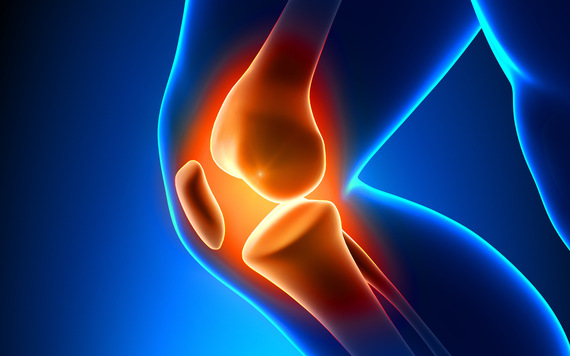

New studies have shown that when a meniscus tissue is torn in the knee, enzymes and factors are released, creating a degradative soup that affects healing and eventually leads to arthritis.

Injury to joint tissues used to be thought of in primarily mechanical terms. Torn ligaments led to instability; a torn meniscus led to arthritis, both from the window wiper effect of the tissue in the joint and the force concentration from losing the shock absorber; impact injuries led to bone and cartilage death. [1]

We now understand that this thinking was far too narrow. Papers presented at the 29th Meniscus Transplant Study Group meeting in Las Vegas recently, demonstrated that when a meniscus tissue is torn, pro-arthritis enzymes and factors are released, which stimulate the synovial lining cells of the joint to go into overdrive. The tissues talk to each other. They are biologically, not just mechanically, active. [2]

The enzymes and factors released into a joint after injury produce a degradative fluid. Degradative means that the compounds break down tissue, inhibit healing, cause swelling, and eventually arthritis. When people complain of joint swelling, the fluid is degradative and leads to more injury over time. Healing occurs when the swelling resolves and the body lays down new tissues. [3]

This new biologic understanding of tissue injury is now leading to novel approaches to repair. Most importantly, injured tissues need prompt repair. Left unrepaired, they continue to stimulate the surrounding tissues, leading to the cycle of breakdown and arthritis.

Prompt repair can now sometimes mean not just surgical repair but injections of stem cells. Data presented from the group in Tokyo, led by Dr. Ichiro Sekiya, convincingly demonstrated limited meniscus repair with injections of high numbers of synovial stem cells alone. Stem cells migrate to the site of injury and induce repair both directly and also indirectly by releasing growth factors and changing the degradative environment to an anabolic one. [4]

The importance of the chemical environment of the joint, and its influence on healing, has wide ranging implications. Drugs we take to reduce inflammation may sometimes inhibit healing, as non-steroid anti-inflammatory, such as ibuprofen, have been shown to do [5]. Arthritis may in fact be preventable if we are able to stop the production of the enzymes early after injury. A new compound named IL1-Ra or Anakinra was presented at the meeting that did just that in an unrepaired, displaced fracture that normally would have gone to severe arthritis. [6] Other compounds such as glucosamine and chondroitin also induce the production of normal joint lubrication and stimulate matrix repair. [7] Their mechanisms of action may now be more understandable and accepted as valuable therapeutic agents.

The biologic era of joint repair is evolving so rapidly that removing injured tissues may soon be a surgical procedure of the past. Repairing, regenerating, and replacing tissues with natural tissues as opposed to artificial materials, is the path keeping biologics firmly ahead of bionics in orthopedics.

References

1. Pavlov, H., Dalinka, M. K., Alazraki, N., Berquist, T. H., Daffner, R. H., DeSmet, A. A., ... & McCabe, J. B. (2000). Acute trauma to the knee. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Radiology, 215, 365.

2. Stone, A. V., Loeser, R. F., Vanderman, K. S., Long, D. L., Clark, S. C., & Ferguson, C. M. (2014). Pro-inflammatory stimulation of meniscus cells increases production of matrix metalloproteinases and additional catabolic factors involved in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 22(2), 264-274.

3. Chockalingam, P. S., Glasson, S. S., & Lohmander, L. S. (2013). Tenascin-C levels in synovial fluid are elevated after injury to the human and canine joint and correlate with markers of inflammation and matrix degradation. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 21(2), 339-345.

4. Shen, W., Chen, J., Zhu, T., Yin, Z., Chen, X., Chen, L., ... & Ouyang, H. W. (2013). Osteoarthritis prevention through meniscal regeneration induced by intra-articular injection of meniscus stem cells. Stem cells and development, 22(14), 2071-2082.

5. Pountos, I., Georgouli, T., Calori, G. M., & Giannoudis, P. V. (2012). Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs affect bone healing? A critical analysis. The Scientific World Journal, 2012.

6. Bresnihan, B., Newmark, R., Robbins, S., & Genant, H. K. (2004). Effects of anakinra monotherapy on joint damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Extension of a 24-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. The Journal of Rheumatology, 31(6), 1103-1111.

7. Bruyere, O., & Reginster, J. Y. (2007). Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate as therapeutic agents for knee and hip osteoarthritis. Drugs & aging, 24(7), 573-580.