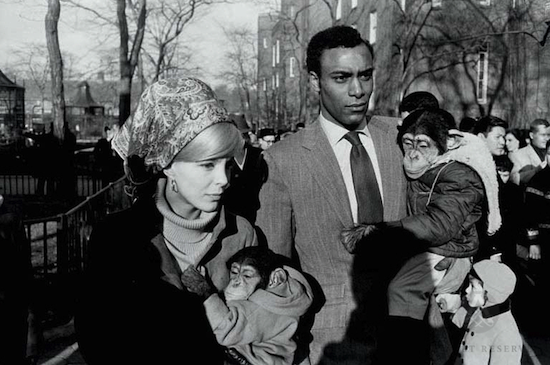

Garry Winogrand, Metropolitan Opera, New York, ca. 1951; posthumous digital reproduction from original negative; Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

The first several hours I spent in SFMOMA's Garry Winogrand retrospective, I thought writing about it would be easy: it seemed like each of the 300 images offered such imaginative fodder that the only problem would be to avoid long-windedness. But eventually I realized that that approach would be pointless, for the very reason that Winogrand's work, while never simple or obvious, isn't exactly opaque, either. They're not the sort of images that one blinks at for a while before concluding that art is incomprehensible and wandering off in a state of alienation. The confluence of aesthetic and dramatic elements in each image is incredibly engaging -- however one interprets them. What is the black man thinking as he stares into the eyes of the dehorned rhino in "Bronx Zoo, New York," made in the turbulent year of 1963? What is the rhino thinking, for that matter? What is the tuxedoed man shouting as he drives his slick car in 1959's "New York"? Or is he singing along with the radio? Is there someone just out of sight in the passenger seat that he's shouting at or is he just taking advantage of a moment to himself in his car to enjoy a good scream? Is it reading too much into the image of the suited man of late middle-age from 1960, to think that the angle at which his solid frame is set against that of the tall buildings around him, and the gesture of pulling his spectacles case out of his inside breast pocket (or replacing it?), together with the grimace on his face, combine to look nearly like the posture of a man clutching at his chest at the start of a heart attack? And that the seeming grimness of his solitary experience is amplified by the comparatively jolly, oblivious men chatting behind him?

Part of what's delightful about the collection is deciphering these elements as if they were clues to a hidden storyline, and then marveling at the fact that there is no storyline; that these are just rich, spontaneous momentary scenes that Winogrand managed to recognize and capture in the moment of convergence. Taken together, one could posit that they create a storyline of sorts of the American middle-century. To that end, the exhibition is divided into three parts: "Down from the Bronx" concentrates on photographs he took in New York between 1950 and 1971, "A Student of America," on photographs from the same decades taken during trips outside New York, and "Boom and Bust," also outside New York, from 1971 to his death in 1984. The common line on Winogrand's canon is that the darkening of his vision over the decades reflected the country's growing disenchantment in the post-Nixon years. This is not quite persuasive as an explication of Winogrand's practice, nor of his vast, mercurial subject. One might, for instance, object to the presumption that everyone should share the same view of America, that there was, in fact, this downward turn of mood starting in the '70s. Well, yes, maybe for some people, but if you were black, or a feminist, or homosexual, or pro-choice, or anti-HUAC, you might have felt the opposite, and that it was rather the entrenched and legislated bigotries of the '50's that had been disenchanting.

Garry Winogrand, Central Park Zoo, New York, 1967; gelatin silver print; Collection of Randi and Bob Fisher; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

This interpretation also disregards the presence of more troubling material in the New York years. But such examples, though rare, are stunning. In one image from 1960, a woman makes her way through the cold and driven snow down what looks to be one of the wide, brownstone-lined streets of Harlem. She is black and she appears to be poor: rather than a shawl, she's wrapped around her head a neckscarf, which isn't wide enough to cover the back of her head or neck, or even long enough to tie under her chin, so she's fastened it with a safety pin. For an era when a certain fastidiousness with one's toilette was customary, regardless of a person's means, she seems strangely unkempt. Her scarf is sloppily hung, and her coat is missing a button. These bits of negligence echo a dejection in her face. She seems tired, sad, and is one of the few women Winogrand photographs at such proximity who does not even look up at him (notable because this was also an era before the ubiquity -- and compactness -- of cameras; surely she would have noticed the tall ginger with his lens trained on her?).

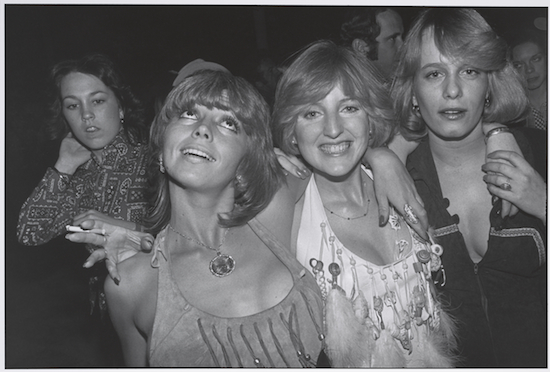

The opposite is also true for the later work. Who could fail to detect some humor in such images as 1975's "Fort Worth," in which a boy's smooth round face and tiny eyes weirdly resemble that of the sheep standing next to him? Or in the likeness of smiles on the faces of the elephants drinking from their waterbucket in 1974's "Austin"? Is the tipsy ebullience of the three ladies in (another) "Fort Worth" from 1974-77 any less authentic than that of the slightly more polished but still frisky couple at the Metropolitan Opera in 1951 (top image)?

Garry Winogrand, Fort Worth, Texas, 1974-77. Gelatin silver print. Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Neither is it clear that the pall Winogrand's work took on over the years (if we concede that it did) says more about the country he tasked himself with describing than it does about him. It's not so out-of-the-ordinary for an artist as he ages to pass through an idealism or at least an exuberant realism (which is how I'd describe Winogrand's New York work) into a more somber realism, or even unabashed expressionism, regardless of time or place. The young Donatello sculpted jaunty young Davids in gleaming marble and shining bronze, but towards the end of his life carved a harrowed, harrowing, Magdalene Penitent out of poplar wood. Goya went from rather sassy royal portraits and The Naked Maja to nightmares like Saturn Devouring his Son and the Black Paintings. Winogrand had much less time to experience and document the disintegration of his Weltanschauung, dying young and suddenly at age 56. Nevertheless if his work changes in tone over the arc of his truncated career, it might be worth considering a less neat (and historically-selective) explanation than that "America went to s***, obviously, and so did his photographs."

One thing I found fascinating was what Winogrand himself said about his work in his second Guggenheim Fellowship application.

I look at the pictures I have done up to now, and they make me feel that who we are and how we feel and what is to become of us just doesn't matter. Our aspirations and successes have been cheap and petty. I read the newspapers, the columnists, some books, I look at some magazines (our press). They all deal in illusions and fantasies. I can only conclude that we have lost ourselves, and that the bomb may finish the job permanently, and it just doesn't matter, we have not loved life.

This was in 1964, in the midst of what many consider the brighter period of his career. One has to be careful when considering an artist's stated opinions of his subject. An artist's creation will speak to people in ways that he no longer controls, and if it says something he meant it not to, or doesn't say something he hoped it would, that's too bad for him. Indeed, it is hard to adopt Winogrand's cynicism when looking over the images in "Down from the Bronx"; in fact, it almost hurts to do so. They convey so many moods, express such a multitude of recognizable nuances of experience, one wants to think that what one sees in them is not just the American-, but the human experience. One can walk through the exhibition halls (or leaf through the catalogue*), regarding not only "Down from the Bronx" but the other two divisions of his works as well, and think, "I have been these people. I have been this exhausted, melancholy woman slumped over in my bus seat, staring unseeing out the window. I have been this child playing with the heavy glass doors of some grown-up place my parents brought me to, because anyplace can be fun if you treat it like a playground. I have been this woman, wearing a little too much makeup, laughing a little too loudly, trying a little too hard to engage the affections of clearly distracted man. Hell, I've been this bear, on undignified display at the zoo, trying to chomp through his name sign -- how dare anyone presume to define me!" It's hard not to take Winogrand's dismissal of the life he captured through his lens personally; it feels like a dismissal of the self -- not of one's Americanism but of one's humanity.

Garry Winogrand, Los Angeles, 1980-83; posthumous digital reproduction from original negative; Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

One doesn't have to review Winogrand's work with his jaundiced assessment of the subject in mind. But doing so might connect his early- to his later work in a way that doesn't depend on a very limited reading of American history in those decades.

Winogrand took thousands upon thousands of photographs in his career. He didn't even bother printing most of them**. He didn't hire models or choreograph situations; with formidable energy and tenacity he photographed the world as it was playing out before him, pursuing scenes wherein he thought he might learn, and reveal, the American experience. What does it mean when a street photographer believes the scenes he's captured on film to reveal such pettiness and fakery as he bemoaned in 1964? Isn't authenticity the essence of street photography? And isn't its nature to reveal some aspect of truth, however small? One would think that the non-manipulative nature of street photography would reveal whatever is genuine, even in a "lost" people, and perhaps even be the only thing that could do that. Do the less theatrical images Winogrand took in the following two decades represent him digging, if not deeper, then differently, to find some germ of that authenticity he had felt was cheapened and crowded out by the "illusions and fantasies" of the previous years? Or is their somberness a result of his having given up on finding that authenticity, and pursuing, with ever-blackening mood, scenes that reflected his own nihilism?

What started out as an exhibition of work that practically shouted to me answers to questions I hadn't thought to ask, later led me into a confusion I had not anticipated, and now I'm left muttering a slew of unanswerable questions to myself, about America, about photography, about how active a viewer I have to be to get the richest reading of seemingly-straightforward work. I'm wondering if even street photography can be trusted to tell us anything beyond what is in the photographer's own heart at the moment--I wonder if it is in fact the most deceptive of all genres, for the very reason that it posits a certain objectivity, not rehearsed and posed but candid and full of accidents, an imprint of a reality that is out there for anyone and everyone to witness together. I wonder if, regardless of the literal elements of the scene, the tone an image takes on and expresses is due to the photographer's own moods, his own prejudices, enthusiasms, "abortive sorrows and short-winded elations." And then I wonder if this is in fact any less reliable than the notion that the images can say something objectively true about their over-arching subject (for instance, America) when that subject is itself so complex, many-sided, and open to a seemingly endless range of interpretations.

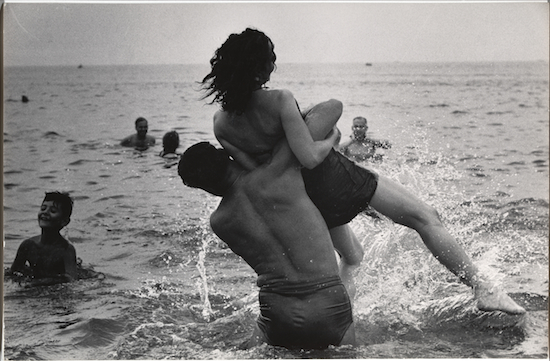

Garry Winogrand, Coney Island, New York, ca. 1952; gelatin silver print; collection The Museum of Modern Art, New York, purchase and gift of Barbara Schwartz in memory of Eugene M. Schwartz; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/ Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Footnotes:

*The catalogue itself is massive and well worth purchasing. As well as excellent essays by curators Erin O'Toole, Sandra Phillips, Sarah Greenough, Tod Papageorge, and Winogrand's friend and mentee Leo Rubenfein, it features even more images than are present in the show. However, some of the lay-out choices are perplexing. All of the photographs, regardless of size and shape, are placed less than half-an inch from the gutter. While this makes sense for the longer, horizontal, rectangular images, that stretch nearly all the way to the outside edge of the page, it makes less sense for the narrower ones, and even less for the verticals. Many of them have outside margins of nearly two and a half inches. That's less than half an inch on the gutter, two and a half inches on the outside. Did the designers think we'd be writing notes in the margins? I'm not a book designer and am not particularly interested in design elements that don't specifically facilitate legibility, both for text and images. So I can't see why, rather than place those images more centrally on the page, or even closer to the outside margin, where we could almost lay the page flat and examine the images easily, they've placed them so close to the gutter that the inside edge of the picture gets almost lost to the curve and shadow of the gutter, especially towards the middle of the (463 page) book, where the crest of the pages is at its greatest. One photograph of a blonde woman in a shift dress ("New York 1965") is a vertical shot. There are nearly four inches on the outside edge of this photograph, with the standard less-than-half-inch on the inside, causing the image to visually elide with the one on the opposite page, a broad horizontal shot of a laughing woman ("New York, 1968"). If I'm interested in Winogrand's art, then I don't want to have to fight the gutter or some arbitrary trompe l'oeil imposed by a book designer, or any other such visual complications in order to examine and enjoy it.

**In fact, a large number of the displayed photographs were posthumously printed and curated from those thousands specifically for this exhibition, which invites the question, "Where does a photographer's work begin and end?" Winogrand was only really interested in the shooting, but may photographers are just as finicky about printing as about shooting. If the photographer had no part in the choosing of his displayable works, and in fact never even saw them except in the moment of releasing the shutter, is he less of an artist than one who controls the "life" of an image from that moment through to printing, editing, framing, hanging, and installation? Photography is one of the very few art forms we can ask these questions about. One can't root around in a dead poet's brain and find poems he never wrote out, or find dances that a dancer never himself physicalized. A painter has a much more aggressive engagement with the sketches he makes prior to painting the final scene than does a photographer who doesn't develop his film after use; after all, even if a painter threw out his sketches and never used them for a final painting, those sketches represent his deliberate process enacted in the medium he worked in. An undeveloped role of film represents something the photographer saw, and considered worth capturing, but never worked on or even looked at in the medium of his practice, i.e. on photographic paper (or in a tif or jpeg, I suppose). That means that for a large number of images we see in this exhibition, Winogrand, ever-prepared and attuned, had seen and snapped live, moving scenes in color, but never bothered with the scenes thereafter, never seeing what they looked like on paper or how the compositions turned out or chose this one over that one or considered what they looked like in black and white. And what we see are black-and-white still images examined, evaluated, culled from thousands, and printed by people who are not Winogrand. But these works are considered Winogrand's art. That could mean something or nothing.

This retrospective will be at SFMOMA through June 2nd, and then travel to Washington, D.C.'s National Gallery of Art.

Garry Winogrand, Fort Worth, Texas, 1975; gelatin silver print; Collection SFMOMA, gift of Dr. Paul Getz; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco