Negotiations are underway in Panama, the last gathering of climate diplomats prior to the big Durban Climate Conference at the end of the year.

Last June Yvo De Boer, former head of the UN climate convention and for years THE stalwart champion of the negotiating process, commented that "this process is dead in the water, it's not going anywhere." I generally don't repeat self-defeating soundbites, but his words did seem to echo a sense within the climate community that perhaps more immediate progress could be made in a bottom-up approach at the national or business level.

I recently asked current UN climate head Christiana Figueres what she makes of this. She told me a bottom-up approach is not mutually exclusive from a top-down effort to get a treaty:

"The first encourages countries to seek the opportunities that are most evident at the moment in order to start the process of the transformation, but the top down is necessary to ensure that the collective effort responds to the requirements of science. Think of it as paying a bill. We can start making payments in amounts that are possible right now, but in the end we have to pay the full bill, or we will pass it onto our children."

So here are seven reasons why we still need to fight for a fair, ambitious and legally binding, international agreement in order to pay that bill on behalf of our children:

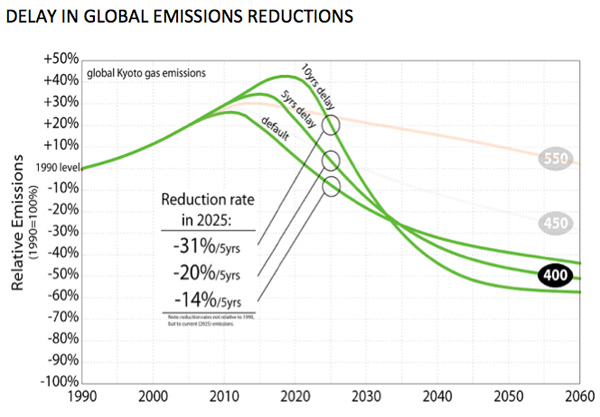

1) It's urgent. We need to get the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere to stabilize at 350 parts per million or lower. We have currently overshot the mark at 390 -- so we need to drastically reduce our emissions, and fast. Global CO2 emissions need to peak within the next few years, and then steeply decline from there on out. The longer it takes to reach that peak, the steeper the reductions will have to be in subsequent years. The graph below, although several years old now, visually demonstrates just how much harder it will be to deal with the problem if we don't move quickly.

Courtesy of M. Meinshausen, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK)

2) It will create long-term certainty for business investment. The International Energy Agency has estimated that $26 trillion in capital investment is needed to meet global energy demand through 2030. Clearly most of that investment will be made by the private sector, and businesses repeatedly say they need long-term certainty to guide those investments. For example, will carbon polluters continue to get a free ride, or will a binding emissions reduction target result in a high price on carbon? The answer to that question matters a lot when it comes to investing in energy infrastructure. And while renewables make sense in their own right, investment in large-scale energy efficiency doesn't generally happen without regulatory or financial incentives. Doing this one country at a time is too slow, and...

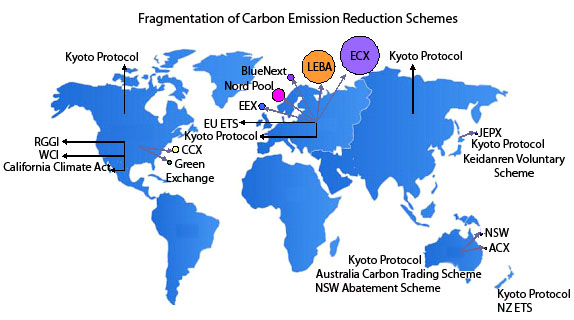

3) It will be more economically efficient for countries to do it all together. Whatever you may think of carbon markets as a means of reducing emissions, they are having an impact. But there is a patchwork of different schemes, which is not nearly as economically efficient as a more comprehensive scheme would be.

4) Collective action is needed. While countries like the Maldives set an important example by moving towards carbon neutrality even in the absence of a binding law requiring them to do so, most countries are not as noble. Many will want to know that their competitors are taking comparable action before they make the deepest cuts in emissions. Signing, ratifying and passing legislation to implement an international agreement with effective compliance and enforcement mechanisms demonstrates a longer-term commitment not easily undone following the next election.

5) Unpopular decisions may be more palatable if other countries are taking them as well. Misinformation campaigns by the fossil fuel industry have whipped up populous opposition in several countries which have tried to pass legislation reducing CO2 emissions. It's time to wage the mother of all wars against these special interests, and this will be easier if they can't play one country off against another.

6) Who will otherwise pay for adaptation? It's too late to halt climate change altogether. The Netherlands, where I live, learned about storm surges the hard way when nearly 2000 people lost their lives in the flood of 1953. The Delta Works -- a €5 billion system of barriers and dikes -- was constructed to ensure this never happens again. How will Bangladesh, a country which did little to cause the problem, ever be able to provide their citizens with the same degree of protection? And coastal flooding is only one of the many problems caused by climate change. No-regrets measures to improve energy efficiency and scale up renewables will not take care of this problem.

7) We are morally obligated. For the sake of intergenerational responsibility, climate justice and social equity we must effectively and comprehensively address the climate problem. And for the reasons described above, this will only happen through an international agreement.

- Secure the future of the Kyoto Protocol with a second commitment period. It's the only legally binding agreement we have for now.

- Obama administration officials: stop criticizing the Kyoto Protocol until you have something more to offer. If you can't say anything constructive, don't say anything at all! And everyone else: stop listening to the US on the subject of Kyoto.

- Europe: up your game by confirming your unconditional intention of signing up to a second round of Kyoto commitments. It's a no-brainer -- it makes economic, political and diplomatic sense to do so.

- Agree a process and timeline to finalize a legally binding deal that includes all major emitters while recognizing the common but differentiated responsibilities between countries at different stages of development.

- Finance for developing countries is a key lever in breaking the deadlock. Despite the recession, there are many innovative proposals on the table which you could adopt: a tax on shipping and aviation fuels, a financial transaction tax, and the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies to name a few.

In 2010, CO2 emissions went up by 5% -- the fastest rise in the last 20 years. The big emitters need to start talking seriously about increasing their level of ambition, and must stop obstructing progress in the negotiations. And the rest of us need to hold our governments accountable to deliver the necessary agreements sooner rather than later.