Fortunately, the reason for Memorial Day in the United States is not overlooked. Celebrations tend not to overshadow the fact that this holiday is a day of remembrance for the millions of individuals who serve the United States, and sadly, the millions that have died for the United States. It honors those living and those departed so they themselves, their sacrifice, and the reasons for their sacrifice are not forgotten. Some of the reasons that they served were to protect and uphold our most sacred values and principles, such as "peace," "security," "rule of law," and "justice." These same principles reside by word and sentiment in America's most cherished documents: the U.S. Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

These precise words and sentiments are also found in the Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court (ICC), the first permanent international tribunal created to prosecute genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. On July 1, 2012, the ICC celebrates its tenth anniversary. All three of these documents share a gravity of purpose and achievement, each breaking new ground in order to attain the previously unthinkable.

The Declaration of Independence claimed the undeniable rights of humans, both individually and collectively, to protect their interests and create for themselves. Celebrating its 225th anniversary this year, the U.S. Constitution showed the power of the written document to establish a just rule of law and to strike a balance of governmental powers. The Rome Statute recognized the duty of sovereigns, also both individually and collectively, to act when unimaginable horrors are visited upon the human family, and prosecute their perpetrators with the utmost respect for due process. The Rome Statute at its core and in practice honors the tenants of these American precedents.

In this tenth year of the ICC, it is an appropriate time to take stock of the Court's progress in its primary mission: end impunity through the just rule of law. Thus far, assessments of the ICC are varied to say the least, from the unfair and unrealistic, and the critical, yet contextual, to the reasonable and measured. How the Court can be both satisfactory to some, a concern to others, and both to many is a matter of differing politics and viewpoints as well as a testament to the Court's mixed record. For some, the ICC is failing as it took six years to finish its first trial, several Prosecution indictments failed to receive judicial approval due to insufficient evidence, and the ICC's Africa-centric caseload shows that it is a neo-colonial institution employing "selective justice" to eliminate disfavored African leaders. Others respond by pointing out that the Pretrial Chamber's pushback on Prosecution indictments proves that the Court's safeguards against political or questionable prosecutions are working. Further that many of the African situations at the ICC are the product of self-referrals by African states themselves or UN Security Council referrals. More importantly, supporters of the ICC argue that the Court has quickly attained legitimate status on the international stage, instead of being relegated to irrelevance as predicted by some.

The assortment of opinions and analyses of the ICC will continue through this year of reflection, and this exercise is to be embraced. The first milestone anniversary of the Court offers an important opportunity for ICC stakeholders to convene and have honest discussion about where the Court succeeded, and where more work is to be done. The recent Stanford Law School's Conference on the tenth Anniversary of the ICC was the first such conference in the United States where frank conversation could occur. This conference entitled "ICC Turns Ten: Reviewing the Past, Assessing the Future" brought together an impressive lineup of panelists from the ICC's principal organs -- the Presidency, the Registry, and the Office of the Prosecutor -- as well as from the United States government, academia, and civil society.

Prof. Allen Weiner, Prof. Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar, H.E. Judge Cuno Jakob Tarfusser, H.E. Justice Mrs. Silvana Arbia and Prof. Ruth Wedgwood - Stanford Law School

Prof. Allen Weiner, Prof. Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar, H.E. Judge Cuno Jakob Tarfusser, H.E. Justice Mrs. Silvana Arbia and Prof. Ruth Wedgwood - Stanford Law School

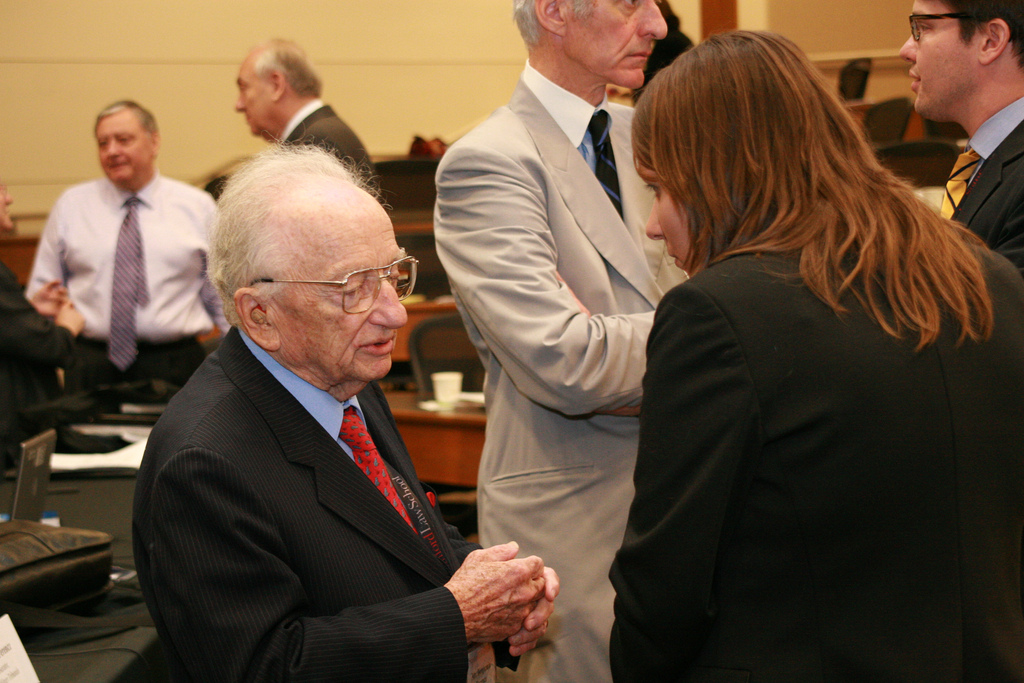

Ben Ferencz, the last remaining Nuremberg prosecutor and pioneer of international criminal law, was also in attendance.

Ben Ferencz - Stanford Law School

Ben Ferencz - Stanford Law School

Being the first such conference in the United States, the event naturally analyzed both the record of the Court itself and also its relationship with the United States, who remains a non-State Party to the Rome Statute. On both accounts, the Stanford conference was noteworthy for not only highlighting the Court's accomplishments and candid identification of problems, but of more significance, discussion on innovative solutions to these issues.

The American Bar Association (ABA), a co-sponsor of the Stanford conference, took the opportunity to present its new ICC Project, an endeavor that ICC President Sang-Hyun Song "commended" as well as the conference and its organizers. In his speech, the Chair of the ABA Center for Human Rights, Michael Greco, laid out that the Project's purpose was to turn ABA's strong set of policies on the ICC as passed by its House of Delegates into "concrete action," namely positive action on the burgeoning, but uncertain U.S.-ICC relationship. As the world's largest voluntary professional organization with 400,000 members, the representative of the American legal profession, and with its broad-based coalition of partners, Mr. Greco made clear that the ABA was "well-positioned" to take up this cause.

As for details, Mr. Greco described that the ICC Project aims to strengthen, regularize, and broaden the U.S.-ICC relationship through assorted forms of engagement, in particular engagement among and between legal practitioners, government representatives, ICC officials, academics, and civil society leaders. By creating forums for meaningful and continual dialogue on both practical and policy issues to occur between the ICC and various American circles, the Project will establish understanding and trust between the U.S. and the ICC. Additionally, the initiatives put forth by the ICC Project will advance the noble mandate of the ICC to fortify the international rule of law. To accomplish the mission of the ICC Project, Mr. Greco highlighted the ABA's developing relationships with the primary organs of the Court, especially Madam Registrar, Silvana Arbia, a strong early supporter of the ICC Project.

It is an understatement to say that the U.S.-ICC relationship is a topic that those engaged in the field of international relations and law discuss with great interest. The U.S.-ICC relationship started positively with the U.S. playing a pivotal role in the Rome Statute negotiations. A false start on ratification under the Clinton Administration gave way to open hostility during the early years of the Bush Administration. The later years of that administration saw positive developments in the relationship, which the Obama Administration has added onto in measured fashion. This track record puts the U.S. in an odd position, because few, if any, countries are as important to international accountability for mass atrocities. From post World War II courts to modern day tribunals for the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Cambodia, the U.S. has played a central role in developing the field of international criminal justice. Yet, the U.S. is not a part of the ICC, the preeminent achievement in the field.

There are numerous arguments for and against the U.S. ratifying the Rome Statute. There are many predictions when the U.S. will join the ICC, if ever. Plus, there are those who say the U.S. not being a part of the Court in the beginning proved to be a good development, and others who say it will not be effective without the U.S. ultimately joining. Putting all of that aside for now, a sustained and meaningful national conversation in the United States must begin on whether to join the ICC or not. It is not trite to say that the millions of past, present, and future victims of international crimes demand such a conversation to occur in the world's most powerful nation.

Now, U.S. ratification of the Rome Statute is as American as it gets in my book. The greatest achievements in the American story did not come about through isolation or an unwillingness to lead multilateral efforts. World War II and the formation of the United Nations is all the evidence needed to support that claim. The American story also includes the defense of the principles of equality and fairness under the law, often times to the benefit of the historically subjugated and disenfranchised at home and abroad. The ICC embodies this exact same story, and the ICC's mission epitomizes the type of pursuit that is very much American. The ICC adheres to the most American of legal traditions and principles. However, there are those who do not agree with this assessment and there are others that have legitimate concerns about U.S. membership in the ICC. These opposing viewpoints demand education about how the Court works, and open deliberation about the ICC in the larger American audience. In short, national dialogue needs to happen for the U.S. to find out if ratification is in its best interests, and why.

In evaluating the Court's current challenges, many of which are not minor, we should not cloud over the fact that the ICC is a needed measure of justice. Taking a further step back, the ICC is just ten years old. The United States at ten years old was not even the United States, as we know it, since it was still toiling in the Articles of Confederations in 1786. Nevertheless, this is not just a reminder to be patient with the ICC. It is a reminder that a huge achievement is there for the taking. The greatest part of the American story is overcoming the biggest of odds, from the American Revolution to the Great Depression. The ICC, and the international community, faces similar odds. Ending impunity by creating a reliable international criminal enforcement system for the perpetration of the gravest crimes, and to do so in the face of the complexities of international politics and sovereignty, ranks up there in daunting tasks. Not just for America's or the ICC's interests, but for the interest of all, the U.S. must give its full support to the ICC in its fight against impunity and the establishment of the international rule of law. However, in order to get there, we first need to have a frank and informed conversation.

This article represents the views of the author and, except as specified otherwise, does not necessarily represent policy of the ABA or the ABA Center for Human Rights.