On Sept 20, opening night of the current Metropolitan Opera season, I ventured to Lincoln Center to observe what I understood would be an organized Jewish protest of the Met for its planned presentation of the opera The Death of Klinghoffer. The Oct 20 Met premiere drew an even larger demonstration. I saw the US premiere of the opera at BAM in 1991 and had little inclination to experience it again, notwithstanding its subsequent elimination of an early scene underscoring the opera's conceptualization of Leon and Marilyn Klinghoffer as stereotypical Jewish-American materialists.

Apart from the controversies about the opera's politics, the bigger problem with Klinghoffer is its weakness as music drama. Though it has passages of expressive music and some moments that are insightful, challenging and moving, most of this quasi-oratorio is textually opaque and musically inert. By comparison, and apart from its conspicuously outsized caricaturing of Henry Kissinger, Nixon in China is a more coherent, dramatic and engaging work, though it, too, inevitably deflates. Though I was more drawn to attend that opera's revival by the Met in 2011, I finally decided against doing so because of my discomfort with what seemed to me its covertly anti-Semitic depiction of Kissinger.

In the wake of all the protest, a number of artists, intellectuals and other distinguished persons have responded positively to Klinghoffer. As quoted in the Wall Street Journal, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg found the opera to be "a most sympathetic portrayal of the Klinghoffers...both of [whom] come across as very strong, very brave characters...There was nothing anti-Semitic about the opera." Justice Ginsburg also disputed claims that the opera glorified terrorism. "The terrorists are not portrayed as people that you would like. Far from it...They are being portrayed as bullies and irrational...There is one very dramatic scene of a Palestinian mother raising this child, his toy is a gun from when he's five years old, and she's raising him so that he will one day do a very brave act that will result in his own death and then he will go to paradise...It was chilling."

Prior to the Met premiere, I had already shared my more critical viewpoint on Huffington Post in my essay, "On The Future of Wagnerism, Part 3: Beckmesser, Kissinger and The Klinghoffer Controversy." Because a number of the protesters were calling for the Met to cancel the opera, as an opponent of censorship, I did not feel I could join their ranks. But as a Jew who is concerned about past, current and future resurgences of anti-Semitism, I was heartened and inspired to see such organized, courageous and spirited Jewish protest.

The Klinghoffer clashes bring to mind a comparably sentinel episode in the history of minorities, art and censorship, around the William Friedkin movie, Cruising, starring Al Pacino, in 1979/80. Just as Klinghoffer, as originally created, was seen by many Jews as yet another anti-Semitic attack on Jews, so was Cruising seen by gays as yet another homophobic attack on gay people. In both cases, the works themselves were far from being the worst of their genres and their creators did not explicitly endorse extremist views.

Friedkin was a kind of macho Hollywood liberal who may not himself have been sure what he thought about gays but who didn't think of himself as homophobic and who believed he was making an artistic contribution. Similarly, composer John Adams, librettist Alice Goodman and director Peter Sellars, the co-creators of Klinghoffer, see themselves primarily as artists and humanitarians and don't think of themselves as anti-Semitic or endorsing terrorism. Fortunately for both communities but unfortunately for the artworks and their creators, both works struck sensitivities that ignited historical protests.

Just as cohorts of Jews called for the cancellation of Klinghoffer, legions of gay people, spearheaded by influential Village Voice columnist Arthur Bell, were determined to shut down the filming of Cruising. At that time I myself was writing a piece for the gay press that asked "Why is Hollywood Dressing Gays to Kill?" It complemented the work of our extended family member Vito Russo, (who was my life partner Arnie Kantrowitz's closest friend and the author of the celebrated work of gay consciousness, The Celluloid Closet, about the history of homosexuality and film). Like Arthur and many other GLBT people, we -- Arnie, Vito and I -- were fed up with the "necrology," as Vito called it, of gay people in film, the vast majority of whom ended up dead -- murdered or having committed suicide, imprisoned and/or insane. This was a genre and tradition that Friedkin's film, a dark look at the gay s-m scene and gay murder, was clearly going to play right into. Thus did Cruising become a lightning rod for the pent-up gay anger of decades.

Alas, there was a problem with Bell's call for a shutdown of the film, a problem Vito and Arnie realized almost immediately. Although they felt deeply in sync with this gay activist protest, they did not feel they could go the full distance of calling for the banning or censorship of this film or any other artwork, no matter how otherwise biased, exploitative, smarmy or even dangerous. As with Jewish concerns that Klinghoffer would inflame anti-Semitic violence, especially in Europe, what seemed most urgent in calling for the banning of Cruising was its potential to incite more hate crime against gays, who already had sustained sky-high rates of violent assault and murder, savagery that continues unabated today in Russia, Africa, throughout the Islamic world and otherwise globally.

It was difficult to keep one's neutrality around the issue of the film's potential to incite violence, but the censorship boundary prevailed for Arnie, Vito, other gay observers and me. (I was acquainted with Vito but didn't meet Arnie until 1981.) Neither Arnie nor Vito marched with the protesters. Nor, as I recall, did I. In the aftermath, just as Klinghoffer was adapted to take out its most offensive references, Cruising was adapted to include a new gay-affirmative line or two under pressure from the protesters. Filming was completed and Cruising opened to mostly critical reviews. Eventually, of course, the controversy died and the film took its place in the annals of film as an historical curiosity rather than anything more controversial, substantial or enduring. Apart from some favorable reviews, one critic calling it a "masterpiece," a similar trajectory followed for Klinghoffer which is likely to enounter a comparable fate in the annals of music.

Although the Cruising episode wasn't a shining moment for the history of censorship and art, it was a shining moment for the history of the gay civil rights struggle. And I would propose that whatever its comparable tarnishing of the sanctity of art, the Klinghoffer protests were likewise a shining moment in the history of minority and Jewish consciousness and activism, here in America as well as globally.

Not surprisingly, our critics were not only safely against censorship but as such safely against the protesters. From that vantage point they could return to their routines of being performance reviewers and sanctity-of-art guardians rather than more independent and in-depth observers. Apart from the viewpoint of preeminent musicologist Richard Taruskin that had been published in the New York Times in defense of the Boston Symphony's cancellation of a scheduled concert performance of Klinghoffer in the wake of 9/11, no mainstream take on the Met Opera confrontations gave in-depth credibility or respect to Jewish concerns or the Met's decision to cancel a live broadcast of the production, though several of the critics mentioned the program statement by the Klinghoffer daughters, who consider the opera to be anti-Semitic, dishonest and dishonoring of their parents. Notably, most critics chose to showcase the more extremist protest placards and statements at the expense of weighing more challenging ones.

In the New Yorker, Alex Ross did note that both former Governor David Paterson and former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, an opera lover who otherwise admires Adams' music, weighed in at the rally with concerns about the opera's potential to stoke hostilities. Ross then proceeded to expose the rally as little more than a forum for fanaticism. "The most aggressive rhetoric came from Jeffrey Wiesenfeld, a money manager who has also worked as a political operative," Ross observed. "A few years ago, Wiesenfeld won notoriety for seeking, unsuccessfully, to deny the playwright Tony Kushner an honorary degree, on account of Kushner's criticisms of Israel. Wiesenfeld led the Klinghoffer rally, and he had much to say. "This is not art," he thundered. "This is crap. This is detritus. This is garbage." He declared, as he did at an anti-Klinghoffer event last month, that the set should be burned. He made a cryptic joke to the effect that, if something were to happen to Gelb that night, the board of the Met would be the first suspects. The rally went on in that vein."

Wiesenfeld is a former CUNY trustee who was quoted in the Forward as having "once said that his mother would have called playwright Tony Kushner a 'Kapo.'" Alas, Wiesenfeld's remarks recalled the bitter and protracted opposition to the New York City gay civil rights bill by conservative and orthodox Jews. Also concerning at that time, however, were some of the angrier reactions to that opposition, including from some gay Jews. Never underestimate the power of justification--whether we're talking about Roy Cohn, Henry Kissinger, Bernie Madoff or the acts of homophobic or Islamophobic Jewish bigots and zealots -- to "justify" judgments and resentments, including those which abet anti-Semitism. Meanwhile, if the Klinghoffer rallies had any other value or invited any deeper level of analysis, that's not something you were going to find in the otherwise defensive coverage of our leading music critics.

If the critics did have any misgivings about their stances, they needed only to look for reassurances to Peter Gelb (who is also Jewish) and The New York Times editorial board as well as a wide range of Jewish artists and intellectuals, the majority of whom all too easily and quickly embrace the dominant philosophy of "art uber alles" at the expense of their own minority consciousness and dignity. "For people to call me a self-hating Jew is so ludicrous that it's beyond chilling," Gelb told the Forward.

In the bigger picture, the splitting of Jewish opinion is reminiscent of that which unfolded in Europe under Nazism: between the educated, assimilated Jewish intellectuals, artists and kultur lovers on the one hand and the Ostjuden--the loud, vulgar eastern European and Russian Jewish rabble--on the other. Meanwhile, as today's pogroms against gays in Russia worsen, Gelb has yet to issue a statement of protest on behalf of the Met, which continues to showcase an unprecedented array of politically silent Russian artists, most notably Anna Netrebko and Valery Gergiev, both of whom remain unapologetic pals of Vladimir Putin.

Several years ago in Los Angeles, some Jews protested the L.A. Opera's plans for a new Ring cycle. They questioned the priority of appropriating large sums of money and resources for the tainted works of one of history's most virulent anti-Semites. Although they were aggressively defeated and plans for the cycle proceeded apace, these protests proved to be a harbinger of the Klinghoffer confrontations.

What would have happened if the educated and upper class Jews of Wagner's time--especially those in Wagner's own circles and throughout the music world of that period--had been more forthright, organized and determined in protests of Wagner's anti-Semitism, like the Jews here who protested Klinghoffer? Might such demonstrations have made a difference in Wagner's choice of subjects or otherwise in the expression of his prejudices? Might Wagner have been influenced--the way Dickens was influenced to respond with more sensitivity to Jewish concerns about the character of Fagin--to write a retraction or modification of his infamous diatribe, "Judaism in Music"? Unlikely, perhaps, but if a leading anti-Semite like Henry Ford could be thus influenced, albeit via anti-defamation litigation, why not Wagner?

If Jews had been more organized and outspoken in Nazi Germany, albeit at their peril, might the course of history have been different? Hannah Arendt seems to have thought so, and in our time likewise one of her disciples, Larry Kramer, the great gay and AIDS activist and author of The Normal Heart. Kramer was inspired by Arendt in the conviction they appeared to share that -- for gay people in their greatest crisis, like the Jews in theirs -- silence equals death.

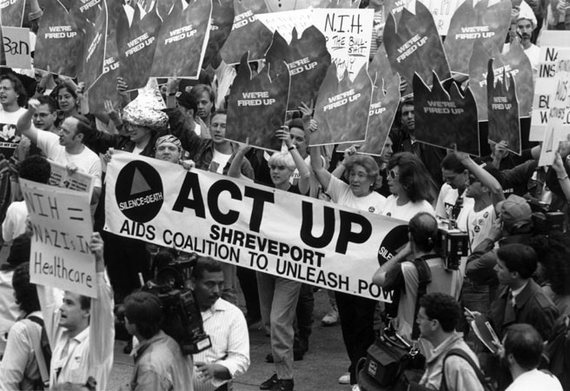

Which brings us to another example of gay protest pertinent to our discussion, the aggressive demonstrations of the monumentally heroic and successful AIDS activist organization founded by Kramer: ACT UP. At their most confrontational, this organization used extremely provocative rhetoric with highly confrontational but technically peaceful tactics to pursue its agenda of influencing AIDS research and health care. Ed Koch and Ronald Reagan were repeatedly denounced by Kramer and ACT UP as murderers and mass-murderers, as Hitlerian, as Nazis committing genocide. As with some of the more extremist statements of those protesting Klinghoffer and Cruising, I could not go to these same lengths myself. I could not carry banners calling our gay and AIDS nemeses, including people like Anthony Fauci, Nazis and Hitler and accusing them of genocide. But I did march with ACT UP and did carry a banner that read: "We Need Experts, Not Bigots." The point here is that I marched in solidarity with Larry Kramer and ACT UP, even though I couldn't endorse some of his and ACT UP's more extreme rhetoric and tactics. My reaction to the protesters of Cruising and Klinghoffer were strongly analagous. I couldn't agree with their exaggerations of the film's or opera's intentions or dangers and their calls for more extreme responses, but I felt in solidarity with their greater concerns.

In the case of Klinghoffer, as in the case of Cruising, the bottom lines for me are simple. I am concerned about some of the rhetoric and tactics of some gay radicals, but I am a lot more concerned about homophobia. While I share humanitarian concerns about the Palestinians and Israel's occupation of disputed territories, I'm a lot more concerned about Islamic aggression and anti-Semitism, as well as homophobia.

As for the value of art when weighed against the value of life, in Part 3 of "On the Future of Wagnerism," I told the story of my partner Arnie asking his boyhood German-American friend if Wagner's art were more important than the lives of 6 million Jews. The answer was "yes." Needless to add, I do not agree. In fact, though I've yet to betray my standard of not endorsing censorship, if I were asked to press a button that would eliminate Wagner's art from history, memory and the future as the cost of changing the course of the history of World War 2 and its genocides or the possibility of their recurrence, my finger would press that button so quickly and so hard it would probably break.