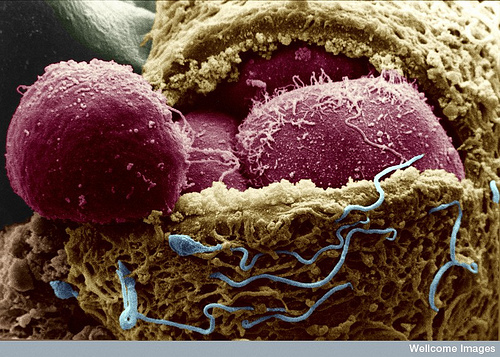

From the smear campaign against Planned Parenthood to the recent uproar about Sofia Vergara, everyone seems to be talking about the fate of human embryos. This conversation is no longer a private one between a woman and her doctor it's now in the legal domain of lawyers and courtrooms. Meanwhile, with the help of Photoshop, conservative Catholics and Christians have been busy rebranding the visual image of conception. We no longer think of embryos as just a cluster of cells that might (fingers crossed!) become a baby; we're being conditioned to think of them as a fully formed human.

But should we take it as a matter of faith that an embryo is truly a person?

I am not a lawyer or a doctor -- but I did have a frozen embryo. When my son was pushing two and my husband was planning his military retirement, we needed to figure out what to do with my frozen cells. While personhood debates raged on a national level, thousands of frozen embryos, mine included, remained safely tucked away from the political fervor in their test-tube bassinets.

We had planned to use the embryo at some point but with our life in flux the timing seemed wrong. Logistically, it would have cost a small, uninsured fortune to move the specimen to a lab closer to our new home. Rather than leave my cells in frozen perpetuity and pay hundreds of dollars a year for storage fees, we decided to thaw our potential offspring and transfer my embryo into my uterus.

For weeks prior to the procedure, I injected the necessary hormones to prepare my body to re-accept its fertilized egg. I prayed said body would instinctively recognize her absentee cells, spontaneously throw open the cervical door, and welcome the blastocyst home. But before the actual transfer, my embryo needed a lift. "Transport it yourself," my doctor said when I ask how physically to move the specimen from the lab up the road to his office. "They charge a hefty delivery fee." What I discovered was retrieving your frozen embryo is, strangely, like running any errand. "Before you sign, we'll bring out the specimen, so you can identify it as yours," said the lab assistant when I entered her office. Exactly how am I supposed to identify a ball of cells as my own? Do I look for hints of reddish-brown hair and freckles, Harry's birthmark? It turned out to be all about the paperwork, standard legal precautions.

A tech entered the room, holding what looked like a small, old-fashioned milk canister. He placed it gently on the table and firmly turned the cap. The jug burped a cloudy white breath. "Liquid nitrogen," he explained. "To keep the specimen frozen and get you down the road." The cap lolled sideways like an infant's head as he, using tiny forceps, hoisted a small tube from the canister's belly. As with any old file, there was my name, social security number and collection date typed clearly on the label. I considered the clear glass vial before me. A chalky mass hung suspended in the center as if someone froze snot in the middle of an ice cube. I stared into the tube, wishing it had all the powers of a crystal ball, but I didn't imagine a fetus in my womb or an infant in a crib. I saw before me the arduous journey that this little booger needed to make. "It's mine." I said, using my business voice.

"Excellent. You also have to clear up a $500 storage bill, plus the $75 for the tank rental. Please sign here." I wrote a check and signed my name. Did I really just pay $600 to get my egg out of hock? Then, the tech handed me my -- my canister? My blastocyst? My frozen snot? "Hold it upright," he cautioned. "Oh, and you'll be charged a $100 if you fail to return the canister."

Once in the passenger seat, I gripped the metal vessel maternally between my legs as though if I hugged hard enough a thawed baby would emerge. "Should we have belted totsicle in an infant seat?" I asked my husband. "Don't be ridiculous!" he answered. "Well, if we were in Texas -- it could be the law. Some believe that this is an actual person." Part of me wanted to hang on to the slim chance that inside this canister was an actual person. In the backseat, our toddler snoozed in the mid-morning heat. This might be the closest we ever come to being a family of four.

I shut my eyes and imagined taking my cylindrical cooler to the beach, propping it up on a towel and, like a good mother, slathering it in sunscreen. I considered what this canister represented, a kind of traveling womb -- not of the warm, pink, squishy sort, but rather a sterile pod; inside the possibility of life, safely frozen in time.

My traveling womb in hand, I walked into the doctor's waiting room and was met with the flat smiles of the fertility challenged. The stainless can on my arm could have been a designer purse. No one noticed. With my tot securely snuggled inside its new freezer, I was handed back the empty jug. Not surprisingly, the weight was unchanged; microscopic cells are not heavy. The insufferable weight comes from what these cells represent: the fleeting chance a tot will take hold and, like a sticky-fingered child, cling to the walls of my uterus for dear life.

The morning of my transfer, I felt giddy with confidence as we entered the doctor's office. In my mind it was only a matter of time before a full-fledged infant filled the baby seat. As I reclined on the exam table, I joked with the doctor that this child would be my son's twin -- three years removed. They were, after all, conceived on the same day. Smug in my motherhood, I watched on the monitor as the doctor snaked the pipette up and into my uterus. Like a flower's stamen, a single pollen bubble floated away from the anther.

At 3 a.m., I woke to a slight trickle of perspiration down my breast and felt the dull ache of the swollen mammary as I shifted my sleepy body -- the first signs of a pending period. I'd failed. Maybe my womb is prickly -- a briar patch -- allergic to fertilized eggs. Even when slipped into the hormonally pristine pocket by the skilled hand of Dr. M., my womb sneezed and blew that sucker out. Period. End of sentence. End of cycle.

I sat awake that night, staring out the window out at a waning moon, wondering how an embryo's rights could ever supersede a woman's. Laws are already popping up in many states. And while the arguments about fetal tissue research and line items in divorce papers continue, my greatest concern, I realized during those still morning hours, is truth. It's easy to forget while screaming about politics or religion that even when we have faith that our frozen embryos will become babies, life is not a guaranteed result. In reality, that cluster of cells may silently diminish, seeping out of your body like a dropped cherry ice-pop melting on a hot summer sidewalk.