Two weeks ago, on the morning of March 18, I was in Haiti to witness the return of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Haiti's twice democratically elected, former president, who was coming home after seven years in exile in South Africa. I waited in the courtyard of his home in Tabarre, along with friends and supporters mostly Haitian, a few foreigners like myself who had come to celebrate. When word came that the plane had landed, a hush fell among us.

Two weeks ago, on the morning of March 18, I was in Haiti to witness the return of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Haiti's twice democratically elected, former president, who was coming home after seven years in exile in South Africa. I waited in the courtyard of his home in Tabarre, along with friends and supporters mostly Haitian, a few foreigners like myself who had come to celebrate. When word came that the plane had landed, a hush fell among us.

Twenty minutes or so later, Aristide's voice came over the radio; the country fell silent. I leaned into the open window of friend's car to listen. In Les Cayes, and Cap Haitian, in Gonaives, and Petit Goaves, in Jeremie people who'd gathered in the streets to celebrate the return stopped and held up their radios. Tout moun Fremi, said my friend Jorge later, shaking with emotion as they heard Aristide's voice come over the radio from Haitian soil for the first time in seven years. Haitian TV later showed scenes of young people, market women, people in tent camps, crying as they listened.

"My sisters and brothers," Aristide said, "you would have to put your hand on my heart to feel how fast and strongly it is beating right now."

In fact, the emotion was clear in his voice, the relief, the joy, the warmth, as he sent greetings out to his people. The country breathed a collective sigh of relief; the weight of a seven-year stone lifted. The plane had landed safely, Aristide was on Haitian soil, and he had not changed. "When you hear Aristide's voice on the radio," someone once told me, "it is like he's pouring honey in your ear."

After the earthquake, after the cholera, after the November 28th elections, which made a mockery of democracy, after the unimaginable suffering the Haitian people have endured this last most terrible year of Haitian history, a little honey in the ear was desperately needed.

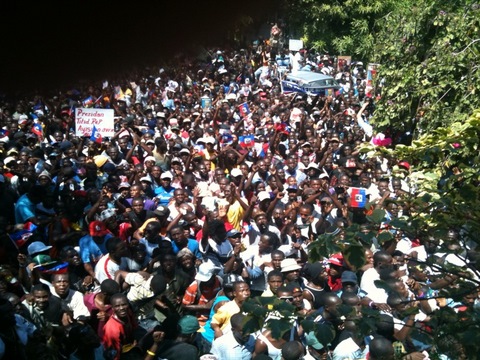

"Since the earthquake," Aristide said, "Since the goudougoudou (an onomatopoeic Creole term for the earthquake), I've felt that if I could, I would transform the chambers of my heart into the chambers of a house, where each victim would find a home and no longer have to sleep in the streets, in the mud, under these torn and tattered, scraps of plastic, sheets, or cardboard of humiliation." When the speech ended, the car carrying President Aristide and his family left the airport amid a crush of gathering crowds who filled the roads, mobbed the car, slowed the motorcade to a crawl. At a construction site in Port-au-Prince workers were filmed throwing down their tools and running in the direction of the airport to see with their own eyes.

Standing on the steps of Aristide's house as we waited -- it took over an hour and a half for Aristide's car to make the two-mile of so trip from the airport to his home -- I spoke with Venel Ramarais, one of Haiti's most distinguished journalists. In the late 70's and early 80's Ramarais was the director of Radio Soleil, the church radio station that was a leading voice in the movement to overthrow of the thirty-year Duvalier regime. Ramarais confessed that over the past seven years, since the coup and kidnapping, there had been times when he'd doubted if a lifetime dedicated to the struggle for democracy and freedom of speech had been worth it. The lowest point had come in January, when an already broken country had been subjected to the return of former dictator, Jean-Claude Duvalier. To all those who participated in the movement to overthrow Duvalier and the birth of democracy in Haiti, Duvalier's return was a kick in the teeth. The final blow. As if to say: you are nothing, Haiti is worse off now then when you began. Your movement, your labor, your life amounts to nothing. Which was perhaps the point, the intended impact of whoever engineered or allowed Duvalier's return.

Since January I'd had similar conversations with several other lifelong activists, leaders of the Lavalas movement. For each of them Duvalier's return raised the same question: could they really go on with the struggle?

A few days after Duvalier's return, I also spoke with Aristide by phone in South Africa. I feared he too would be devastated. But his voice was light, perhaps because he saw immediately that Duvalier, sick and bumbling in Haiti most likely as a pawn of others, had just unwittingly cracked open the door for his own return.

When the car finally arrived at the gates of the house we heard sirens muffled by a thunderous crowd. The gates were pulled open, and thousands of people streamed into the yard. Within minutes the whole courtyard was pounding with joy, people surrounding the car, and pressing towards the house. I found myself crushed between revelers, the relatively small security team, a few well-dressed Haitians who'd been expecting to receive the former president with a bit more formality, plus a smattering of journalists. After ten or so minutes of smashed feet, of moving with the wild undulations of the crowd, of security frantically pushing back, with everyone struggling to stay calm as they said, calm, calm, calm, to each other, someone pulled me in through the front door of the house.

Later on TV, I saw the images of hundreds of people scaling the walls around the property. Streaming over is more accurate, up a thirteen-foot wall, over a huge roll of barbwire, they went, boosting one another up, extending a hand down, while a massive, joyous crowd danced along the whole road leading to the gates. The image, shown repeatedly on Haitian television over the next few days, of all those bodies going up over the walls, right through the barb wire, must have put terror in the hearts of all Haitians who live behind walls that are not supposed to be scalable.

"Exclusion is the problem, inclusion is the solution," Aristide said from the airport, in what would become the defining refrain of the day. He referred both to the exclusion of Fanmi Lavalas, Haiti's largest political party from the elections, which were set to take place in two days, and the fundamental exclusion of the Haitian poor majority from the benefits of citizenship.

It took another thirty minutes for the security team to open up enough space for the Aristide family to emerge from the car. First came the girls, Michaelle, twelve-years-old, dashing head down through the crowd, then fourteen-year-old Christine. The girls' little white dog, Blanco, who they'd carried on the plane all the way from South Africa (and who somehow had already made it into the house), came running out to meet them.

A few minutes later Mildred Aristide appeared, half-walking, half-carried into the house, glasses askew, hair messed, dress rumpled, but looking instantly happy as she landed in the living room of the house she hadn't seen in seven years.

A while later a huge roar from the crowd, and Titid was delivered in through the door, one shoe coming off, glasses on his forehead, and his hair all mussed by the many hands that run over his head. And then laughing, as he too touched home.

The two of them looked as if their return had required all the travail of being born, as if it had taken every ounce of self and energy they possessed to get back to this home from which they had been kidnapped seven years earlier. And it had.

I was in Haiti for Aristide's return in 1994 as well. That too was a joyous day. But this return was far sweeter, far more perilous, and far more unlikely. The scale of the event in 1994 was larger because Aristide was the president returning to the palace. The time of the return was known in advance, and people could gather on the vast space of the Champs Mars to hear him speak. But that day was filled with contradiction. Aristide returned to Haiti along with 20,000 US troops, a compromise that he and most Haitians accepted in order to rid themselves of a brutal military dictatorship. But it rankled.

This time the exile was twice as long, the coup of 2004 far more devastating both in terms of loss of life and in its near success in trying to erase Aristide and Lavalas from Haitian history. A single private plane came halfway across the world, with explicit threats to its safety delivered right up until takeoff. This time, an African president gave the word that allowed the plane to leave. (And an African-American president called at the last minute to try to stop it!) It happened anyway. Without permission and without compromise, Aristide returned to Haiti a free man.

In the courtyard of Aristide's house on the day of this return, people stayed on, hoping he would emerge and speak again. (There was no sound system, and nowhere near enough security to pull that off, plus he'd said what he had to say from the airport). From the outside, the house looked like a three-tiered wedding cake, decorated at every level with people, who shimmied up the coconut trees, onto the roof, and the balconies, who ate mangoes from the mango trees, who cracked open coconuts and passed them down to the crowd below, who reveled, and smiled, and claimed the house and its occupants as their own.

No one got hurt, and no one broke into the house itself, though certainly they could have. An American friend of mine lost his wallet in the crowd, and hours later, someone he knew came running after him to say he had it, someone had given it to someone who had given it to someone else until they found him. The money was gone, but everything else was still there. A Haitian friend lost his cell phone in the melee. Later he got a call from someone who'd found it, taken it home and charged it, then called him to say come get it.

Eventually, when they'd had their sit on the roof and eaten their mangos, and peered in the windows, when it became clear Titid would not speak, the crowd slowly and peacefully dispersed.

A rather disheveled press core remained, sitting on the thoroughly trampled grass in in front of the house, still fixated on the idea that Aristide would make a statement about the elections, call for a boycott or endorse a candidate, or otherwise "destabilize" the country as the Americans had insisted he would. They begged to know when he would appear in public, where would he vote, when they could get a photo op. Photo op? How about the moment he stepped from the plane, both hands in the air? Or the crowds dancing on the road? Or the house covered with people? Alas, joy in Haiti is not newsworthy. Aristide's triumphant return garnered almost no news coverage in the mainstream media in the US.

Which does not alter one bit what Haitians experienced on March 18. As someone said to me late that day: The New York Times does not make Haitian history.

Aristide's return to Haiti changes nothing. Aristide's return changes everything.

A million or so Haitians are still without homes. The latest study now predicts over 800,000 Haitians will be infected with cholera before the disease runs its course. And eleven thousand more will die. Haiti is still occupied by a UN force, which brought cholera to the country, which consumes half a billion dollars a year, yet has not built a single school or hospital, and which is not even able to contribute adequately for the care of those it has infected. The international community, headed by the US government, has now carried out a "selection" as Haitians call the recent elections. Voter turnout for the first round was 22%, the second round turnout appeared to be even lower. A perilously weak government will emerge, one disconnected from its people, unable to mobilize or even communicate with them.

And yet, for those who were asking just two months ago if they could possibly go on struggling for change, Aristide's return is, at last, a taste of justice. For those sweltering in tents in the hot sun, this is a breath of hope. Yes, I know, people cannot eat hope. But they also cannot rebuild a country without it. And for everyone in Haiti and abroad, who worked for this return, it is proof that the US government does not control every last inch of this earth. A plane can take off from South Africa and land in Haiti without their consent. A person can scale a thirteen-foot wall and land on their feet on the other side.

Photos courtesy of Paul Burke.