View of Harpa Reykjavik Concert Hall and Conference Centre during a storm on 2 November, 2012 - A collaboration between Henning Larsen Architects and artist Olafur Elliason that opened in 2011 - Photo: FRÉTTABLAÐIÐ/GVA Courtesy of OlafurEliasson.net

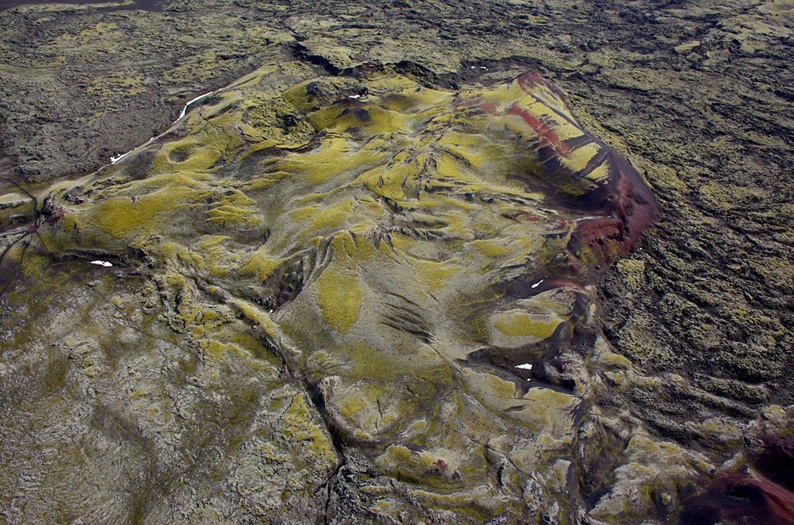

Iceland, 2012 © Olafur Eliasson Courtesy of Olafur Eliasson and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

Hurricanes, tsunamis and earthquakes battering the world's coastlines have undermined the confidence of urbanites accustomed to well-lit, static cities with streetlamps that define our comfort zones, where we take for granted ions zipping through toasters and TV, and the certainty of subways and laptops - all swiftly rendered defunct by the insouciance of gale winds.

When speaking to Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, in the days of relative calm before the storm, he recalled his encounters with arctic Iceland, which, in geological terms, is a country still in its infancy -- its ruptured, frothing lunarscape still ravaged by primordial birth pangs. Our conversation then, about the threat posed by the landscape on the unconscious, seemed uncannily relevant in post-hurricane New York.

Describing Iceland, Eliasson said, "There is that potential threat around you; the landscape is latent, difficult or dangerous, but it is hard to tell where the danger comes from." Though soft-spoken, Eliasson has a way of deliberating the tenets of his practice and methodology in very precise and thorough terms. He has always been interested in the climate's variability, and recently, in how we try to temper and harness atmospheric and geothermal energies faced with climate crises. "I'm interested in the boundaries between nature and culture, and who is negotiating that boundary," said Eliasson, "Sometimes nature has a will of its own. It has always been outside of what the culture of humankind has been able to influence. A volcano is still something non-negotiable."

The large Iceland series, From 'Volcanoes and Shelters - at Tanya Bonakdar gallery © Olafur Eliasson - Courtesy of artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

Iceland, 2012 © Olafur Eliasson - Courtesy of Olafur Eliasson and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

Back in 2010, during a stopover in Reykjavik, I was forced to yield under the violence of Eyjafjallajökull's volcanic outburst, but noticed the natives' relaxed relationship to the disruption. Elsewhere in more monolithic urbanscapes, there are things we take for granted, the ground not moving for one. "We think of reality as a rendering of something organic, interpreted through commercial, political, powerful interests," said Eliasson, "But Iceland and places like that are in flux both because they are not immediately recognizable -- and not predetermined by our expectations."

Stobe lights freeze droplets allowing diachronic perception for 'Object defined by activity (then)' Courtesy of Olafur Eliasson and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, 2012

Eliasson's art attempts to measure the world around us through our physical presence, how we engage with our surrounds, and how we perceive colour, time, motion and scale. "When you are next to the volcano," Eliasson recalled, "It's not possible to see the shape of it; you have to walk around it to feel the scale." He had flown over Iceland's Highlands to document craters in areas less accessible for human habitation, but when hiking alone in these tundra lands, without any reference to scale, distant mountains appear relative to one.

If you are unfamiliar with the terrain, you wonder if it is going to take you three hours, three days or three weeks to walk to it. If you don't move, you never find out. But if you do, you find that some rocks come closer to you very fast, and some small mountains do too, but others don't. And suddenly the walking itself creates the measurement of the topography. Once that is in place, your physicality starts to take shape -- suddenly you start to contract your body with regards to time and space. When nothing is changing, you realize that you are tiny and the landscape is huge. You become the metronome.

I suggested that the Bedouins still had a way of orienting and engaging with the desert and sky, that urban dwellers had lost.

This is easily re-cultivated, it takes maybe a summer or two. But I do think we tend to underestimate our efficiency when it comes to reading our position with regards to our surroundings. The city is a recognizable landscape... I totally agree that different types of cultures living in deserts are interesting not only because they have a very distinct night vision, using starlight -- but they have a kind of video-scopic map -- seeing the land and sky as one. We tend to look at the land as the map -- and the sky is just not there.

The hot spring series, 2012 - Courtesy of Olafur Eliasson and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

Using grids, Eliasson attempts to map the phenomena of geo-thermals, volcanoes and the sheltering huts to capture the complexity of the landscape, while acknowledging the futility of such a task. "I am organizing it in a grid, like a museum drawer. But the closer you look, the more diversified and unique everything is; representing a full range of geological diversity."

Was it to create a pattern out of chaos? "No," says Eliasson, "More like a Studiolo, a Wunderkammer of volcanoes, a perfect collection. It's a utopian idea to try to categorize and control them, to systemize them, like a pseudo-scientific project."

Designed with engineer Frederik Ottesen, Eliasson's solar-powered Little Sun lamp raises awareness of the millions that live without access to electricity.

Designed with engineer Frederik Ottesen, Eliasson's solar-powered Little Sun lamp raises awareness of the millions that live without access to electricity.

Olafur Eliasson at Tate Modern, The Weather Project 2003 © Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson Waterfalls in NY, Photo Vincent Laforet-NYTimes

Eliasson is also interested in bringing direct awareness to our physicality through his art, and his work is often an immersing experience -- waterfalls in New York's East River, a gigantic faux sun at London's Tate Modern, under which museumgoers sunbathed. "In my [weather] project at the Tate's Turbine hall -- sharing became key."

Ironically, in the power-cut after the storm, I relied on Eliasson's solar powered "Little Sun," a functional artwork he created that sells in developing countries. The aftermath of the hurricane too, was a social experiment that enforced sharing and community. Eliasson is interested in the shared experiences people have when united by an event, and how memories of events are stored differently. "We have memories of reading something horrible in the papers, and then we have a memory of having been at a similar event -- say you helped someone out of a car accident -- the two types of memories maybe about the same story but the storage of the memory is very different; one I think supports an empathic mechanic [and] has a degree of compassion."

"To know that someone else had a related experience amplifies the qualities of your own experience. That is very important if you look into social media and how social systems are developing in the internet, the friends phenomena - all these things - I'm curious about how one feels connected in the world - of course sharing an experience is one way of being connected, but I do find it slightly problematic that artists are so overly obsessed with being alone."

Tate Blackouts at Tate Modern 2012 - Lights out after 10pm and museumgoers view art with the Little Sun, bringing back a sense of mischief and wonder.© Olafur Eliasson

Tate Blackouts at Tate Modern 2012 - Lights out after 10pm and museumgoers view art with the Little Sun, bringing back a sense of mischief and wonder.© Olafur Eliasson

Eliasson feels that art history is sometimes written as if one is always alone with the world of art. "I do think collective seeing makes for a different perception. Being alone is great, and probably what I would prefer, but truth is, when you go to MoMA you are never alone -- somehow, if you read a book about MoMA, it is written as if you were alone. Some of my works can expose the social contracts that you have in place on how you behave and talk, and what your body language is. What is the social agenda in museums besides looking at art? Are they inclusive or exclusive, socially speaking, are they supportive, or counter-productive, is there a conflict of interest?"

The museum space is often defined as a singular private experience, which it rarely is -- and Eliasson asks, what if Broadway, with all its shop windows, were considered a private experience? In a reversal of the shopper as voyeur, Eliasson created art for Louis Vuitton shop windows [Eye see you, 2006], "When it comes to the street, what resources does the public sector support when defining public space, and what is the law and legislation?" asks Eliasson. "What are the values of our times when defining a park or a pedestrian path or Broadway?"

Eliasson's questions strike us especially now, as our values change - how will the city adapt to new climates, how do the synapses forming our virtual worlds bridge and map our real communities...Eliasson frames these questions with his art, lifting the curtain to make us look again.

Olafur Eliasson in front of 'The large Iceland series, 2012' Photo Kiša Lala

For more Information:

Olafur Eliasson - Volcanoes and Shelters is on view until Dec. 22, 2012 at

Tanya Bonakdar gallery New York

Text & Interviews: Kiša Lala Website

Huffingtonpost.com/kisa-lala