Vito Russo, the legendary gay and AIDS activist whose achievements have already earned him a biography and several film documentaries, is best known as the author of The Celluloid Closet and as a co-founder of GLAAD (Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation)

by Lawrence D. Mass

For the last three years, New York City has been host to The "Last Address" Tribute Walk. The event is coordinated by Alex Fiahlo, programs manager of Visual AIDS, an organization that "utilizes art to fight AIDS by provoking dialogue, supporting HIV+ artists, and preserving a legacy, because AIDS is not over."

Commencing with a screening of Ira Sachs's short, moving film, Last Walk, which lingers quietly and respectfully outside the last addresses of a number of artists and writers who died of AIDS-related illnesses and conditions, Fiahlo then conducts a walking tour to a selection of those addresses, where there are readings of remembrance and tribute by colleagues, friends or loved ones of these artists. Among those whose homes were visited in the film are Keith Haring, Hibiscus, David Wojnarowicz, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Harold Brodkey, Robert Mapplethorpe, Reinaldo Arenas, Charles Ludlum, Assotto Saint, Jack Smith, Ethyl Eichelberger and Vito Russo. http://www.visualaids.org/blog/detail/alex-fialho-writes-about-his-last-address-tribute-walk

This will be the first year that Vito's home will be included in the walking tour and I was honored to be asked to speak about Vito outside his home, where I spent so many evenings, from the earliest period of having met him and of the epidemic in 1980-81 until his death in 1990. For the tour, I plan to read several passages from the wonderful biography of Vito, Celluloid Activist, by Michael Schiavi, as well as from the foreword to the revised Stonewall classics edition of Under the Rainbow by my life partner, Arnie Kantrowitz.

In the space I have here, and as we approach the 25th anniversary of Vito's death from AIDS, I would like to personally remember Vito, whose friendship was one of the gifts of my life. What warm memories I have. As Arnie's closest friend, Vito became family. Together with their other closest friend, NYC gay civil rights pioneer Jim Owles, I had married into an extended family of giants of the gay liberation movement.

Even though Vito was someone we saw and talked to and about continuously, such were his aura and energies--his "sparkle and charisma," as Arnie captured it--that just to be in his presence, at his home, ours or anywhere else, always felt like a special event. Whether showing us snippets of new films with gay characters, actors, themes or issues, old clips of Bette Davis (Arnie's favorite actress) and Miriam Hopkins in Old Acquaintance, or regaling us with his favorite line from his favorite film, Caged, about women in prison: "Ok, you tramps, pile out. It's the end of the line!", Vito was always vibrantly present, always on, always a star, the brightest in our lives. Incidentally, we inherited Vito's Caged poster which greets you now as you enter our apartment, on apposing walls of which are two other Vito posters, one from Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt, the 1989 academy-award winning documentary featuring Vito, and another from a New York City Gay Men's Chorus Night at the Movies that Vito hosted. It was always great to see the pictures of his favorite star, Judy Garland, that festooned Vito's apartment and the film clips of her he probably watched more often than Arnie saw his favorite film, Gone With The Wind. (How we all would laugh at the thought of "Scarlet Kantrowitz"!) Garland was, after all, the greatest singing actress in the history of film as well as the premiere gay icon whose death, as legend has it, sparked Stonewall. We loved her too, but it's Vito we remember most from all those Judy moments we shared with him.

Whether we were playing Yahtzee, Risk or poker, dishing the latest dish about this or that closet case or star (so often one and the same), celebrating our birthdays together, ganging up on "the Kantrowitz," as Vito called him, for always somehow being "the good one"; whether we were catching pearls of wisdom, fact and insight from his encyclopedic knowledge of film or catching him munching on the Mallomars he kept refrigerated and with which he always could be counted on to spoil his appetite for dinner; whether savoring the impressive Italian pasta sauce he made from scratch, ignoring the burping and flatulence that increasingly plagued him as AIDS advanced, or massaging his legs for the pain from the large KS lesions that covered his body, being with Vito was always a family connection, and always a gift.

So many treasurable moments. The first that comes to mind was also the last, in the sense that it happened just after Vito died, in fact as Arnie, Jim Owles and I were on our way to his memorial service at Cooper Union in New York. Featured speakers included Mayor David Dinkins, who had visited Vito in the hospital, and Larry Kramer, who famously began his comments with "We killed Vito." Alas, the soundtrack of the service was lost because of a recording error. Our taxi driver, apparently bitter about his life, chose our ride to displace his anger." Life is terrible," he inveighed. "No money, no women, no friends!" "But that's just not true," I shot back. "We're on our way to a memorial service for our beloved friend, who also had no money, but who had more friends, so many of them women, than anyone I've ever known." What I'd said was impressively true. Vito was always broke, yet always managed to keep earning his way, never exploiting his staggering array of friends, many of them well-heeled and virtually all of them bending over backwards to help and love him in every way we could, even as we failed to rally in time the much greater forces needed to save him. I can't recall anyone who disliked or who was seriously alienated from Vito, apart from some misanthropes from the next generation of Zine queers, who criticized him for being too mainstream.

One of those well-heeled friends was the leading New York socialite, charity doyenne and GMHC buddy pioneer and patron Judy Peabody. They immediately struck up a genuine friendship, calling each other at all hours, laughing and chatting intimately about everyone and everything. Judy was just one of the many stars in Vito's orbit. Bette Midler, Peter Allen, Elizabeth Taylor, Lily Tomlin, Ian McKellen, Harvey Fierstein...the list is endless. The thing about Vito and these friendships is that they were all genuine. It's hard to imagine anyone better at making and keeping friends. When Mayor Dinkins visited Vito, Vito confided to him personally, as he would to any good friend, urging him to be true to himself and choose principles over politics and popularity.

However glamorous and beloved a star Vito was in our firmament, his life's work was as serious and revolutionary as it was urgent. Before meeting him, I was keyed into his writing, especially The Celluloid Closet, which addressed a key perpetrator of what would eventually be called gay genocide by his increasingly close friend and comrade-in-arms Larry Kramer: the relentless representation of GLBT people in films and media as killers and psychopaths, as evil, sick, demented. The Celluloid Closet was the first book to catalogue what Vito called the "Necrology" of GLBT people in film. At that time I was writing my own first pieces in the gay press, one of which was called "Why is Hollywood Dressing Gays to Kill?" for the New York Native, for which I also wrote what became the first press report and weeks later the first feature article on AIDS in 1981. The previous year I had covered the trial of the serial killer John Wayne Gacy in Chicago for Christopher Street magazine. Individually and together, these developments seemed to have the potential, in the wake of the Dan White trial for the assassination of Harvey Milk in San Francisco, of igniting an unprecedented backlash.

If there is anything that unites the struggles against AIDS with those of homophobia in the arts, it's the issue that is captured by the ACT UP logo, Silence = Death. Just as Vito fought so bravely and lovingly to open the closet doors of cinema, so did he struggle mightily to open the eyes and hearts of the world to AIDS. Yet here is where another of Vito's qualities was revealed--the unconditionality of his love. Although he could be fiercely angry, disappointed, critical and activist, and a true leader as such, he was inevitably forgiving, and without lingering personal bitterness; and he continued to love us all, including closeted stars and celebrities who just couldn't for whatever reasons of circumspection and career bring themselves to come out publicly but whose confidences and friendships he simply would not betray, even when under considerable pressure to do so. Likewise those within his own and extended gay families who fell short of expectations of who and what we could be and do, especially as AIDS raged on. In a moment that brought me to tears, just before one of his last public appearances, also at Cooper Union, I found myself once again inarticulate in trying to express to Vito how much we all loved him, how much he meant to us, how grateful we were for all he had done, how sorry we were that we hadn't fought harder and achieved more, better and faster. As Larry Kramer has often observed, the epidemic might have been quashed sooner and a lot more lives saved, including Vito's, had everybody's efforts been redoubled. I felt totally inarticulate and failed in my effort to communicate all this, but as our eyes met, he said, "I love ya, Lar."

Vito was especially inspiring to me in my own work on opening the closet doors of the worlds of music and opera. I'd hoped eventually to put together a collection of my essays, interviews and reviews, the working title of which was "Musical Closets," a worthy project that was never completed. Alas, there still is no overview work, no Celluloid Closet, on homosexuality in music and opera, though there are now, thanks in no small measure to Vito's pioneering efforts, a number of books on homosexuality and the fine arts.

The Celluloid Closet quickly became a classic that remains a premiere reference for GLBT experience and treatment in the arts, a standard that paved the way for subsequent studies and documentaries, and with which all other such work will continue to be compared. As adapted for film by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, The Celluloid Closet was nominated for numerous awards, and GLAAD susbequently named an annual Vito Russo Award to recognize openly GLBT achievement in fighting homophobia in film and the media.

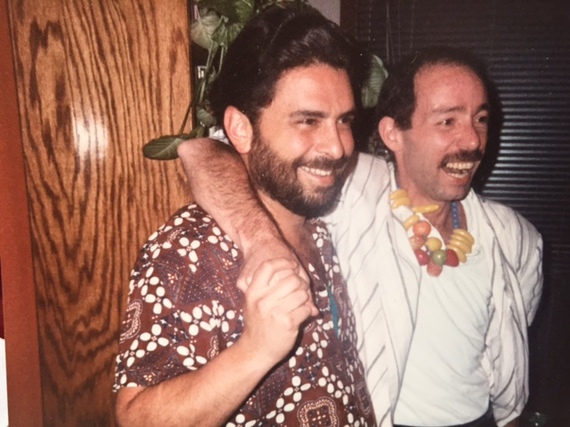

Vito with his agent and close friend, Jed Mattes, who was at Vito's hospital bedside when he died from complications of AIDS November 7, 1990.

Alas, there is little of the fabulously engaging star, leader and persona that was Vito Russo himself in the 1995 film of The Celluloid Closet, but we are fortunate that Vito's appearances on film did not end there. There is ample footage of him in Common Threads, and also in Jeffrey Schwarz's 2012 documentary of Vito's life and work, Vito. As is now the case with Larry Kramer following the release of Jean Carlomusto's documentary for HBO, Larry Kramer in Love and Anger, there is now enough of the real Vito Russo preserved on accessible documentary film to give a genuine sense of who that person was, what he was like, why he was so important, and why he was so beloved.

As witnessed by Arnie and myself from behind Vito and Larry Kramer, and as recounted by Michael Schiavi in Celluloid Activist, the Gay Pride parade, Vito's last in 1990, passed Larry's apartment on 5th Avenue just above 8th Street. On Larry's balcony, Larry and Vito locked arms, acknowledging the roars that kept erupting from the passing throngs below. "Look Vito," Larry said. "These are our children."

RIP Vito. When you passed from our lives, the brightest of its light--sunlight and starlight--went with you. You may not have lived to see the AIDS treatment that eluded you by only a few years, nor did you live to see the "end of AIDS," as we are buzzing about it now. But your spirit and legacies of activism will live on, as will the love and gratitude of all those who knew you, all those whose lives your activism was key to saving and ennobling, including those younger and countless who did not have the gift of knowing you personally, "our children."

photos from the private collection of Larry Mass

references from The Celluloid Activist by Michael Schiavi and the obituary on Vito Russo by Arnie Kantrowitz, Outweek, 11/21/90

___________________________