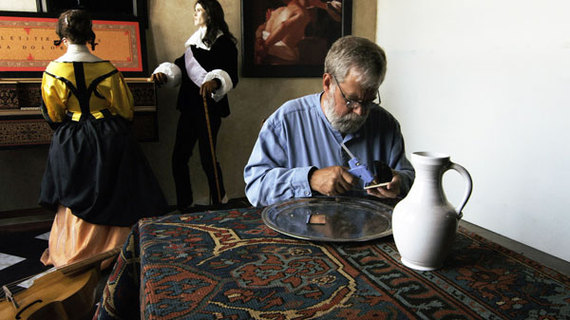

Tim Jenison assembles one of the experimental optical devices he built. Photo by Shane F. Kelly, © 2013 High Delft Pictures LLC, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.

Born in Delft in 1632, Johannes Vermeer was not a prolific painter; scholars can only definitively attribute roughly 35 paintings to him. (A few more are in dispute.) Modestly successful in his lifetime, then relatively forgotten, Vermeer was rediscovered in the 19th Century. He has since become regarded as a grand master, best known for his impeccable rendering of light and color.

In recent decades, scholars and artists have speculated about Vermeer's potential use of optics in his painting process. In his controversial book Vermeer's Camera (2001), art historian Philip Steadman explored the case for and against Vermeer's use of a camera obscura, an optical device that reflects light to project the image of objects onto a screen, rendering them in vividly sharp detail. British artist David Hockney also ignited debate with his book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters (2001), using the works themselves in an attempt to prove that optics have been used by artists for centuries.

Enter Tim Jenison, a digital video visionary who founded NewTek in 1985, leading the way for the development of desktop video production tools DigiView, DigiPaint, and the Video Toaster®. Admittedly not much of a traditional art fan, he read both Hockney and Steadman's books, and his inventor brain couldn't shake the questions that remained: did Vermeer use secret tools to achieve his photographic-like paintings? If he did, what did that painstaking process look like? And was Vermeer "cheating"?

Jenison wasn't sure Steadman and Hockney had taken things far enough, so he began to experiment. Having never painted before, he managed a striking facsimile of a black-and-white photograph of his father-in-law using a jerry-rigged mirror device of his own creation to exactly replicate light and color.

His next move was considerably grander: he recreated (to scale) Vermeer's studio, as depicted in The Music Lesson, and then set about painting a replica. That entire process is chronicled in Tim's Vermeer, a documentary that has been shortlisted for the 2014 Oscar® for Best Documentary Feature.

A Penn & Teller production, the cheeky and fascinating film features Hockney, Steadman, comedian-artist Martin Mull and producer Penn Jillette (his partner Teller directed). Jenison spoke recently about the inspiration, curiosity and tenacity behind the film.

Tim Jenison (right) demonstrates his first painting experiment to his friend, producer Penn Jillette (right). Photo by Shane F. Kelly, © 2013 High Delft Pictures LLC, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.

Kristin McCracken: Vermeer's work strikes viewers as photographic with his impeccable use of light. Have you always been a fan? What made you curious about his process?

Tim Jenison: I was about as interested in art as the next guy, which is to say, not all that much. I think I took a class in high school, I sometimes go to museums, but I'm not a fanatic. But I got David Hockney's book for Christmas one year and then I bought Steadman's book. Flipping through the pages of Steadman's book, I noticed something -- it jumped right out at me. Steadman had these two pictures side by side; one was The Music Lesson, and the other was this little dollhouse-scale model that he made of the room. He was attempting to prove that the geometry implied that lenses were used, and that the shapes and sizes of all these things were too accurate, he found, [to be painted from] eyeballing. But what jumped out at me was that the actual shades of light in the image matched exactly the model of the painting. And I go, "That's impossible."

I happen to know this because I'm a video guy, and I understand the limitations of human vision. This is a tough argument—most people think they can see pretty well—but when I saw that, I thought, "Vermeer must have used something to get those colors right. You just can't see that; you can't paint it."

KMc: Before this project, you had never really painted before. But did you consider yourself an artist? Or were you an inventor?

TJ: Most people kind of think that computer stuff -- writing software or designing electronic stuff -- is kind of the opposite of art. I never looked at it that way; I thought of writing software as a very creative process, a process of continuing invention. Most people don't think of it that way -- they think of it as homework, or math -- but that's really not what's going on there.

KMc: Yeah, it's more that your tools are different, right?

TJ: Exactly. Penn makes this point at the end of the film: "Is Tim an inventor or is Tim an artist? The problem is: we make that distinction."

KMc: How did Penn and Teller get involved? Did you have any idea the process would take so long to complete?

TJ: I'd done the first simple experiment: painting this high school photograph of my father-in-law. And then I sat down one night to have dinner with Penn Jillette -- we've been friends for 25 years or so -- in February of 2009. I told him [about my plans], and I said I was going to write a paper about it, or maybe make a YouTube video, and Penn said, "That's a really stupid idea." [Jenison laughs.] "It sounds like a good film. Teller can direct, so let's get him."

I went over to Teller's house, pitching it and explaining my idea. Both of Teller's parents were painters, so he knows a lot about art. (Penn and Teller are some of the smartest people in show business.) We got right to work, and we only finished the movie a few months ago -- the film first showed at Telluride at the end of August. We thought it was going to take about a year, so um yeah, we grossly underestimated.

KMc: Vermeer is an elusive figure. He doesn't have that many paintings on record, and he didn't find much respect until centuries after his death. Did you know much about him?

TJ: I remember seeing some of his pictures in The Louvre many, many years ago, and I thought they were nice pictures. But no, it was only when I got into this project that I jumped in with both feet. And now I know pretty much everything there is to know about Vermeer.

KMc: Which isn't much, right?

TJ: It isn't much at all. John Michael Montias has written the definitive book about Vermeer, called Vermeer and His Milieu. He went to Holland and dug up everything he could find, and he didn't find out much about Vermeer, but he found out a lot about his family. Vermeer's grandmother was a con artist -- she would put on these lotteries, and somehow no one would win. And then his grandfather on the other side of the family was a counterfeiter. So... [we know] a lot about his family, but we will never really know much more about him than we do now. He was not famous, and he was forgotten, mostly because he painted so few paintings and they went to patrons right there in Delft. They never really traveled outside Delft and its surroundings, so when Vermeer died, it was kind of the end of the story.

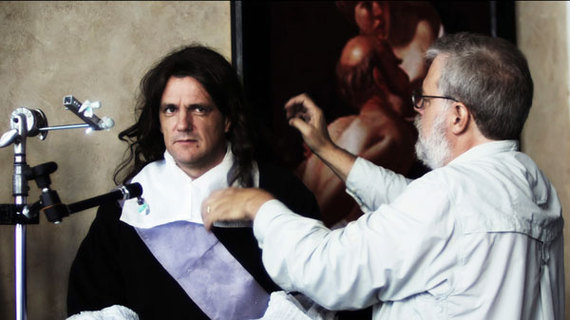

Tim Jenison (right) adjusts the wig on Graham Toms (left) who modeled as the gentleman for Tim's painting. Photo by Shane F. Kelly, © 2013 High Delft Pictures LLC, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.

KMc: If Vermeer did employ the techniques you discover and test in the film, do you consider it "cheating"? Does it make him any less of a talent?

TJ: Well, obviously it changes our perception of how he [painted], but it certainly doesn't make it any easier. In modern times, artists are just supposed to be conceptual: they are supposed to have an inspiration, and then pick up their brush and go with it. This is a very different process; everything is premeditated.

Arguably, Vermeer was just trying to make the ultimate paintings, and he would probably not have seen anything wrong with using whatever tool he could find. Now, there is the fact that he did it in secret. Does that mean he was ashamed of it, or trying to hide it? I don't think so. (Although modern artists certainly have, such as Thomas Eakins, who painted from photographs and tried to hide it.)

Artists [in Vermeer's day] kept secrets. They were members of The Guild of St. Luke, and they were kind of like the Freemasons, who would never show the laymen how to lay bricks -- that was a trade secret. So there was a culture of secrecy around the various crafts.

KMc: It took you 130 days to paint your version of The Music Lesson. Do you think it would have taken Vermeer as long to paint his paintings, if he had used this technique?

TJ: Yeah, and that was actual days of painting, so on the calendar it was longer than that. When you think about how many pictures Vermeer painted -- he painted 40 pictures in about 20 years. That's about six months per painting.

KMc: And how long does it take to paint the same size painting if one is working freehand?

TJ: Well, Rembrandt -- who was a contemporary of Vermeer's, in Amsterdam instead of Delft -- turned out well over 1000 works in his career. So yes, Vermeer's method would have been very, very slow.

KMc: Do you have a favorite Vermeer? Is it still The Music Lesson?

TJ: Yeah, it's my favorite. But I chose it for scientific reasons, because there were so many things in the room that would allow... that I could construct a model from. I could have the same lighting, and the same objects. So that harpsichord you see, that's a well-known harpsichord -- they were mass-produced by a Flemish company called Ruckers. They still exist in museums, with the same decorations on them. The viola de gamba, they were really standard. The Turkish rug, we were able to find something very similar to it...

Tim Jenison discovers a mistake in Vermeer's original painting of "The Music Lesson." Photo by Shane F. Kelly, © 2013 High Delft Pictures LLC, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics. All Rights Reserved.

KMc: How long did it take to find the rug? Because that pattern is really specific, no?

TJ: Yeah, that's a whole other sidebar. (There are so many sidebars that could have been in the film, but they ended up on the cutting room floor.) Farley Ziegler, a producer on the film, took it upon her to find the rug. She found the author of a book called Carpets in Netherlandish Paintings. [laughs]

KMc: That's a niche, huh? [laughs]

TJ: And he's an attorney in Amsterdam! She talked to him, and he referred us to an expert in the U.S., named Denny. Denny knew exactly what the carpet was, and he said, "I have never seen a carpet just like this. I know of some that are kind of similar; maybe we could arrange to borrow one from the owners." Then he called one day and said, "You won't believe this, but there's a rug on sale at Christie's that is a dead ringer for Vermeer's rug; I've never seen anything closer." He thought it would go cheap, because it was too big to hang on the wall, and too good to put on the floor. And so, yeah, it did go for the minimum, so we were able to get it for eight grand.

KMc: And do you own it still?

TJ: Yes, It's still in the room—the room is still set up. If you're ever in San Antonio, stop by.

KMc: What's next? Do you have something else that is burning a hole in your mind?

TJ: Always. In the art field, I'd like to follow this thread -- I won't make another movie -- but I'd like to keep following this thread, which seems to me to go back to Leonardo's time...

Tim's Vermeer is now playing at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas in NY for one week. It will open in select cities on January 31, 2014.

Four Vermeers—three in the permanent collection, and one (the iconic 'Girl With a Pearl Earring') in a visiting exhibit -- are currently on display at The Frick Collection in New York City.