Where did strangers answer the "call of nature" in Victorian London?

At the start of Victoria's reign, options were limited. Some pubs had primitive outdoor "urinals" -- no more than a vertical slab of stone -- but men largely resorted to the nearest alley. Residents living near to much-frequented spots regularly wrote letters of complaint to local authorities. Signs were erected, bearing the legend "Commit No Nuisance." Property owners installed "barricados" of wrought iron on befouled walls, angled strips of grooved metal, designed to deflect the noxious liquid onto the wrongdoer's shoes. The problem was, however, endemic. The fountains of newly built Trafalgar Square were "polluted by brutes in human shape" within days of their opening.

Urine deflectors fixed to wall in Clifford's Inn Passage, Fleet Street

Women were expected to be more "decent" in their behavior; but the dire conditions of the capital's slums meant that their inhabitants, both male and female, frequently had recourse to neglected back-streets. Along the river at Bermondsey, ramshackle privies were constructed on decking over the Thames -- their plummeting deposits providing an unpleasant spectacle for tourists on passing steamboats. There were, fortunately, alternatives for those women whose higher social standing did not permit al fresco relief. The coach-owning classes were not above drawing the vehicle's blinds and using a bordalou (a gravy-boat-shaped chamber pot). Equally, female shoppers might pay a call at a confectioner's or milliner's, buy some trifle and politely request use of the owner's privy -- but only as a personal favor.

Indecency by Isaac Cruikshank, 1799

There was an obvious solution -- the public restroom.

Sanitary innovation was already on the cards. The 1840s saw the tentative beginnings of a vast metropolitan sewer-building project, and the construction of public baths and washhouses. Public toilet facilities, were equally desirable, according to reformers. But would anyone respectable -- especially "modest" middle-class females -- feel comfortable performing their private business "in public"? Some considered the thought positively shocking.

The idea would be tested at the "world expo" of the 1851 Great Exhibition. An enterprising plumber, George Jennings, was contracted to provide "retiring rooms" with the latest sanitaryware. He met with great success. A remarkable 827,820 persons, both sexes, used the toilets, over a period of six months. The Royal Society of Arts, dedicated to fostering technological innovation, was so impressed that it promoted its own scheme. Two trial suites of rooms -- with toilets and washing facilities, manned by attendants -- were set up in existing commercial premises in central London. Unfortunately, this venture proved an utter disaster. Less than a hundred individuals used the toilets during a whole month; only twenty eight were women. Modesty seemingly prevailed, once people stepped beyond the hustle and bustle of the Exhibition. Both establishments were swiftly closed; and a doleful report on the subject concluded "An Englishman rarely requires anything more than an ordinary urinal in the streets."

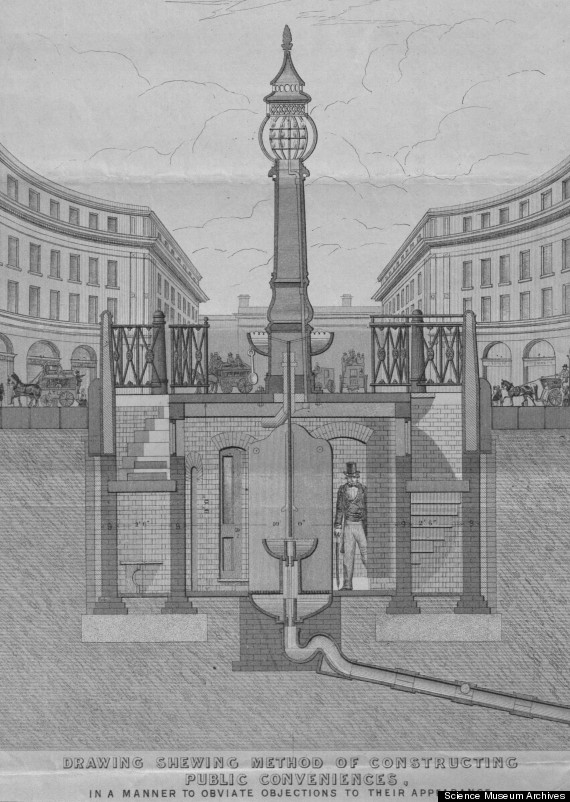

George Jennings steadfastly believed otherwise. He would spend the next decade trying to persuade London's local authorities that there was a demand for public water closets -- particularly amongst respectable women. Time and again, he was rebuffed. He offered to build and finance public restrooms himself. He was told that his "objectionable contrivances" would shock modest females. Jennings then came up with an ingenious (one might almost say Freudian) solution to the "modesty" problem -- building conveniences underground -- but this, too, was rejected. Prudish anxiety was also mixed with concerns about male sexuality. The capital's urinals, which had evolved into more elaborate enclosed cast-iron affairs, were notorious as places for homosexual encounters.

George Jennings' Plan for an Underground Convenience (Courtesy of Science Museum Archives)

Victorian women would, however, challenge the status quo.

The Ladies Sanitary Association, founded in 1857, mostly issued pamphlets on household cleanliness (with titles like "The Black Hole in Our Bedrooms"). In 1878, it ventured beyond the domestic sphere. Rose Adams, the organisation's secretary, wrote to every metropolitan local authority in London, demanding public restrooms. The argument, said Miss Adams, was both moral, sanitary and economic: "The increasing number of women (working) of all classes who travel about London daily renders such provision of serious moment."

The response was mixed. Some authorities decided that the existing facilities in a handful of railway stations were sufficient. Some balked at the LSA's suggestion that "a free W.C. should always exist at a paying station" -- provision specifically for the poor opened up all sorts of further anxieties about mixing social classes. One medical official conceded that the provision solely of urinals was "a selfish inequality." Another, James Stevenson, wrote a lengthy report supporting the proposal. He denied myths that women were better able to exercise physical self-control. He even opaquely alluded to pregnancy and menstruation.

There was considerable discussion; but no action. When the City of London introduced the first underground convenience at the Royal Exchange in 1885 -- borrowing Jennings' idea only after his death - it was for men only. Yet the LSA's campaigning had an effect. Slowly but surely, the subject moved from the letters pages of medical journals into the national press. Finally, in 1889, a magnificently appointed municipal woman's underground convenience was opened in Piccadilly Circus. The location was significant -- this was the heart of the West End, the burgeoning shopping district, whose department stores were attracting increasing numbers of prosperous middle-class women into the heart of the metropolis. Their business was valuable; money talked.

So, was the battle for women's toilets finally won?

Considerable opposition remained. None other than George Bernard Shaw, serving as a local councillor in Camden at the turn of the century, would recount how his fellow vestrymen mocked the idea of setting up a female public convenience. One claimed that local flower-girls would simply use it to wash their goods (i.e. the poor did not understand or need such things); another that any woman using a public convenience had "unsexed herself" (again, the question of female "modesty"). In the early 1900s, one lady public health worker noted her sister's reaction to her establishing a public restroom as part of her duties: "[she] turned away with disgust and called my work 'indecent.'" Women, moreover, remained wary of male mockery and attention when visiting public conveniences, often situated on prominent street corners. An anonymous 1890s correspondent in The Times claimed that many still used "retired streets" rather than face the gaze and remarks of loitering males.

This inhibition had unfortunate and lasting consequences. Statistics showed that women made less use than men of public facilities; and this, in turn, led sanitary engineers to prioritize space on their plans for men. Thus, the "selfish inequality" identified by the Ladies Sanitary Association would persist even into the present century. True, nowadays females may be less delicate about their need for public restrooms. Nonetheless, the long lines of women outside modern "objectionable contrivances" in public spaces -- where urinals are still often prioritized by architects and planners -- are a peculiar Victorian legacy.

Lee Jackson is the author of Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth.

___________________

Also on The Huffington Post: