I went to see Woman in Gold because I'm a Helen Mirren fan and have admired the Gustav Klimt painting at its heart since college, but wasn't aware that it had been widely panned by critics until fellow Second Generation writer Helen Epstein deplored the reviews this past week.

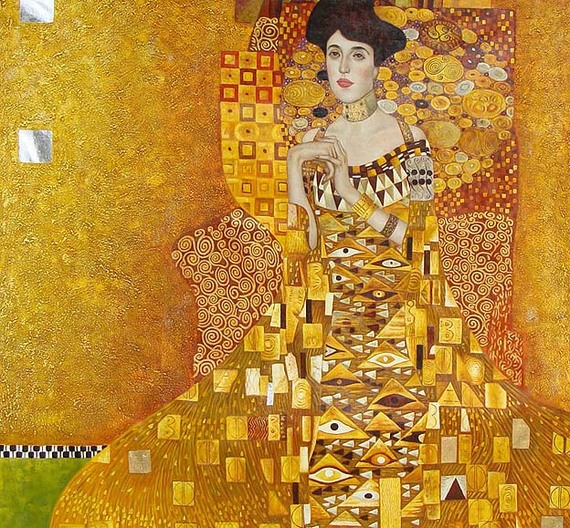

For those who don't know the story the film tells, it revolves around an Austrian Jewish woman living in America who's trying to get back Gustav Klimt paintings stolen from her family by the Nazis, decades after the Holocaust. But these aren't just valuable family heirlooms, one of them is world-famous and a portrait of her beloved aunt that the Austrians think of as their Mona Lisa:

(Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, Neue Galerie New York)

I was gripped by the movie from the very beginning. Helen Mirren's flinty exterior reminded me of German and Austrian Jews I grew up around in Washington Heights (or met elsewhere in New York) and her accent sounded perfect to my ear. Her fussiness, her occasional lack of tact also seemed just right.

The sad sack lawyer taking her case is played by Ryan Reynolds and he seemed an ideal foil. He's failed in his own private practice, but he's not just any lawyer, he's the grandson of a famous Austrian Jewish composer Arnold Schoenberg and so his journey through the film is almost as fascinating as Mirren's. The change in him is subtle but powerful and he does a great job playing against type.

The New York Times review cluelessly complained that the movie gave viewers "a standard historical drama about good guys versus bad guys. The bad guys are modern-day Austrians, portrayed as cold, arrogant enemies of truth and justice.....The good guys are Holocaust refugees and their American descendants, who take Maria's case all the way to the United States Supreme Court."

But there's nothing standard about this story, and nothing exactly like it has been told before on film. Reports by Austrians themselves substantiate the continued struggle to restore looted works of art to their original owners despite the obvious justice of their claims. Are the people blocking these attempts supposed to be shown sympathetically? The quiet obduracy and cruelty of the Austrians in this film was what you'd expect of any powerful bureaucracy trying to thwart an individual--and historically accurate in this case.

Even more wrong-headed than the Times was a sneering Variety review that said the movie, with just two exceptions, "present[ed] all Austrians as cardboard villains -- cruel, greedy and staunchly unhelpful" when this is patently untrue and sounds more like propaganda than a review. It also found the representation of Austria's wartime anti-Semitism melodramatic. What was the film supposed to do, give us The Sound of Music with some paintings thrown in? Or maybe The Producers was more to the reviewer's taste, and real emotion and history hard to stomach?

Perhaps I missed something, and April was declared "Be Nice to Austria Month" when I wasn't paying attention.

Both reviews I've quoted were typical. Overall, the critics seem to have had an agenda because their reviews reek of disappointment. I went with curiosity, but I honestly did not expect to be moved, having seen dozens of movies and documentaries about the Holocaust and read hundreds of books about it. And yet I was deeply touched more than once. Reynolds, though playing a Jewish character with Viennese roots, was a kind of Everyman until one crucial and powerful epiphany that reviewers dismissed.

The movie skillfully weaves powerful and elegiac flashbacks to pre-Nazi and occupied Vienna into its narrative so that the storytelling is never simple, but multi-dimensional. And always, Woman in Gold draws a sharp contrast between the glitter of a lost world represented by the painting, its gold leaf, and the magnificent diamond choker worn by the subject, and the everyday life of the people in both countries brought together by the fight over its ownership.

Having been deeply hesitant myself about traveling to Germany on the first of several book tours, I was caught up in Helen Mirren's anguish about returning to the Austria that had mistreated her, murdered her family, and looted her home. Her journey is ultimately a profile in courage in a movie that I hope people will connect with despite so many critics' sour, contemptuous, and uncomprehending reviews.

Lev Raphael is the author of the novel The German Money, which The Washington Post compared to Kafka, Philip Roth and John le Carré--and 24 other books in genres from memoir to mystery.