Photo Credit: Photo by Kim Dramer

In his short novel, Washington Square, Henry James wrote about New York women of the Gilded Age; elegant ladies who strolled the sidewalks of the city's shopping district, Ladies' Mile.

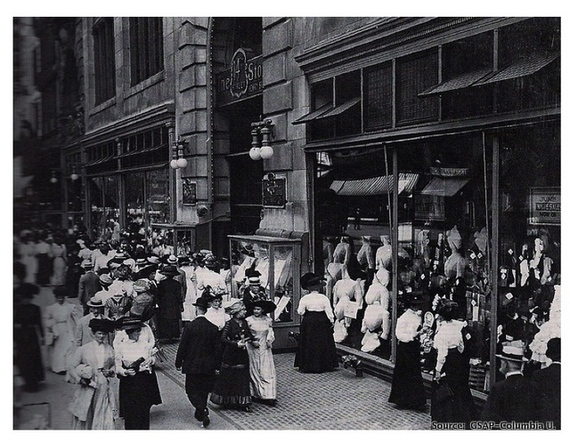

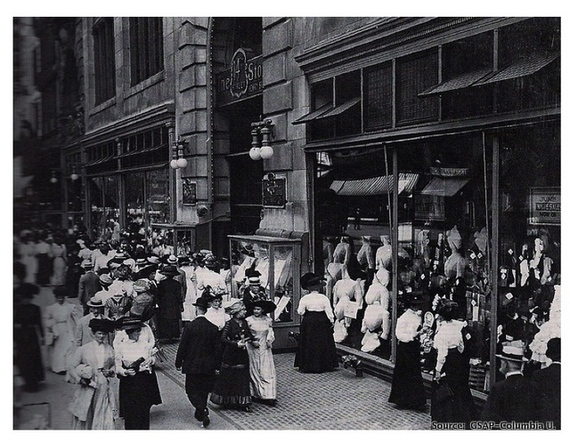

Photo Credit: Courtesy GSAP, Columbia University

These New York women admired window displays of shirtwaists, an elegant button-down blouse with rows of tiny and elaborate tucks. The shirtwaist was favored by New York women as a symbol of chic modernity. But the silhouette of fashionable ladies came at a price paid by their downtrodden sisters, immigrant women living in the city's tenements. These newest New York women worked long hours for low wages in the city's notorious sweatshops.

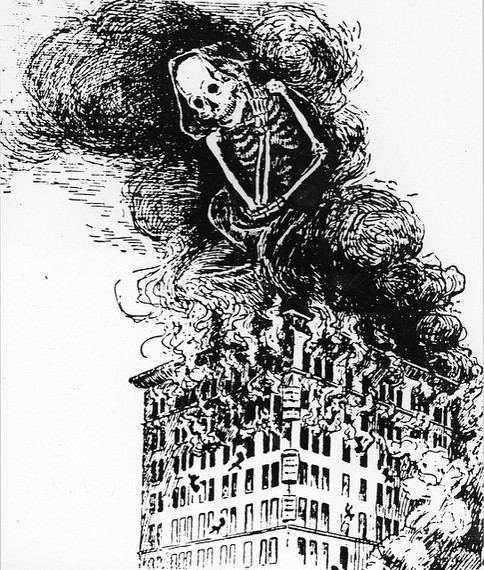

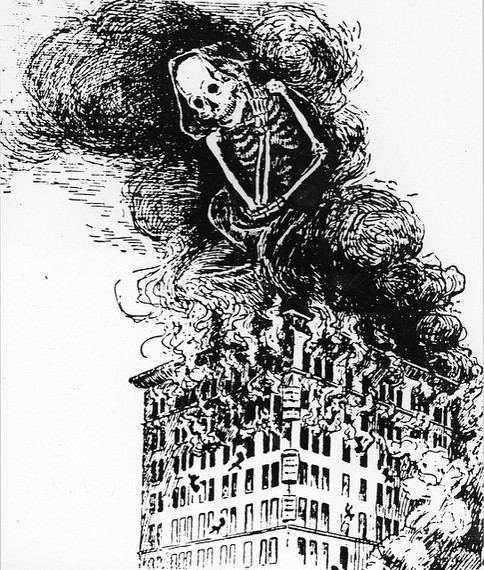

Image Credit: Dragonflysixtyseven via wikimedia.commons

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was one such garment factory producing shirtwaists. Workers at Triangle were considered fortunate as the factory was better than the brutal tenement sweatshops. Such a large and successful company was not likely to lay off workers during slow periods. Located on the 8th, 9th and 10th floors of the Asch Building (now owned by NYU and known as the Brown Building), the women worked long hours for low wages. They worked behind cramped rows of sewing machines and were surrounded by baskets of fabric, oil soaked machinery, flying thread and cotton scraps. It was a recipe for human tragedy.

On March 25th, a Saturday rich with the promise of spring and renewal, that tragedy struck. A fire broke out in the cramped and cluttered workroom floor, quickly consuming the factory in flames. The fire and smoke killed 146 workers, mostly Italian and Jewish women who walked to factory from the nearby tenements of downtown New York.

Image Credit: Kheel Center for Labor Management and Documentation and Archives, Cornell University

Some of the women fled to the factory's single fire escape. The structure collapsed under their weight, spilling them onto the sidewalk below. When the fire company arrived, their ladders only reached the 6th story. In desperation, women jumped, hoping to grasp the ladders below. As the flames grew higher, groups of women, some family members, joined hands and leapt to the deaths, ending their lives on the sidewalks below.

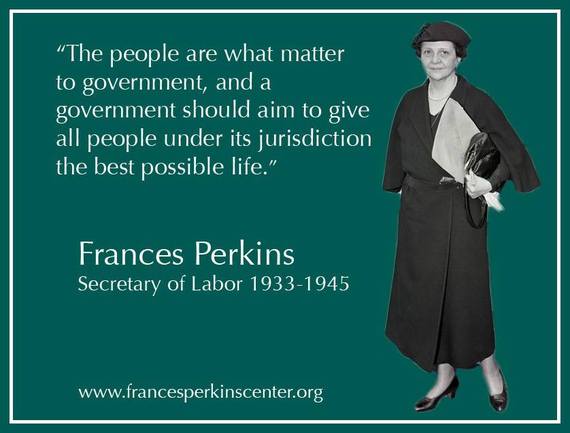

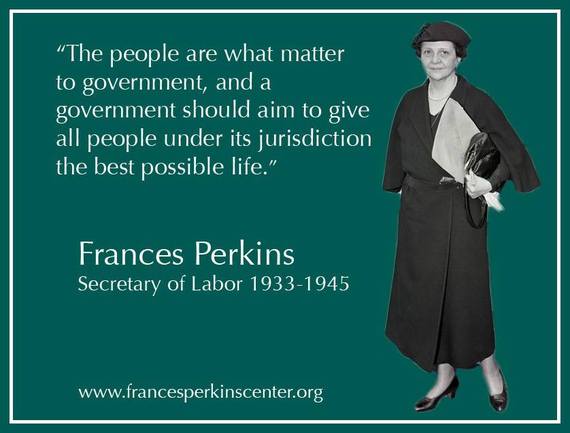

Spectators who had been out enjoying the afternoon in Washington Square Park watched in horror as the women jumped, fell and crumpled on the pavement. Frances Perkins was among the reluctant audience members to the spectacle that day. That day, she vowed to work to ensure such a performance was never repeated. Perkins later served as U.S. Secretary of Labor under President Roosevelt (1933-1945). She worked with FDR throughout his presidency, improving conditions for American workers.

Image Credit: Courtesy francesperkins.org

The deaths of those 146 New York women galvanized a national movement for social and economic justice. Led by Frances Perkins, American workers achieved standards that become a model for the world. But today's laborers continue to battle dire working conditions. The question now: How can we bring the lessons of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire back into practice today?

Photo Credit: Courtesy University of Iowa Press

Those sidewalks near Washington Square Park, where the bodies of women lay broken, provided the answer for New York multimedia artist, Ruth Sergel. For Sergel, who grew up near the site of the Triangle Fire, the answer has been to fuse art, activism, and collective memory to create a large-scale public commemoration. See You in the Streets, Sergel's forthcoming coming book, documents her efforts to devise memorials for the Triangle Fire that invite broad participation and incite civic engagement.

Sergel's public art intervention, Chalk, extends an invitation to all New Yorkers to remember the 146 victims of the fire. Each March 25th, participants in Chalk spread out across the city, mostly in lower Manhattan. They use colorful sidewalk chalk to inscribe the names and ages of those 146 victims in front of their former homes. Using the sidewalks of New York as both a medium and a place, Chalk celebrates the lives of these New York women rather than their deaths in what Sergel calls a "community intervention." For one day each year, the lives of these New York women, their hopes and dreams, come alive once again, linking their lives with our own.

Photo Credit: Photo by Kim Dramer

Chalk is an informal network of participants that has grown through word of mouth, press coverage or simply those who seeing the project in the streets have sought out more information. Sergel sums up the yearly efforts: "The chalk will wash away but the following year we return, insisting on the memory of these lost young workers."

To participate in Chalk, go to Ruth Sergel's web site streetpictures.org.

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

It's Another Trump-Biden Showdown — And We Need Your Help

The Future Of Democracy Is At Stake

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

Your Loyalty Means The World To Us

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

The 2024 election is heating up, and women's rights, health care, voting rights, and the very future of democracy are all at stake. Donald Trump will face Joe Biden in the most consequential vote of our time. And HuffPost will be there, covering every twist and turn. America's future hangs in the balance. Would you consider contributing to support our journalism and keep it free for all during this critical season?

HuffPost believes news should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay for it. We rely on readers like you to help fund our work. Any contribution you can make — even as little as $2 — goes directly toward supporting the impactful journalism that we will continue to produce this year. Thank you for being part of our story.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

It's official: Donald Trump will face Joe Biden this fall in the presidential election. As we face the most consequential presidential election of our time, HuffPost is committed to bringing you up-to-date, accurate news about the 2024 race. While other outlets have retreated behind paywalls, you can trust our news will stay free.

But we can't do it without your help. Reader funding is one of the key ways we support our newsroom. Would you consider making a donation to help fund our news during this critical time? Your contributions are vital to supporting a free press.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our journalism free and accessible to all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you'll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.