Is Senator Bernie Sanders (DS-Vt.) a Communist? So says the New York Post, Donald Trump, and a confusing mix of politicos left and right trying to undercut him as a candidate for President of the United States.

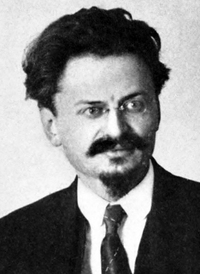

The fact is, no label in American politics had been used more destructively or cavalierly over the years than "communist." Actual true-blue communism, a radical strain of Marxism expounded by Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky after the 1917 Russian Revolution, has a dark, scary history: totalitarianism, purges, mass murders, espionage, and global oppression. Calling someone a "Communist," particularly at the height of the Cold War during the 1950s and 1960s, amounted to accusing them of treason, child beating, or worse.

But most of the people tarred over the years as "communist" by generations of demagogues had nothing to do with any of this. Particularly socialists. And this brings us to Bernie Sanders. No, Bernie Sanders is no communist. In fact, in America especially, socialists like Sanders have often been communism's worst enemies.

Democratic socialists -- the kind Bernie Sanders embraces -- have a long history in this country. At their popular height a century ago, they had achieved wide acceptance in the American mainstream. By 1917, the American Socialist Party had won elections all across the country. Two socialists had sat in the United States Congress, socialists had held mayoral offices in 56 towns and cities including Milwaukee and Schenectady. Socialists held over thirty seats in state legislatures from Minnesota to California to Oklahoma and Wisconsin, plus dozens of city council and alderman chairs.

The Socialist Party then had over 110,000 dues-paying members and about 150 affiliated newspapers and magazines. Its flagship monthly Appeal to Reason reached almost 700,000 subscribers; its New York outlet, the Yiddish-language Jewish Daily Forward, had a daily circulation topping 200,000 copies, rivaling even the New York Times.

In 1912, the party's presidential candidate, Eugene V. Debs, won almost a million popular votes, about six percent of the total, against a field that included Woodrow Wilson (Democrat), William Howard Taft (Republican), and Theodore Roosevelt (Bull Moose). Socialist politicians had become so accepted that one party leader, New York's Morris Hillquit, met numerous times with President Woodrow Wilson in the White House without it raising an eyebrow.

The Socialist Party platform of that era brimmed with ideas later to become staples of modern America, including:

- A graduated income tax;

- Limits on child labor;

- A right to strike for workers;

- School lunches for poor students;

- Mine and factory inspections;

- Regulation of financial markets;

- Public works jobs for the unemployed;

- A minimum wage and limited work week,

- Public defenders to assure fail trials for poor people; and

- Public ownership of local industries like street cars and subways.

As Marxists, socialist leaders still preached "revolution," but more as a metaphor for fundamental change through winning elections and passing laws.

But two factors conspired to end the Socialist's Party's golden age in America. First was the Party's staunch opposition to American entry into World War I. Second was its hard-line stance against communists, radicals, and the labor movement's violent fringe.

Socialist leaders of that era had high hopes of becoming a major third party in America -- must like socialists in France today -- perhaps even displacing Tammany Hall as New York's main benefactor of immigrants and the working poor. But they recognized that they could never achieve this goal and win public trust so long as they remained stigmatized by violence and criminality. That's why, in 1912, Hillquit, the New York leader, led a successful effort to expel William "Bill Big" Haywood, leader of the more-radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies") from the Socialist Party's executive committee after Haywood publicly endorsed "sabotage" as a labor tactic.

Perhaps the starkest confrontation came in March 1917 when Leon Trotsky, the famous Russian revolutionary who had found temporary refuge in New York City for about three months before returning home to help lead the Bolshevik Revolution, decided to lead a group of New York leftists in challenging the Socialist Party leadership. Trotsky had immersed himself in local politics that winter, and he convinced his followers to demand that the Socialist Party launch illegal general strikes to physically block America's imminent entry into the First World War -- a step that would have virtually criminalized the entire movement.

Morris Hillquit, the party leader in New York, had to face down Trotsky -- no shrinking violet -- in a series of tense confrontations culminating in a raucous public meeting in Harlem where Trotsky insisted that party members publicly vote on his proposal. Hillquit defeated Trotsky that day by a narrow margin of 101 to 79. But the clash -- described in my new book Trotsky in New York 1917: Portrait of a Radical from Times Square to Petrograd, due out in September -- left the party fatally fractured.

Two years later, in 1919, Hillquit again had to face down an attempt by radicals to seize power and, this time, he had no choice but to expel almost 70,000 left-leaning party members, more than half the total, to preserve the Socialist Party's moderate, democratic majority. It was these expelled socialists who went on that year to form the new American Communist and Communist Labor Parties in direct coordination with Moscow.

The American Socialist Party never recovered from these internal battles as an effective political force. Nor did it escape the stigma of radicalism. Socialists found themselves targeted during the Red Scares of the 1920s and 1950s right along with communists. In 1920, the New York State legislature expelled its last five legally-elected Socialist members and never allowed them to return. This move was denounced by the New York Bar Association, Republican presidential candidate and future Supreme Court Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, and even Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, author of the notorious anti-red Palmer raids.

Socialists maintained their anti-communism all through the following decades.

Much of their early platform -- the social safety net, financial regulation, workplace safety, school lunches, and the rest -- ultimately was adopted by mainstream political parties and enacted into law, particularly during the New Deal of the 1930s. Today, we take much of it for granted as essential parts of American life.

Bernie Sanders' version of Democratic Socialism fits easily in this long moderate tradition. Those who try to stigmatize him by shouting "Communist!" are engaging in scare tactics and nothing more. Sanders is no communist, and in America, we have all been socialists for years.

# # #