[Parts 1 and 2 of "On the Future of Wagnerism" were published on Huffington Post on 2/18/14 and 4/23/14]

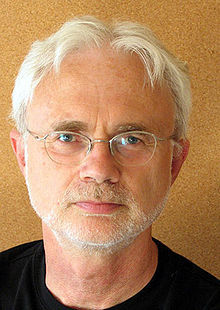

Richard Wagner

Playing out before us is the Wagner situation redux. In anticipation of the Metropolitan Opera's new production of The Death of Klinghoffer, a co-creation of composer John Adams, librettist Alice Goodman and director Peter Sellars, Jewish individuals and groups are once again expressing concerns about the perceived anti-Semitic implications and the potential to stoke anti-Semitism of the opera, which has aroused strong reactions from all sides since its world premiere in Brussels in 1991. Artistic freedom defenders and partisans of Klinghoffer are once again indignant about any proposed accommodations of those concerns as well as about the concerns themselves.

Because of my writing about the enduring toxicity of Wagner's anti-Semitism, it might be inferred that I would support the Met's decision not to broadcast Klinghoffer on its Live from the Met HD series. While I do sometimes question decisions about the status of Wagner in the repertoire and share Jewish concerns about Klinghoffer, let me be clear that I do not believe that any composer or work of art or staging should be censored or banned.

But just as I do not want or expect Wagner to be banned or censored, I do not want discussion of the ongoing fallout from the depth and seriousness of Wagner's anti-Semitism to be bullied into submission or silence. Though I support his right to say it, I don't want to be told that Wagner is "stuck in a Nazi rut," as New Yorker music critic Alex Ross observed, with the implication that any further discussion of the Wagner-Hitler connection is now officially exhausted, inappropriate and unwelcome. I do not want to be told implicitly what my life-partner Arnie Kantrowitz was told explicitly by his close boyhood friend when Arnie asked him if Wagner's art was more important than the lives of 6 million Jews: "Yes."

The same holds true for Klinghoffer and its creators. Having made the questionable, controversial decision to stage it, the Met should not now be having eleventh-hour misgivings about the broadcasting of it, even though concerns about it playing into escalating anti-Semitism in Europe and elsewhere seem justified. Consider Graham Vick's production of Moses in Egypt, a long-neglected Rossini masterpiece, for the Rossini Festival in Pesaro (Rossini's home town) in 2011, the video of which was released in 2013. In a staging that sounds more like a satire of the whole "Eurotrash" era of deconstructing opera than any truth it might touch on, Vick, an epigone of Sellars, turned the Jews into the terrorists. The Egyptians became their Palestinian victims and Moses was made to resemble Osama bin Laden. Although such a staging might not be expected to play well in New York, it garnered plenty of attention and praise during its run in Europe, receiving one of Italy's most prestigious critics' awards. In "Using Minds To Poison Opera Against Israel," Myron Kaplan draws the unavoidable conclusion in The Jewish Voice that "The production, a huge success in Europe, is meant to indoctrinate people with the idea that Israel is the villain in its conflict with the Palestinian Arabs."

So what are the issues here? In order to appreciate the problem with Klinghoffer, we have to go back to Nixon in China, an earlier co-creation of Adams, Sellars and Goodman. It has been a tenet of Goodman's work, as she herself has repeatedly tried to characterize it, to give balance and dimension to the various protagonists and cohorts, to allow them to express themselves, to give voice to their inner thoughts and feelings. Thus Mao, one of history's greatest mass-murderers (some would rank his democide as the greatest in human history), is humanized in her libretto for Nixon in China. Likewise Nixon, Pat Nixon, Chou en Lai and even Madame Mao, whose portrait is not flattering but who has the opera's most thrilling music. What Goodman says is her intention to be fair is indeed apparent almost everywhere, at least on the surface, and this is likewise true of Klinghoffer, however one might question her claim to a balanced portrayal of the plight of the Palestinians vs. the Jews and Israelis. Of course, this ostensible balance and fairness of Goodman's libretto is apart from the questions Richard Taruskin has raised in The Danger of Music and Other Anti-Utopian Essays re Adams' musical characterizations favoring the Palestinians.

Goodman's professed balance calls attention to itself at every turn, but with one very big exception: the portrayal of Henry Kissinger in Nixon in China. There isn't a moment of his role that is anything less than a vicious and gratuitous caricature. Goodman's--and with her's, Sellars' and Adams'--hostility towards this character begs for greater scrutiny than it got from our critics, although a number of them did note that Kissinger was singularly pilloried.

Reviewing the opera's landing at the Metropolitan Opera in 2011, Anthony Tommasini observed in the New York Times that "With the exception of Henry Kissinger, all the historic players in the drama are treated seriously and given a dignity that allows for plenty of humor and absurdity...I have never understood why the Kissinger character alone is turned into a caricature." In Opera and Medicine, Neil Kurtzman wrote that "The libretto by Alice Goodman treats all of the characters in the piece seriously with the exception of Henry Kissinger, whose X-rated cartoon depiction is so out of keeping with the rest of the action that it can only be considered the result of sophomoric malice." In the New York Jewish Week, Eric Herschethal wrote that '"Nixon in China' gives comfort to Kissinger's most vociferous critics...the opera portrays him as cruel, cunning and entirely devoid of human feeling." Tim Page, a Pulitzer Prize-winning critic, concluded in his original 1988 review that "to treat the president even-handedly and then to transform the secretary of state into a venal, jibbering, opportunistic buffoon is to lower the level of discourse considerably." (If Alex Ross, an ardent admirer of Nixon in China, ever commented on the opera's characterization of Kissinger, I could not locate it.)

Why was Kissinger targeted for such singular treatment, as being so much worse, so much more culpable, so much less human, than Mao, Nixon or even Madame Mao? Is it because he deserved that level of derision? Or is it because of some other aspect of the character or the way the character is perceived by those rendering him that isn't explicit? That Kissinger, like Goodman's parents, is a Jew and Holocaust survivor might have been an inspiration and basis for humanizing this character in the opera. Instead, he seems only to have aroused the kind of malice that sophomores, or Jewish adolescents who want to deny and reject the burden of their ethnic heritage, harbor for their parents.

Whatever the ingredients, Kissinger was destined to become in such troubled hands culture's old standby--the lecherous, treacherous, power-mad Jew, a figure that reemerged after the Holocaust not so notably among conservatives and rightists as among leftists, intellectuals, and artists. Lest we forget, Nixon in China and Klinghoffer were written in the heyday of a great international resurgence of anti-Semitism, fueled by blame and scapegoating of America, Israel and the Jews for the entire global and historical phenomena we call jihad; a blame centered in the circumstances of the Palestinians; a blame that continues. Goodman, whose admitted anti-Zionism can't help but raise questions of internalized anti-Semitism, would appear to share these sentiments with no small number of other Jewish and non-Jewish socialists, progressives, intellectuals and artists. In the wake of Jewish indignation and criticism following the premiere of Klinghoffer, including from members of the Klinghoffer family who have denounced the opera as anti-Semitic, and likewise in the context of her marriage to the British poet Geoffrey Hill, Goodman converted to Christianity, becoming an ordained Anglican minister.

Alice Goodman

Meanwhile, how does the character of Kissinger fit into the greater operatic canon? If you compare the depiction of Kissinger in Nixon in China with Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger, the similarities are striking. Both are Jewish caricatures whose Jewishness is vehemently implicit rather than explicit. Both are dehumanized, cartoon scapegoats for all the cultural wrong surrounding them. Neither has a moment of self-expression that could invite any level of identification or sympathy. On the contrary, the audience can only have loathing and contempt for both of them.

The most notable of efforts to mitigate Wagner's malevolently satirical portrait of Beckmesser--incidentally as scholars like Barry Millington, Marc A. Weiner and Paul Lawrence Rose increasingly identify anti-Semitism as intrinsic to Die Meistersinger--came in the recent period with the casting of one of Germany's greatest real-life mastersingers, Hermann Prey, as Beckmesser in a number of stagings of the opera, including at Bayreuth and at the Met. Alas, Beckmesser's music is so relentlessly ugly and unsingable that not even Prey could render more than a modicum of dignity to the role. Such is the audience's stirred-up contempt that when Beckmesser is beset by a mob of Volk and beaten to a pulp, you want to join in; but perhaps a little less so when Beckmesser is Hermann Prey. If the Kissinger caricature weren't so poorly drawn, the same inclination would be true of his portrayal in Nixon in China. Would the problem be solved if we cast a great and beloved leading singer, a Bryn Terfel or Rene Pape, as Kissinger?

Goodman has recently said that she looked into herself in her portrayals of all the characters in Nixon in China, including Kissinger. But this admission seems disingenuous, both after the fact and defensive. Kissinger has also been described by the opera's co-creators as a "buffo" figure, as if the casting of him in this stock operatic role somehow mitigates, justifies and supersedes the other issues and questions any more than such an explanation would suffice for Wagner's treatment of Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger.

Nixon in China is otherwise an original creation that qualifies as one of America's and contemporary opera's notable works. I was an early admirer of Peter Sellars' gift for rendering opera and theater more vital for contemporary and younger audiences, from his first production of Don Giovanni in a Massachusetts high school gymnasium with the Don as a heroin addict in Spanish Harlem, on through to his signature Mozart productions of The Marriage of Figaro set in Trump Tower and Cosi fan Tutte set in a Cape Cod diner. So I was curious about his later productions --a televangelical Tannhauser, a homoerotic Tristan, The Merchant of Venice with a black Shylock, The Magic Flute, Orlando, Theodora, St Francois D'Assisi, even his cell-phone Othello. Sellars' daring retained its appeal, even as the whole deconstructive approach to opera and theater he had spearheaded began to deflate. Though I liked what Sellars was trying to do in theory, the results seemed in increasingly uneasy alliance with the artworks themselves; and though I did see all the Adams operas he collaborated on, I made little effort to see the other Sellarsizations of classics. Peter Sellars deserves premiere credit for what became the predominant approach to theater and opera in our time. But after those early Mozart productions, nothing he himself staged approached the achievement of, say, the Patrice Chereau Ring cycle production at Bayreuth.

I've also admired the work of John Adams. I found some of the pieces in Nixon in China to be exhilarating, and some of his music for Klinghoffer and Dr. Atomic to be expressive and beautiful. Sellars and Adams are talents I've wanted to be on board with. But so troubling a figure is Alice Goodman and so troubling their opera's portrayal of Kissinger that, as with Wagner's work in the wake of the publication of his epochal hatefest, "Judaism in Music," the rest of their work feels thereby tainted. Just as I can never again be really comfortable with Wagner, I can likewise never again be really comfortable with Goodman, Adams, Sellars, their operas or their stagings.

In fact, so on guard did I become regarding their work that I experienced a paranoid illusion during the premiere of Dr. Atomic at the Met. Not so unlike the way Pat Nixon imagines that she sees a rapacious Henry Kissinger in the ballet, The Red Detachment of Women, in Nixon in China, I imagined that the chains that covered the big atomic bomb that hovered over nearly all of the proceedings in Dr. Atomic were arranged to suggest a star of David covering the globe. (Full disclosure: Neither my partner Arnie, with whom I attended the performance, nor anyone else I know who saw Dr. Atomic felt they saw this. Nor was any such pattern discernible in my subsequent perusals of photographs of the production.) Dr. Atomic was directed by Penny Woolcock, who also directed a film version of The Death of Klinghoffer based on the opera for British television.

Whatever my own misgivings or apprehensions, everyone should be free to see and admire this or any other art. But it should not be demanded that I do, or that I endorse the greatness of such art as surpassing and transcending any and all other concerns and feelings. Meanwhile, whatever else the team of Adams, Goodman and Sellars has achieved, however ostensibly humanitarian and laudable their professed intentions, it's difficult for me to get past their creation of Kissinger, which I can't help but see as the ugliest and most hateful Jewish caricature in all of opera, the first real successor to Beckmesser, Alberich and Mime. I can't help but sense the old "Protocols of the Elders of Zion" wafting within and about their oeuvre.

Which brings us back to Klinghoffer, in which the Klinghoffers are portrayed as stereotypical Jewish-American materialists. That the opera contains a number of small moments, details and vignettes that show the humanity of all the characters, Jewish as well as Palestinian, noble and less noble, does not resolve the problem that lies at the heart of this opera's composition and presentation: its globalization of circumstances, grievances and evils. In 2003, Edward Rothstein updated his stage review of Klinghoffer to a critique of Penny Woolcock's filmed version for its affirmation of "two ideas now commonplace among radical critics of Israel: that Jews acted like Nazis, and that refugees from the Holocaust were instrumental in the founding of the state, visiting upon Palestinians the sins of others."

"The Judaism I was raised in was strongly Zionist," said Alice Goodman in an interview in the Guardian in 2012. "It had two foci almost - the Shoah [the Holocaust] and the State of Israel, and they were related in the same way the crucifixion is related to the resurrection in Christianity. Even when I was a child, I didn't totally buy that. I didn't buy the State of Israel being the recompense for the murder of European Jewry, recompense not being quite the right word, of course. The word one wants would be more like apotheosis or elevation."

[Following the presentation to our class of a Holocaust documentary when I was 8 years old], Goodman continued, "our very traumatised junior rabbi quoted the song that begins, 'Cast out your wrath upon the nations that know ye not.' In Hebrew it is, 'Cast out your wrath upon the goyim [a disparaging term for non-Jews],' which is what he said. My infantile brain thought, 'No, that's not the right answer.' That thought is the thing that's brought me here. And it has to do with Klinghoffer as well."

Since Goodman knows that most Israelis, like her parents, are not very religious, why is she basing her judgments on impressions she admits were made on her when she was preadolescent?

In anticipation of the ENO premiere of The Death of Klinghoffer there was a flurry of advance press, including the interview with Goodman. Lisa Klinghoffer, one of Leon and Marilyn Klinghoffer's daughters, is also quoted in the Guardian: "The opera displays thoughts and feelings about our parents and friends they never had or expressed. Prior to the production, I tried to tell Peter Sellars [the director of the original staging] about our parents, but he said that he did not want or need to hear them. To us he was willing to distort the image of our parents and to show a stereotypical picture of the 'fat cat' American Jew to express his political agenda."

Setting aside the issue of Alice Goodman's, Sellars' and Adams' ideological background and orientation, a case can always be made for the motivation and psychology of fascists. Why did the Nazis do what they did? What did the Jews do to make the Germans so angry at them? There must have been reasons for it. Fat-cat wealth and arrogance! Bolshevism! Why did Osama bin Laden hate America, Israel and the Jews as much as he did? There must have been reasons for this too. Colonialism! Likewise the Taliban's blowing up of Afghanistan's great Buddha statues. Infidels! In the case of the Palestinians, who live under conditions of occupation by Israel but who have never been willing to recognize Israel's right to exist and who voted to be co-governed by Hamas, an Iran-backed terrorist organization unremittingly committed to Israel's destruction, the issues might appear to be more complicated. Even so, it would seem that the commission of fascistic and terrorist acts and atrocities is far more a matter of prosecution and prevention than compassion, understanding and forgiveness. That proved to be true of Nazism and it is likewise true of the greater arc of Islamic extremism and terrorism. The challenge here would seem far less to try to explain, understand, mollify and forgive terrorism and extremism than to stop and prevent it. However reasonable and even laudable some of its intentions and whatever the qualifiers of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, The Death of Klinghoffer does more to obscure, retard and inflame that process than help it.

As Richard Taruskin concluded in his New York Times response to the controversies surrounding the postponements and cancellations of scheduled productions of The Death of Klinghoffer in the aftermath of 9/11, "If terrorism -- specifically, the commission or advocacy of deliberate acts of deadly violence directed randomly at the innocent -- is to be defeated, world public opinion has to be turned decisively against it. The only way to do that is to focus resolutely on the acts rather than their claimed (or conjectured) motivations, and to characterize all such acts, whatever their motivation, as crimes. This means no longer romanticizing terrorists as Robin Hoods and no longer idealizing their deeds as rough poetic justice. If we indulge such notions when we happen to agree or sympathize with the aims, then we have forfeited the moral ground from which any such acts can be convincingly condemned...In the wake of Sept. 11, we might want, finally, to get beyond sentimental complacency about art. Art is not blameless. Art can inflict harm."

So was there a lesson to be learned by the co-creators of Nixon and China and Klinghoffer from the experience of Wagner? Yes, there was. It's an expansion and twist of the famous saying attributed to Santayana: Those who do not learn the lessons of the past are condemned to repeat it. But even when they do learn those lessons, they are likely to repeat the past, so long as they think they can get away with it. Wagner not only got away with it, it's increasingly clear that his career and works knowingly and greatly benefited from the attendant and subsequent controversies. Intentionally or otherwise, the controversies surrounding Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer are playing out along a comparable trajectory.

From its recent and current repertory, perhaps the Met should consider a new option for its mini-series subscriptions: Die Meistersinger, Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer.

______________________________________________