Photos courtesy of kevinberne.com.

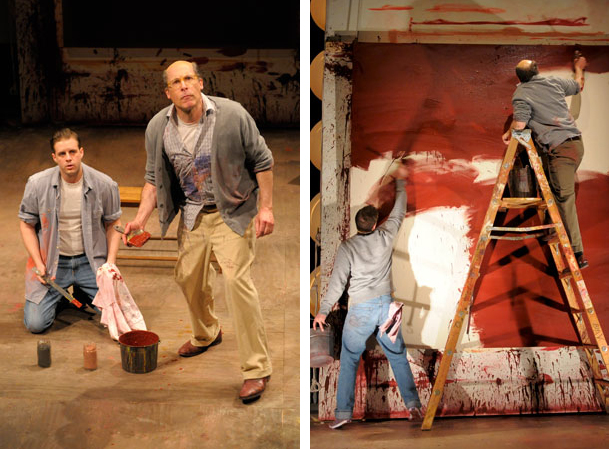

David Chandler as Rothko, John Brummer as Ken: contemplating and working

"What do you see?"

The question is the first line in John Logan's Red, a highly fictionalized portrait of the artist Mark Rothko, which is receiving a riveting production at Berkeley Rep.

Directing the words at a young man who has just walked into his studio, Rothko allows no chance for an immediate answer. Instead, he blurts a series of prompts about how the painting hanging before them should be perceived: about how far the viewer should stand from the canvas, the mindset that the viewer should bring to this specific work, the psyche that any viewer must possess to appreciate Rothko's thoughtful yet passionate art.

The young man's hesitant reply is unsatisfactory -- no surprise -- and provokes yet another rant, this time focusing on failings of society, differences between generations, and the struggles and triumphs of great artists. He names a few, among them Rembrandt, Matisse and, of course, Rothko.

Whether he merits inclusion in such company is doubtful. But there is no question that Rothko was one of the towering figures in the movement known as abstract expressionism, which raised American painting to the pinnacle of western art in the 1950s and '60s.

He was also the kind of artist whose biography provides the grist for high drama, having struggled with personal and artistic torments throughout his adult life -- two failed marriages, horrible relationships with his children, rage at dealers and critics and even at the people who bought his works -- before committing suicide at the age of 66. His final act was to slash his own arms; his blood-drenched body was found by an assistant, an event gratuitously foreshadowed in Red, which takes place a dozen years earlier.

Those qualities seem made-to-order for a skillful dramatist to exploit, and there is no question that Logan is a skillful dramatist. He is best known for screenplays, among them Hugo, The Aviator, Gladiator and Sweeney Todd.

But it is puzzling that Logan chose to focus his drama around a single incident, whose details are open to debate, rather than probe more deeply into the psyche of a deeply flawed genius. I say this while acknowledging that Red is as powerful an exploration of the mind and methods of an artist as we're likely to see on stage, and note that its 2010 Broadway production brought Logan a host of "best play" awards, including the Tony.

The pivotal incident surrounds a series of murals that Rothko agreed to paint for the Four Seasons Restaurant in the newly constructed and highly admired Seagram Building on New York's Park Avenue. Although he was consistently cynical about the ties between commerce, wealth and art, Rothko could not resist the $35,000 commission. In 1958, that figure was immense.

Logan uses the new assistant, named Ken, to bring the ethical contradiction into focus early in the play, then lets it lie until a climactic scene that is steeped in melodrama and a conclusion that seems far too pat.

The problem with the Four Seasons commission was not the money. It was the predictable conflict between Rothko's convictions, his visual style and the restaurant's atmosphere.

He abhorred the "likeable" in art and most everything else. "Where's the discernment... significance," he asks Ken, rhetorically. He approached the act of painting with agonized intensity and expected viewers to treat it with seriousness.

©1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society, New York

Mark Rothko, No. 301 (Red and Blue Over Red), 1959

His mature paintings -- after 1949 -- floated rectangular blocks of color above rectangles of another hue, sometimes in sharp contrast, sometimes barely separable, always shimmering. They were totally abstract, but in Rothko's mind they spoke in some undefinable way that overcame the barriers of time and place and culture to communicate universal truths.

In brisk scene after scene, Logan's text and actors David Chandler (Rothko) and John Brummer (Ken) reveal the intensity of the artist's convictions as well the sometimes-frenetic techniques that he brought to his work. The most dizzying two minutes find the men priming a huge canvas, using broad house-painter's brushes and keeping pace with a wildly exuberant piece of classical music, splattering each other's faces and clothing and finishing in total exhaustion. It's almost exhausting to watch.

Despite Rothko's declaration that he is not Ken's teacher, rabbi or father, their relationship evolves to the point where Ken feels free to challenge the older man's assertions with ferocity. They don't quite reach a father-son bond, but they come close, and they make us care.

Les Waters's direction presents the men and events in life-sized scale, in contrast to the larger-than-life approach of the Broadway production, and Louisa Thompson's paint-spattered set carries audiences into the authentic studio of a vigorously working painter. It's a work of theatrical art.

"Red" runs through April 29 in Berkeley Rep's Thrust Stage, 2025 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets cost $17-$85, from (510) 647-2949 or www.berkeleyrep.org.