today. It was an exhibition game against the Yankees on Friday, April 11, 1947, and it drew 24,237 fans -- two Eddie Dwecks and one Bobby Saltzberg among them -- just 2,026 fewer than the 26,623 who did not fill the stands for the actual moment of history on a Tuesday afternoon four days later.

Having clarified history's erroneous conflation of Robinson's first game in a major league uniform in a major league stadium (April 11, when the photo was taken, when Robinson went hitless but drove in three runs, one on a fielder's choice and two on sacrifice flies) and his first official Major League Game (April 15), what was that part again about the photo -- a photo which nearly all the rest of us look at as we might look at an image of Abraham Lincoln in a crowd or at least Babe Ruth -- what was that about it being staged?

"Staged," he said again, and matter-of-factly. "We had maybe bleacher seats, the cheapest seats, and we trying to get to the Dodger dugout just like we tried to get to the Dodger dugout every game we went to. But there were a hundred photographers taking pictures of him. This was a momentous day. So they told the ushers 'let these kids come down, and lean over like you're trying to get his autograph.' And that's how we got down there. It was a matter of a few minutes, five minutes, ten minutes as I remember. Then we had to scatter."

So this was a kind of benign news management, as opposed to news manufacturing. There were kids trying to get to the Dodger dugout, they were hoping to get Jackie Robinson's autograph, and the photographers simply reduced to zero the chances against them getting to their destination. "With me, it looks like he's looking at me, that's the interesting part. Maybe I had a long hand or something!" I asked Eddie if he ever got the autograph. "No. It looks like he's signing something, but I don't think anybody got an autograph, not while I was there." But he got something better. "That picture was in The Brooklyn Eagle, and from The Brooklyn Eagle it was in Sport Magazine, and then it was in one of Jackie Robinson's books. But, man, I was in The Brooklyn Eagle!"

There was one detail that troubled Eddie Dweck. Where were his Cousin Eddie, and his pal Bobby? "I didn't go down there myself, that's for sure."

Steer away from Dweck's photographic odyssey for a moment for a larger question. Did he -- the 12-year-old-from-Ocean-Parkway-he -- understand what had happened? How one day baseball didn't allow African-Americans to play in the major leagues and then that day, that day, suddenly it did? "Yes. I knew that Jackie Robinson was the first negro player to play in the major leagues. So I knew it was significant but I didn't think of the social aspects. At twelve years old that's not on your mind. What's on my mind is 'he's going to be a great second baseman and maybe we can win a pennant.'" Here Eddie Dweck laughs. "But of course as I got older I started to realize, reading more about this, hearing about Dixie Walker and how he was against him all the time, and all the problems and how they couldn't even put him in the same hotel sometimes, he had to be in other hotels, you realize this was Rosa Parks in baseball."

This is where it would've ended, a story-and-a-half as it was. But then last Monday, Eddie Dweck phoned me and in his voice I could hear a touch of the excitement that must have been felt by his 12-year old self. "Keith, there's another photograph!"

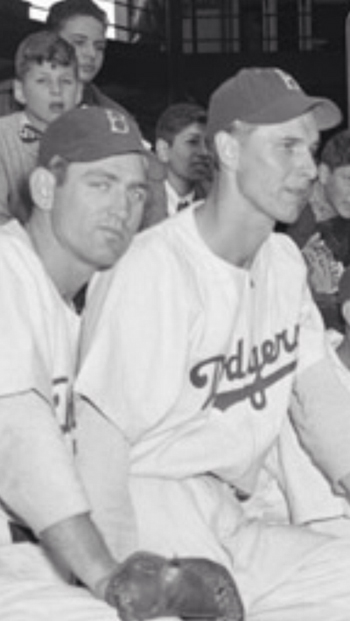

Eddie was in last Sunday's New York Times.

Per caption, New York Times Magazine 4/7/13: "The trailblazer Jackie Robinson in an Ebbets Field dugout in 1947 with members of the Brooklyn Dodgers." For some reason they didn't identify first basemen Ed Stevens and Howie Schultz or coaches Clyde Sukeforth, Jake Pitler and Ray Blades (surrounding Robinson). Or Eddie Dweck. (C) 2013 The New York Times

Oh, for crying out loud!

The New York Times Magazine review of the new Jackie Robinson movie 42 showed another photograph from April 11, 1947. Sure enough, almost dead center, same suit, same sweater, but this time just above and to the left of the beaming Robinson shaking hands with the Dodgers' acting manager Clyde Sukeforth, there, again, is Eddie Dweck.

"I hadn't seen that one before!" Apparently The Times had never printed it before, either. But there was more. "I found Bobby Salzberg! He's next to me, in the bow tie!"

Lower left: Clyde Sukeforth. Lower right: Jackie Robinson. Upper left: Bobby Saltzberg, Eddie Dweck. (C) 2013 The New York Times

Seeing Bobby also rattled something loose in Dweck's memory. "Now I know where my cousin Eddie was. It was Passover. He was at our seats, protecting the food! And protecting the seats, for that matter."

Too bizarre for words, no? The unexpected thrill of getting to see yourself in a new photo in your local newspaper at age 12 in 1947, and then the again unexpected thrill of getting to see yourself in a new photo in your local newspaper at age 78 in 2013 -- with both photographs from the same event?

It gets stranger still. Months into this process and a second photo having turned up and still nobody had done an image search for something as simple as "Jackie Robinson Dugout."

Sure enough, sitting on the website Biography.Com: Dweck/Jackie Robinson Photo number three:

Original caption, source unknown: "Members of the Brooklyn Dodgers and their new coach pose in front of their dugout before an exhibition game with the New York Yankees. The team has a new manager and new Negro star player from Montreal, Jackie Robinson." It also had a great fan, Eddie Dweck. Look to the left of the biggest guy, first baseman Howie Schultz.

Eddie Dweck wasn't kidding when he said there were a hundred photographers on the field clamoring for photographs of Robinson in the dugout. And there is a certain poignance in these two images that Eddie -- clearly the Zelig of Robinson's first day of Ebbets Field -- hadn't seen before. In this third shot, he and Bobby are positioned around the only other two players in the pictures: Ed Stevens and Howie Schultz:

(L to R) Bobby Saltzberg, Ed Stevens, Eddie Dweck, Howie Schultz.

Ed Stevens and Howie Schultz were the first basemen who would be displaced by Robinson.

It had been Schultz who had worked with Robinson throughout spring training to adapt to that position -- which Robinson had never played before -- even though Schultz knew it would probably cost him his job. Robinson, Branch Rickey, Sukeforth, Pee Wee Reese, even the walkout-threatening Dixie Walker got the headlines. But Schultz and Stevens simply uncomplainingly gave way to the better man.

At the moment the photographers captured them and Eddie and Bobby, Stevens and Schultz had exactly seven more games left between them as Dodgers, and only 375 more games left as big leaguers. Stevens would be sent out to the minors before Robinson would make his official debut the following Tuesday, and Schultz would linger as Robinson's sub and instructor until he was sold to the Phillies on May 10th. He would have a little more time in the sun (and in sports integration history) as a member of the 1952 NBA Champion Minneapolis Lakers, who won the first Finals ever to feature an African-American player, Sweetwater Clifton of the Knicks.

On the other side of Robinson (shaking Robinson's hand in the Times shot) is Clyde Sukeforth, who had just taken over as acting manager after the suspension of Leo Durocher. Sukeforth -- who helped to scout Robinson for the Dodgers originally -- would manage Robby's first game, and win it, and his second, and win that one, too. Those would be his only games as a manager, and his only other imprint in baseball history would be as the Dodger bullpen coach who in the 9th inning of the third game of the 1951 National League special playoffs against the Giants infamously led manager Chuck Dressen to conclude that Ralph Branca was his best asset to face Bobby Thomson because the other pitcher whose warm-up he was supervising, Carl Erskine, was "bouncing his curve."

Thus the memories the autograph photo evokes are not all happy ones. When I pointed out to Eddie that apart from him and Robinson the image also shows Branca, he said he cried all day after Branca gave up Thomson's home run four years later. Shortly after that Dweck actually attended one of the famous Dodger tryout camps at Vero Beach ("No expenses paid," he laughs. "I'll pay you to play. Such was the devotion") but did not cross paths with Robinson there. And within a decade the Dodgers would prove that an African-American was like any other player in baseball: he could be unceremoniously dumped no matter what his contributions to team or time. And as they traded Robinson to the hated New York Giants, they were already negotiating for the event that would prove that a Brooklyn fan was like any other in sport: he could be unceremoniously dumped if a better deal loomed westward. "When they did leave, I lost total interest. I didn't follow them to Los Angeles. Even baseball in general, I kinda got turned off. It really hurt me."

In some indirect way, it hurt him to the degree that until last month, he hadn't owned a copy of The Photograph since that edition of The Brooklyn Eagle came out. That is even stranger when you consider what Eddie Dweck does for a living. Today he is the with-it, energetic co-proprietor of Studio 57 Fine Arts on West 57th Street in New York, and can use the photograph to prove to doubters that he wasn't in diapers in 1947. The gallery features not just high end art and some of the metropolitan area's avant-garde painters, but has also always offered a great supply of historical baseball photographs, many of which are at the level of sophistication and eccentricity of a shot of Babe Ruth pitching for the Yankees and a variety of shots of Dweck's beloved Ebbets Field. More over, I've been one of his customers since 1997 and last January was the first time he ever mentioned that it was him in the Robinson/Fans photograph.

"Well," Eddie Dweck says with a measure of contemplation that dissolves into a laugh. "You didn't ask."

Eddie Dweck holds a copy of "The Photograph" at Studio 57 Fine Arts gallery, March 2013

Update: The Baseball Hall of Fame combed its files and there are now SIX different photos with Eddie front and center.

This post originally appeared at Baseball Nerd.