Denise and I missed the Dawn Ceremony at the Shrine of Remembrance on ANZAC Day 2016. We needed to be up by 4:30 am and out of the house by 5:15 am because we intended to walk the 2.6 kilometres from Hardy Street in South Yarra to the Shrine. It takes about 30 minutes to get there. The Ceremony was to begin at 5:45 am and end at dawn about 45 minutes.

But we missed the Ceremony and the subsequent parade of the descendants of those who fought in the Great War along with living veterans and their families of subsequent wars in which the troops of Australia and New Zealand participated. Unfortunately, Passover weekend coincided with ANZAC Day. We didn't get home from the Seder we attended until 1:30 am, early Monday morning. It is said many younger Australians hit the bars and taverns of Melbourne the night before the Ceremony and simply stay up through the night. I don't know about Denise, but I speak for myself when I say I lost that kind of stamina decades ago.

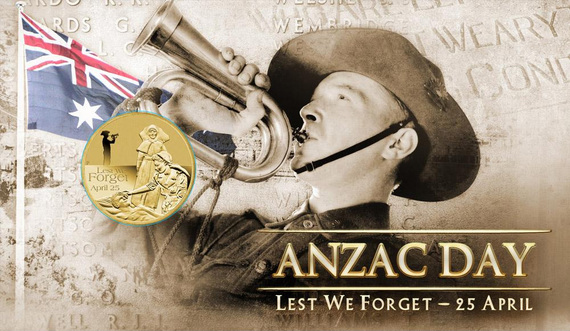

But I am very sorry I missed the event for I've heard that one cannot really understand the Australian character without participating in an ANZAC Day event. ANZAC stands for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corp. The ANZAC troops constituted a major part of the Western Allies that landed at Gallipoli, a peninsula on the Black Sea on April 25, 1915 in an operation as part of World War I (or "The Great War"). Many feel that the strategy to attack Ottoman Turkey (an ally of Germany in the First World War) was ill conceived. Indeed, the ANZACs were stuck on the beachhead for seven months before they were withdrawn.

Tactically then, Gallipoli was a defeat. But more importantly, the battle signaled the beginning of horrific casualties and losses on both sides of the World War I conflict. The deaths suffered as a result of the Gallipoli campaign were as follows: Australians 8709, New Zealanders 2701, British 21,255 and Turks 86,692. By September 1915, monuments were already being erected in Australia to commemorate the battle. The first ANZAC Commemoration Day was held on April 25, 1916 and has been an annual event in Australia, New Zealand and a host of other countries since then.

To understand the impact of the Great War on Australia and New Zealand one must appreciate the overall impact it had physically and psychically on these two nations. Overall there were 214,000 Aussie casualties with around 60,000 dead by the end of the war. Approximately one of three Australian men between the ages of 18 and 45 were either wounded or killed. Among Kiwis, 58,000 were killed or wounded. The overall New Zealand population of one million was reduced by 1.6%.

More Australians were killed in World War I than in World War II (27,073 killed or missing in the Second World War). Comparisons can be made only to the number of Americans killed in the Civil War (more casualties than in all the other wars America fought combined) or to the losses suffered by the Soviet Union and Germany during World War II. But there is much, much more attached to Gallipoli and Australia's participation in the Great War than just the deaths -- making its appreciation critical to understanding the Australian mythic character. Mind you, the following is an attempt by a American living in Melbourne for only eleven months who will try to take a crack at interpreting one hundred year old actions that Australians themselves have worked on explaining continuously since.

Australia had only been an independent nation for fourteen years and was still a nation filled with ex-Britons in 1914. There was a sense of local threat from recent German incursions into South East Asia. Indeed, the first actions Australia took in World War I were to easily overpower German resistance in Nauru, the Caroline Islands and German New Guinea. Yes, that's the same Nauru that now is the infamous way station/detention camp for illegal aliens caught attempting to enter Australia proper. Australia wanted to prove itself as a nation and within the vestigial 19th century ideas of manhood (and nationhood) the best way was to participate in (and win) a war. Theodore Roosevelt (and much of the U.S.) was held sway under similar influences with his Rough Rider stint and America's participation in the Spanish-American War of 1898.

So there was no need for conscription in Oz when the guns of August erupted in 1914 in Europe. I believe Australia's convict historical origins were an additional factor leading the nation to want to show its mettle and value to the mother country and the world. The sense of British betrayal at Gallipoli and even more so on the battlefields of Fromelles and Pozieres in France (where more Australians died than at Gallipoli) was acute and long lasting. Indeed, my only previous exposure to the Australian experience of the Great War had been through Gallipoli the 1981 tragic film by the Australian director, Peter Weir. In it an idealistic Aussie hero/protagonist, a young Mel Gibson, dies at the film's close as a consequence of unfeeling and incompetent British leadership.

The Allies did win the war, ironically aided by the great military leadership of the relatively unsung, Australian general, George Monash - who was also Jewish, by the way. A Melbourne native, he does have an important local freeway and university named after him here. But the Australians had to make sense of their willing participation in the slaughter of so many young men. Hence the ANZAC Day rituals that have honored the sacrifice of the mythic tough, independent Australian bushman devoted to his regiment, his squadron and brigade; what Damian Hall (Principal, Janet Clarke Hall; Senior Fellow, School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, The University of Melbourne) refers to as the quintessence of that particular Australian notion of "mateship."

British-Australian cooperation (or lack of it) during World War II did little to improve trust between Oz and Whitehall. In fact, Australians during the Second World War moved ever closer militarily to the United States, with whom they have fought in every war that America has launched since. Finally, only in the 1990s with the beginning of Australia's still continuing economic boom, do I believe this sense of national inferiority began to wane and perhaps disappear. Aussies are realistic that they are still a relatively small country compared to the U.S. or China. But Australia operates much more independently these days, based upon a growing national self-belief and a clear memory of being exploited in the past.

ANZAC Day means many different things to Australians, young and old, native born and immigrant. In Melbourne this morning some 45,000 people awoke before dawn and attended the 5:45 am ceremony at the Shrine of Remembrance. While the numbers were down from last year's record for the centenary of Gallipoli ANZAC Day, I cannot not think of that many Americans getting up that early for anything - except to be first at the mall for the pre-Christmas sales on Black Friday after Thanksgiving. And that, I suppose, is yet another rather depressing comparison between these two countries' passions.

And now for our regular Australian language lesson for Americans:

•quokka - a small wallaby inhabiting islands and swampy areas in southwestern Australia (e.g. Rottnest Island off Perth). I thank one observant Australian reader of the Letter, Jason, who somehow was able to interpret my question on "quallas" a while back in a previous Letter as my poor memory for "quokkas" - he was absolutely right on. Thanks Jason.•moggy (or moggie) -- a cat (British informal)•gormless - lacking in vitality or intelligence; stupid, dull or clumsy (British informal)•aerobridge -- a jet bridge, an enclosed, movable connector which most commonly extends from an airport. Americans call this an airplane ramp.•relief or emergency teacher -- an itinerant teacher who fills in for another. Americans call this a substitute teacher. You might anticipate, the Aussies often abbreviate a relief or emergency teacher as an ET (I already feel sorry for them).

Denise and I have bought our plane tickets departing Melbourne June 6th for a hopscotch approach to our return to Oakland arriving June 22nd, via Perth, Singapore, Shanghai and Honolulu. The fate of the Letter from Melbourne continuing much beyond June would seem problematic. Perhaps a Letter from California might try to look at the challenges of reentering the American scene after a year in the land of Oz. We'll see. Until then..